Before leaving Washington this April for a trip home to Louisville, Kentucky, I made a stop at the Supreme Court. It was just after dawn on the last Sunday of the month, and I parked along the south side of the building, on Capitol Street, and strolled around to the front where I stood at the foot of the grand staircase leading up to the eight columns seen on so many postcards. I wanted to visit the court before leaving because I knew that part of what I was looking for in my hometown was supposed to be located here. In two days, lawyers would make the case to the justices and the country that gay people should be afforded equal treatment under federal law and be allowed to legally marry one another. Included among the cases consolidated for the court’s consideration was Bourke v. Beshear, in which four gay couples in Louisville, legally married elsewhere, sued to have their unions recognized by the state. After one federal judge ruled in their favor, the decision was overturned on appeal, and gay marriage remains illegal in Kentucky pending the Supreme Court’s decision. For the United States as a society, and for me as a reporter and gay man, this was a momentous occasion; one I had waited a long time to witness, since 1992, when I got my first news job as a 21-year-old columnist and reporter at The Oldham Era, a weekly paper in rural Kentucky.

And yet I was content to be going away. A sense of unease had been growing in me in recent months as I watched homosexuality hurtle toward full acceptance. I knew that no matter how the justices ruled this summer, the fight over gay rights will continue. It’s been 51 years since the Civil Rights Act passed, and yet five minutes in Baltimore will tell you that the fight for racial justice persists. Roe v. Wade was handed down in 1973, but try to find a place to have an abortion in West Texas.

What’s more, the broader questions of what these transitions signify for gay culture, and for me, would not be satisfactorily posed or answered by the justices. For that I needed to look not forward, to the United States that will be shaped by the court’s decision, but backward to the time and place that shaped me, to Louisville, where I had learned, without ever having to be taught, to conceal my homosexuality. It would be a different environment altogether, one in which gay life was specific to its place, but also caught up in the same greater social and political undercurrents driving gay culture everywhere. The journey of gay life in San Francisco or New York is essential and powerful—but it is known, chronicled nearly to the point of a social progress fable. A smaller city with a gay history largely unexplored by the outside world would draw the changes into higher relief, and just about anywhere would do. But nowhere else would my allegiance and connection to the issues be as strong as in Louisville.

What I’d find there would be both familiar and new. I was an experienced reporter on gay rights in places like Dallas, San Francisco, and Washington D.C., not Louisville, the city that raised me as a closeted youth. I had never participated in that city’s gay life. My identity as a gay man didn’t develop in a meaningful way until well into my twenties, after I had moved away. Yet Louisville remained my home even if I no longer lived in it and might never do so again. The only way I could truly understand my role in American society as a gay person was by reckoning with the place that had created, and in a sense, exiled me.

Perhaps I was still reeling from the despair I had felt last spring after watching HBO’s adaptation of Larry Kramer’s 1985 autobiographical play The Normal Heart, which recounted the early years of the AIDS crisis. Without quite knowing why, the movie had provoked emotions in me about the pain and death the disease had introduced not just into the gay community in New York, where it was set, but also into my Louisville. I had turned the television off, shaken that such a tragedy had happened to people who were just like me, right next door, and it had barely penetrated my awareness.

Or maybe it was the way the gay neighborhoods that I had discovered with such relief in other cities after leaving Louisville, had begun to evince a monotonous sameness: more open but somehow less gay. A while back, I read that a local paper in Louisville had asked a gay owner about the club he had just opened in one of the trendiest parts of town. Gay bar, he said? We don’t use that word. “Why do you need a separate bar that says, ‘I’m this’ and ‘I’m this’?”

Why indeed? Acceptance, normalization, integration—an end to the dark rooms and drawn shades, the bookstores and backrooms and street-corner second glances: It’s what gay people in Louisville, and everywhere else, had been demanding for decades. Only a fool would want those days back, right?

Right. Still, something about those older times seemed to demand an act of remembrance even if I never wanted to live them again. I left the court and began the drive west toward Kentucky. I was headed for a Louisville that no longer existed, one in which older generations of gay men and women had lived and played and loved in secret; and one in which the victims of AIDS and ignorance and hate had died, too. My hope was that if I stood in the places where my predecessors had stood, I’d finally understand what had truly been at stake all these years.

My childhood in Louisville in the 1970s was a good one, of a sort that seems to have disappeared in this country to such an extent that many people no longer believe it existed at all. I had two smart and loving parents, and four siblings whom I adored. Ours was a yes-sir, no-ma’am house; handshakes were firm, and bigotry and scorn of all kinds weren’t tolerated.

My father, who’s 86 now, traced the family lineage in Louisville to a Revolutionary War fighter who ended his days as the city’s first riverboat pilot, licensed by the state legislature to guide boats around the devilish Falls of the Ohio River. My father was a journeyman photoengraver, and for 45 years a member of the Graphic Communicators International Union. He led his local to strike three times. My mother came from a large Italian family from Ohio. She moved to Louisville after spending two years studying journalism at Ohio State. I got to know my Ohio relations on frequent trips north, and I have fond memories of red-sauce suppers on Sundays with the entire extended clan.

Even as I recount this idyllic upbringing, I know it’s only part of my story. The fuller narrative tells me that I was not a Lindenberger by birth, but adopted by these good people when I was four. It includes four years in foster homes before that, and visits, on occasion, from families thinking of adopting. They’d show up, with presents and smiles, and never come back. I include these facts here because they offer some context for the double life I led until my twenties. I never knew I was gay—not really—until I was in my late teens, and it would take until my mid-twenties before I’d begin to accept it, and share it. What I did know, from an early age, was that I felt closer to some boys than they’d ever feel about me. I didn’t know why, and I didn’t know what to do about it. When people ask me about my childhood, I tell them it was wonderful.

In 1988, I was 17 and a senior in high school when some classmates and I were rounded up to sit and listen to an alumnus who had returned from California to tell us about sex and death and AIDS. He spoke for about half an hour and left time for questions, though I don’t remember there being any. About AIDS, I knew nothing—and didn’t care to know more. The disease, though rarely discussed in any of our households, was strongly linked to homosexuality and for almost everyone, myself included, that meant it was a topic safe only as an expression of locker room anxieties or playground putdowns.

Dr. Mark W. Lambertus was 31 and looked young for a doctor, and as I think back on it now, handsome. He told us he was working with AIDS patients in San Francisco, and even I knew that was a city of gay people. But what Lambertus didn’t say, and none of us guessed, was that he was gay, too. This was less surprising, perhaps, given that our school taught the poetry of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson without reference to either’s sexuality. But it also never occurred to me to wonder if Lambertus was gay. I assumed he was a kind of do-gooder, a missionary working among those who needed saving.

He would be dead of AIDS before any of us gathered to listen to him that day had finished college. It had been years since I had thought of that day, and when I did finally did, the memory brought with it shame. Shame from the realization that his talk left such a shallow impression on me. Shame that the struggle that was his life, and death, passed right under my nose without so much as a twinge of self-awareness. I was vaguely aware of AIDS as a gay-related disease that had become dangerous for others, too. But like discussions about drugs and drinking—subjects with which of course my peers were much more closely connected—it passed gently across the surface of my mind: A warning, at best, left dormant until needed—or opportunity—triggered a response.

Looking back, maybe it’s no surprise that I knew so little. There was so much that I didn’t know then. Across the United States, homosexuals—and, increasingly, heterosexuals, too—were dying in large numbers from AIDS, but it didn’t register with me, not in any kind of way that left a mark.

By the end of 1988, 128 Kentuckians, including three teenagers, had died from the disease. The following year, when I entered college, AIDS had killed more Americans of Lambertus’s age than heart disease, homicide, or suicide. In 1992, the year of Lambertus’s death, 57 out of every 100,000 men between the ages of 25 and 44 died of AIDS, more than any other cause, including cancer and car crashes. The numbers kept growing. By 2001, AIDS had claimed the lives of nearly 500,000 Americans, including those of more than 5,000 children.

The things I didn’t know would fill many magazines such as this one. For instance, I hadn’t known that in 1986, when Paul Cameron, a former University of Louisville professor, came to town to give a talk about what the city should do to slow the spread of HIV, his first suggestion was that the police require residents to be tested for the virus when applying for marriage or driver’s licenses. Anyone who tested positive for the disease would be given a choice: Be quarantined in their homes, or be forced to wear a letter A on their clothes to alert anyone they might come in contact with.

When I shared this story with people back in Louisville this spring, many just shook their heads. The AIDS crisis changed the gay community in Louisville, like it probably did everywhere. Besides the obvious toll it took, it also pushed many people out of the closet, long before they were otherwise ready.

George Stinson, a prominent gay bar owner, told me he’d seen that first hand. “One of our bartenders was one of the first AIDS patients in Louisville,” he said. “I will never forget it. His name was Tim, and he didn’t show up for work one day. I got on the telephone and called. He says, ‘I am sorry I didn’t make it to work but I am really, really sick.’ I said, ‘What’s wrong with you, honey? Do you need anything?’ So I go to his apartment, and oh, he looked like hell.”

They got him up and to the emergency room. He was back with the doctors, and Stinson and his friend and business partner, Ed Lewis, were in the waiting room.

“We were there an hour, hour and a half, and these doctors came out and said, ‘Tell us about your friend. What’s his lifestyle? We talked to him and he was kind of evasive. But there is a disease we keep reading about and it’s called AIDS and it’s sexually transmitted. So we want to know if he is homosexual?’”

Rather than answer, Stinson went with the doctors back to Tim’s room. “‘They want to talk to you about your sexual orientation,’” he told him. “He says, ‘You mean that I am gay?’ Well, right then they started, I mean the emergency room cleared out, I mean fast. They moved him into an isolated room, and you had to put on all the garb to go see him, the gloves, the suit, everything.”

By the time Tim’s family arrived a few days later, it was clear he wasn’t going to survive. “They were very resentful,” Stinson said. “They got there, and his father said, ‘Are you Timmy’s boss? I said yeah. He says, ‘We’re out of here. It’s your problem now, not ours.’ Walking out of the room, one of the brothers said, ‘He’s just a queer.’”

Springtime in Louisville is as pretty and cheerful as anywhere in the United States. Especially at Kentucky Derby time when no kind of work seems especially urgent. It’s a cliché, but people’s minds really do turn to bourbon and horse racing and merrymaking. People like to blame this lax nature on the influence of New Orleans on the city, which dates to the early nineteenth century, when Robert Fulton’s steamboats turned the Ohio River into a water-borne toll road.

For most of the past 50 years, George Stinson has been an important part of the city’s cheerful disposition. Now 69, he’s one-half of Louisville’s most successful gay business partnership. He lives with his partner Eric Haner, an elected state judge, in a large house overlooking the river, with a whiskey heiress for a neighbor, and the governor’s personal phone number on his iPhone. Thirty years ago, he and Ed Lewis opened The Connection Complex, which at 30,000 square feet is today one of the largest gay dance clubs in the United States, complete with a 500-seat drag show theater, and enough space to give Lady Gaga a rousing welcome when she shared the stage with a shocked impersonator in 2011.

Stinson had invited me to one of his latest ventures, Marketplace Restaurant, on South Fourth just off Broadway in downtown. It was Kentucky Oaks day, the day before the Derby, and the city was crackling with pent-up excitement. Tables at the Marketplace had been booked solid for weeks, and gays from all over the Midwest had been planning their Derby Eve at The Connection for longer than that.

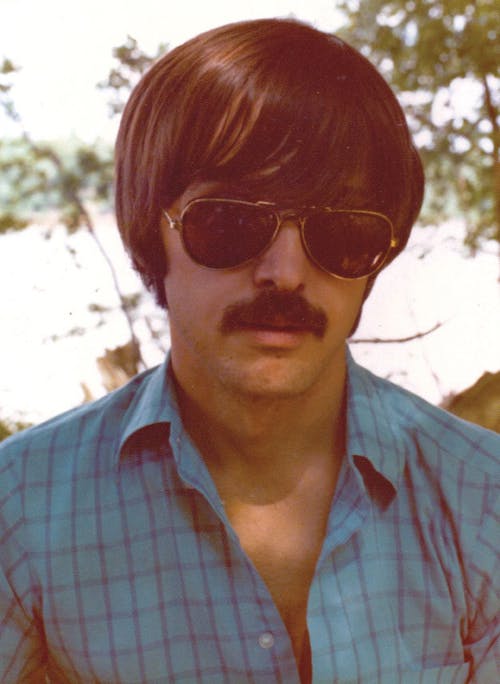

Stinson, dressed for Derby Week in expensive shades, a bright yellow shirt, and a crayon-bright orange bow tie, was telling me about the gay scene on South Fourth five decades ago, which he had discovered entirely by accident. It was 1965, the year after he graduated from high school, and Stinson was out for an evening with his cousin, also named George, and four friends. They were underage and looking for a place to drink.

Stinson began experimenting with his sexuality from a young age, but he wasn’t out, not even to himself. He told me about a friend he used to go on double dates with, and how the two of them would bide their time until the girls went off to the powder room, leaving the boys to enjoy themselves alone for a few minutes. “But if you had asked me, is that gay?” he said. “Absolutely not.”

The year after he graduated from high school, while at the University of Louisville, his aunt and uncle, who raised him, decided that if he was going to move out, it shouldn’t be too far. They gave him the family’s two-bedroom summer cottage on the river.

“My roommate and I—he was my lover but that wasn’t known—were going to take the house together. To everyone else, we were just roommates. But you know, I do remember when it came time for moving day, my uncle asked me in front of my aunt: ‘So which bedroom are you boys going to use?’ And my aunt, right away, said, ‘Well, both of them of course.’ But my uncle, he knew something. It just wasn’t spoken of.”

Walking south on Fourth Street, toward the Ohio River and Main Street, they spotted a sign up ahead, a block south on Chestnut: the downtowner. cocktails. “We saw this pack of people going straight into the door and we just squeezed right on through,” Stinson said. “There was this small cabaret room in the back, just packed in with people. This beautiful blond-headed lady on a small stage was playing the piano and singing. People were just having the greatest time.” A booth opened up, and the boys crammed into it, three on a side. “So here comes this waitress,” Stinson said. “My cousin George right away was giving me the nudge: ‘Get up, and let her sit down.’”

“‘Wellll,’ she says,” Stinson said, laying on an exaggerated Southern drawl. “‘Is it you boys first time here?’”

“‘Yeah, yeah, yeah.’”

“‘Let’s just get this playing field straight. You think I am a boy or a girl?’” The waitress pulled up her sweater, exposing a chest covered in hair.

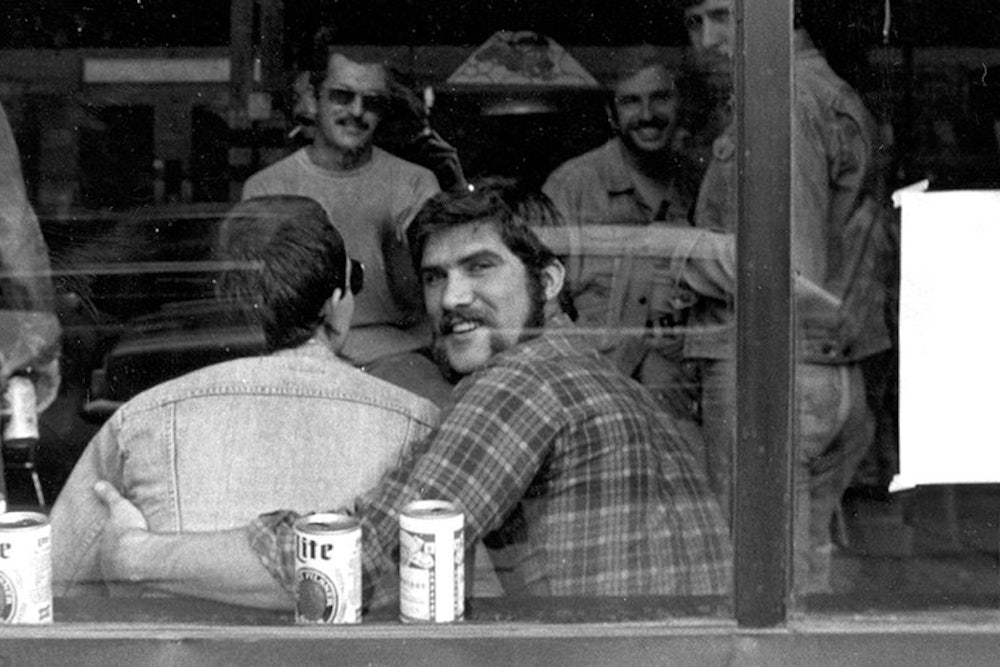

The boys had unwittingly wandered into what was for many years the only gay bar in Louisville. The Downtowner opened in 1953, after the Beaux Arts, a bar in the hotel of the Henry Clay Hotel at Third and Chestnut, which opened in the 1940s, became what’s widely considered the city’s first gay establishment. But the Beaux Arts and a similar place within the nearby Seelbach Hotel called the Beau Brummel, had been a place where men could meet discreetly and in relative safety. The Downtowner, with its waitstaff in drag and performers onstage, was something else altogether. Louisville also had gay pickup spots, including Cherokee Park in the east end, the oval in front of the Louisville Free Public Library, and Central Park, a half-dozen or so blocks to the south on Fourth Street. “It was either the bars or [the park],” David Williams, one of the editors of the gay newspaper The Letter, told me. “We had little groups—or families. I was the matriarch of one of the families. We’d go to the park and play volleyball and go home and have a potluck dinner. We took care of each other.”

Stinson ran away from The Downtowner with his friends that night, but eventually he came back. It was a couple of years later this time, and he was alone. Stinson was initially nervous among so many gay men all openly interacting in one place, until he noticed that one of the bartenders was a cousin of a boy from his high school.

“He looks up at me from behind the bar, and asked: ‘Are you gay?’” Stinson said. “I said, ‘Well, Dennis, I don’t think so. Can I stay if I am, or do I have to leave?’”

“He said, ‘You are welcome no matter who you are.’”

Stinson ended up working at The Downtowner, eventually becoming the manager of the drag business in the backroom. He left the bar in 1972, spending two years on the road managing a traveling drag-queen company. But when a fire destroyed The Downtowner in 1974, he returned to Louisville.

“I had saved enough money that I bought the name and the signage, and I called it The New Downtowner,” he told me. That was in July 1975. A year later, he met Ed Lewis, who performed as Eddie D, the drag queen, and Lewis bought out Stinson’s partners. They have been in business together for 45 years. (They became lovers, too, but split up after a couple decades.) By 1982, they had amassed a string of four small clubs but closed them all to open a place a few blocks to the east at Floyd and Market Streets. They called it The Connection.

It’s hard to put the history of gay Louisville into an exact chronological order, to situate it into a tidy narrative that goes from closeted to open, unjust to humane. It didn’t work that way. It was less of a timeline than a flow, akin to the waters of the Ohio River, with currents that speed up and slow, occasionally flowing backward, or veering off into unexpected tributaries.

Jack Kersey moved to Louisville in 1951, two years after leaving his Washington D.C., home at age 17 to move in with a dentist from Kentucky named Charles Gruenberger. The two had met at a gay house party, events that were common in the capital at the time. Kersey knew right away that Louisville was different from the relatively open environment for gays that he had experienced back home. “Just very conservative,” he said. “Everyone was very, very discreet.”

The couple remained in Louisville for only two years, but returned in 1953 and stayed for decades. When the AIDS crisis hit hardest in Louisville, Kersey was one of the founders of the Community Health Trust, and later provided the house that became an informal AIDS hospice for patients with no where else to turn.

“We were in Louisville for two years and then Charles was drafted,” Kersey said. The military sent him back to Washington because they needed a root canal specialist at the Pentagon. “Raised his rank from lieutenant to captain.”

Kersey returned to his life in Washington without regret, but he couldn’t live completely in the open. He had taken a position as a dancer with the Washington Ballet, and was surprised one day by investigators from the military who unexpectedly stopped by the apartment he shared with Gruenberger to clear him for his new assignment. “I was going to rehearsal, dressed in leotards,” Kersey said. “The investigators asked me several questions and I don’t think there was any question that we were a gay couple.”

Kersey knew things could have been a lot worse than a few questions. The Pentagon had begun broadly employing psychological screening to weed out gay draftees for the first time in the early ’40s. A corresponding pursuit of homosexuals serving in the federal government was now underway. Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare had given way to the Lavender Scare, which came to a head in 1953 when President Dwight Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, making homosexuality a disqualification for federal employment. Thousands were investigated and eventually fired.

Kersey figured that they were spared because of Gruenberger’s talents as a pioneer of root canal surgery. “We were pretty sure they didn’t do anything to us because they needed him with his specialty at the Pentagon,” Kersey said with perhaps some ironic amusement. Washington D.C. in this era was divided, with a public face that evinced an intense homophobia, one that seemed to have little connection to the thriving underground where men and women met easily.

“I always knew that I was gay,” Kersey told me. “I knew always you had to be careful about what you did and whom you did it with. My father told my brothers to beat me up to make me less feminine. That never worked, and they stopped when I learned how to fight back.”

Yet when Kersey left home as a teenager, he found a city full of opportunity. “During World War II and just after in D.C., there were five men to every woman,” Kersey said. “I was very active when I was away from school and home. The movies were cruise-y and so were the parks.”

Kersey also liked to cruise gay bars with suggestive names like the Chicken Hut. But being gay meant being on guard. “Living in the McCarthy times was very frightening for gay people,” he said. “We had a private party in our home when we heard a siren pass and stop close by. Several people climbed out the windows and ran out the doors for fear of a raid.”

The couple moved back to Louisville in 1953 when Gruenberger opened a private practice, and he joined the faculty at the University of Louisville. That bifurcated existence grew tighter, and their social lives became far more proscribed and private. Gay bars and meetups in upscale hotels were just coming on the scene. For men or women with jobs, or families, the risk of exposure was great. “Most of the socializing for gay people was done in the home,” he said.

It wasn’t until the 1960s when the couple vacationed in San Francisco that Kersey began to understand how far into the background gay lives had been pushed in Louisville. The gay clubs along Castro Street had big windows and open doors. “For the first time I saw what it meant to live out of the shadows,” he said. “I was used to Louisville, where the windows on the clubs were always blacked out.”

Like the Regal Queen, a drag bar in the historically black Smoketown section of Louisville, which was located in a dilapidated building that had previously housed a bordello. Or the Falls City Businessman’s Association, which was actually a lesbian bar. Or the private parties for gay men and women, where people would arrive in hetero couples, and then separate once everyone was inside and safe from prying eyes. Or the classified ads men used to place in The Courier-Journal—male roommate wanted, female roommate wanted—which were really solicitations for lovers.

It was an atmosphere of fear, and the resulting repression remained strong in Louisville for decades. Jack Kersey allowed himself to be interviewed on the local news and became the first gay man in Louisville to be publicly outed on television. It was 1978. “I was tired of people not knowing who I was,” he said. “I wanted to come out of the closet and be myself.”

The reaction to his interview took two forms, both of which surprised Kersey. Most straight people who knew him didn’t seem to care. But many of his gay friends no longer wanted anything to do with him. They were too scared that the straight people in their own lives would realize that they were gay if they were seen with Kersey. “This was very hurtful,” Kersey told me in an email.

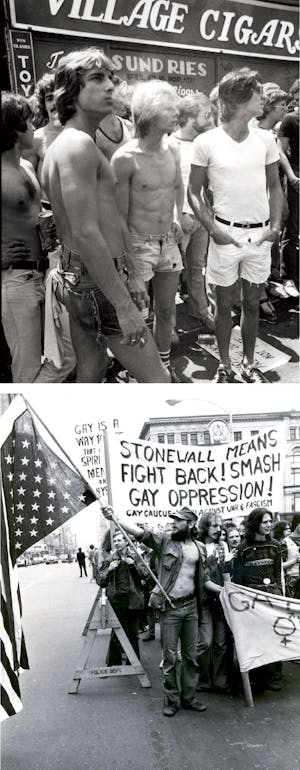

Kersey and his generation continued to stay mostly out of the public eye well into the 1970s, even as other people were emerging with entirely different sensibilities. When the drag queens in New York’s Greenwich Village began chucking rocks at the police outside the Stonewall Inn in the summer of 1969, Stinson, for example, was still entirely enmeshed in the underground gay world in Louisville. The significance of those days of anger in New York did not register with him at the time. “We were all aware of Stonewall, but it seemed like a tale told of a place far away.”

But for Micky Schickel Nelson, 1969 came at just the right time. She was 17 and was just about to graduate from a Catholic girls’ school whose campus was not far from The Downtowner. Coming out for Nelson was a simple matter: Her parents had caught her at age 13 making out with a neighborhood girl. “My father walked in and the only word I remember him saying is, ‘queers.’” After that, Nelson’s father told the girls that they had to stay in the kitchen and play cards. “So naturally, we just started hanging out at her house instead.”

All of which is to say that unlike Stinson and Kersey—and me—Micky Nelson knew who she was all along. “I think you have a harder time coming out as gay if you have a loving, supportive family,” she said. “If you grow up feeling you are going to lose the people you are closest to in life if you tell them, then you really don’t want to burn that bridge. But I didn’t have that fear.” Nelson’s parents were both older, and had both worked during her childhood, which was unusual at the time, she pointed out. “They really didn’t have any expectations for me at all, other than that I do well at school. So my support system were the people outside my family—my hippie-dippie friends and the people I ran around with.”

Rather than discover bars, Nelson discovered activism. Soon after the Stonewall riots, she read in an underground newspaper called The Louisville Free Press that the Gay Liberation Front, an activist group that coalesced in different cities after the Stonewall protest, was seeking to form a Louisville chapter. (They eventually started an informal community center in Louisville in 1971 and later started the city’s first gay newspaper—Trash.) She showed up with a girlfriend at one of the earliest meetings in 1970. It was held in a converted apartment in a run-down mansion in Old Louisville, a leafy, if sometimes sketchy, part of town where the city’s monied class had lived in the nineteenth century when steamboat traffic made Louisville one of the largest cities in the country.

“The first time I walked into a meeting I was surprised at what I found,” she said. “I just sort of expected, in my teenage narcissist way, that there’d be more denim-clad, radical people, people like me. Instead, there was this surprising cross-section.” She recalled one meeting where a heavy-set woman with bound breasts, cropped hair, and wearing a pair of Florsheim wingtips was accompanied by a very quiet, much smaller woman. At another, she said, “I remember someone asking me and my girlfriend, ‘So which one of you is the butch and which one of you is fem?’ and we just looked at each other and said, ‘If you can’t tell does it make any difference?’”

When the Gay Liberation Front decided it needed a larger space to operate from, one member rented a house in a Louisville neighborhood called the Highlands, east of Stinson’s restaurant and past Cave Hill Cemetery, where my mother is buried not far from Colonel Harland Sanders, the founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken. Cave Hill constitutes the northern border of the Highlands, a neighborhood that stretches southeast from the edge of downtown for three or four miles along Bardstown Road.

The house that the Gay Liberation Front rented still stands at 1919 Bonnycastle Road, a prosperous street dotted with old trees. The house has two floors and four bedrooms, one of which Nelson took, as well as a front porch and roomy common areas. The Front’s volunteers operated a telephone help line for gay people, and volunteers, friends, and all manner of strangers and hangers-on came and went freely.

One night in 1971, Nelson was getting ready to go to bed when she noticed a beefy man in a windbreaker coming up the stairs. “I had no idea who he was, but he didn’t look like he belonged.” It turned out he was a police detective, and within minutes nearly 30 people, residents and guests, were being subjected to a slur-filled lecture by the authorities. “I don’t know what had tipped them off, but they were ready for us that night,” Nelson told me. “There were paddy wagons outside, and they had enough room to haul all of us downtown.”

Nelson was bailed out quickly, and most of the charges against everyone were dropped—they related mostly to marijuana possession—but the names of the arrested were published in the newspaper, as people who lived in a gay house. Some lost their jobs, but Nelson got off easy. “I was working for McDonald’s. They didn’t care what I did, as long as I showed up.” Nelson was in the courtroom when two gay women tried to get married—one of the first documented cases in the country—and she began making appearances at local colleges to answer questions from students who were equally titillated and scandalized. By the 1980s, when the AIDS crisis began killing people, she and her partner, a lawyer, began to help the dying. “I witnessed a lot of wills,” she told me. “They were almost always alone. They just didn’t have anyone else.”

I arrived back in Washington late in the afternoon on Derby Day. The celebrations among straight people back in Louisville would have begun with the close of the race, in the city’s pedigreed restaurants and Bardstown Road’s bourbon bars. The gay bars in the Highlands—unafraid to keep their shades up—would be full as well. These are newer places, and they don’t always announce themselves as gay bars. In their modernity and openness, they present a different image of gayness than was once found in this city, one that differs greatly from that of their predecessors, establishments in which the ability not to be seen ranked among a place’s chief virtues. Stinson described it as a “gay format but without the gay identity,” adding that that was exactly what he and other gays had been fighting for all their lives.

I was also reminded of something David Williams told me. He said old bars and clubs were “like walking into a bubble. Once you walked out the door, well, you looked left and you looked right.” This might sound frightening, and it was, but it held a certain appeal for him, too. “It was like leaving a fantasy world, or leaving the cinemas. You leave the world of the movie behind, and you go home to your everyday life.”

But I was still preoccupied with the problem that had driven me, a week earlier, to the steps of the Supreme Court before I made the journey home. The importance of the gay marriage fight lies in its ability to force Americans to abandon the old hateful division of the world into straight and gay. I was confident, whatever the court decided, that the division would soon fade away. It won’t be missed. But even as we embrace this new and better world, an important question remains: What of the old one is worth saving?

There is still, of course, a gay Louisville. But it is no longer a separate culture exclusive to its members. I believe this kind of community does not depend on the self-defining strictures of prejudice and fear to exist. But to fashion a new gay culture, we must not let go entirely of the old one. We must continue to embrace the things that made us different and special, the sense of family and support—the unity of purpose—that stitched us together. That, finally, is what had drawn me home to Louisville: an act of commemoration, a final opportunity to pay respect to those who had gone before me. I will be happy when gay marriage is legal in Louisville, and everywhere. But there was a beauty, even in those uglier times, in the old ways, in the old Louisville.