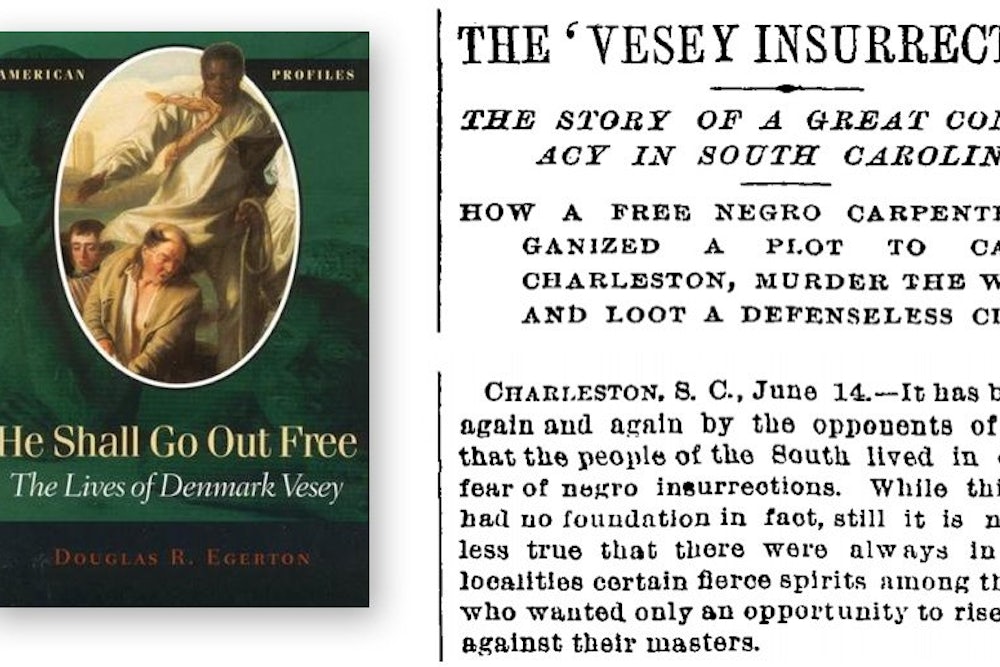

Denmark Vesey, a co-founder of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, where nine people were shot dead on Wednesday night, began life as a slave and died trying to free others. Vesey’s early life remains a mystery—he was born around 1767, likely in either St. Thomas or somewhere in Africa. As Douglas R. Egerton wrote in his 2000 biography, He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey, “Perhaps nothing speaks more eloquently about the dehumanizing nature of Atlantic slavery than the fact that one of the most influential abolitionists in antebellum America lacks a known birthplace and birthdate and, for approximately the first fourteen years of his life, even a name.”

The slave trader Captain Joseph Vesey recalled purchasing Denmark Vesey in 1781, and estimated later that Vesey was fourteen years old at the time. Vesey was brought to Cape Francis, where he lived for a short time with another owner, but was soon reclaimed by Captain Vesey when Vesey’s subsequent owner claimed the boy was suffering from epileptic fits. From then on, the captain kept Vesey with him on trading voyages, until he retired in Charleston in 1783.

By 1799, Vesey had acquired skills as carpenter and was married with children when he won a reported $1,500 in a local lottery, and purchased his own freedom. But his wife’s master refused to sell her to Vesey, so his family remained in slavery. With the remainder of his winnings, Vesey set up his own carpentry shop. Vesey’s shop prospered, and he quickly became a wealthy and influential member of Charleston’s black community. Vesey’s personal success is remarkable, but it’s possible that it actually came as a surprise to few at the time. In He Shall Go Out Free, Egerton writes that local “slave holders in later years regarded the boy as a person of ‘superior power of mind & the more dangerous for it.’” Many historical accounts of Vesey’s life mention his intelligence—and how obvious it was.

In 1817, following a dispute over burial ground with white members of Charleston’s Methodist Episcopal church (reportedly, white congregants built a ‘hearse house’ on black burial ground), some 1,400 black Christians formed a separate congregation, according to the National Park Service website on Charleston. A year earlier, the African Methodist Episcopal church denomination had been formally established in Philadelphia, and the church community in Charleston set up their church in that denomination in 1818. Free black man and church leader Morris Brown is widely credited as the founder of Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal church, but many cite Denmark Vesey as a co-founder, including the church’s website. Even before Vesey and his associates began discussing plans for an uprising, the church was seen as a threat to the white domination of Charleston. Within months of the church’s establishment, the Charleston city guard arrested 140 free men and slaves for worshipping in violation of city ordinances. Egerton theorized that Vesey might have been among them. In early 1821, Charleston’s city council warned against church leaders allowing African Church classes to become “schools for slaves.” By December of 1821, Vesey was plotting the slave uprising that would make him famous.

However, according to a June 1861 article on Vesey in The Atlantic, by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an official report from the time claimed that “[f]or several years before [Vesey] disclosed his intentions to any one, he appears to have been constantly and assiduously engaged in endeavoring to embitter the minds of the colored population against the white.” Higginson writes that scripture, in particular, played an important role in Vesey's rebellion:

“He rendered himself perfectly familiar with all those parts of the Scriptures which he thought he could pervert to his purpose; and would readily quote them, to prove that slavery was contrary to the laws of God, -- that slaves were bound to attempt their emancipation, however shocking and bloody might be the consequences, -- and that such efforts would not only be pleasing to the Almighty, but were absolutely enjoined and their success predicted in the Scriptures. His favorite texts, when he addressed those of his own color, were Zechariah xiv. 1-3, and Joshua, vi. 21; and in all his conversations he identified their situation with that of the Israelites.”

In an op-ed in The New York Times in 2014, Egerton describes a scene in which Vesey discussed the men who owned his wife and family with his fellow conspirators. “Vesey picked up a large snake in his path and crushed it with one hand. ‘That’s the way we would do them,’ he said calmly.” The plan was set for July 14, 1822. “They would slay their masters as they slept, fight their way toward the docks and hoist sail for the black republic of Haiti, where slaves had successfully overthrown the French colonists two decades earlier,” Egerton writes.

But in late May, everything came apart when one of Vesey’s recruits, William Paul, told a cook named Peter Prioleau about the planned exodus. Colonel John Prioleau, Peter’s master, was out of town when Peter first heard about the plan, but days later, on May 30, Peter told Colonel Prioleau, and the arrests of black men believed to be involved in the plot soon followed, as did hysteria among white Charleston residents. The local militia was ordered to patrol the streets. Vesey planned a second date for the uprising, June 16, but that failed as well, and within a week, Vesey was arrested. His trial began on June 26, lasted two days, and on July 2, 1822, Vesey was hanged with several of his co-conspirators. More than 100 men were put to trial over the uprising, and more than 30 were ultimately hanged. “In all, the two courts hanged more men than were executed in any other Southern slave conspiracy," according to He Shall Go Out Free.

Vesey’s story has long been a symbol of black resistance, but several prominent historians have challenged the leading theories on his life and death. In a 2002 article for The New York Times, author and journalist Dinitia Smith cites a journal article from the William and Mary Quarterly from November of 2001 in which historian Michael P. Johnson “argues that the original transcripts of the [trial] proceedings show that the African-Americans confessed to a conspiracy only after being beaten and tortured.” She continues:

“In the paper, Mr. Johnson writes that the coerced confessions in the case mirrored newspaper accounts and rumors in Charleston about the rebellion in Haiti in 1791, which had eventually led to the abolition of slavery there.”

The implication is that Vesey’s uprising may have been a conspiracy theory—not an actual conspiracy. Smith cites the conflicting opinions of several other leading historians, though it's worth noting that most historians do believe that Vesey conspired to lead the black residents of Charleston in an uprising and exodus. Smith concludes her article with a quote from Johnson that cuts through the debate, and gets at heart of the tragedy: “The truth on the scaffold was the integrity of the men executed for refusing to testify… and their ‘heresy’ at the time in believing in racial equality and the injustice of slavery.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Vesey's original plan for the uprising was June 14. He was planning it for July 14.