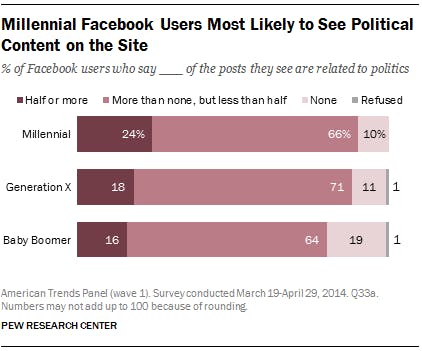

A recent report from Pew Research Center has pointed up a huge generational difference in the way people get their news: “Baby Boomers and Millennials demonstrate nearly inverse habits when it comes to local TV and Facebook.” (Sixty percent of boomers get political news from local TV and 39 percent get it from Facebook; those sources are basically inverted for Millennials.) While this has serious implications for media companies, it’s probably best to resist the claim that this shows a massive change in the way people think about the world, and what they actually want from news. Because while their formats are very different, the content of local TV and Facebook is the same: some real news, some political outrage, but mostly the same old stories about rich women misbehaving, brave pets, and horror stories from the police desk. The primary innovation of Facebook is that you no longer have to wait until 6:30p.m. for a heartwarming tale of an adorable child overcoming a terrible disease.

In The New York Review of Books, Michael Massing writes, "That digital technology is disrupting the business of journalism is beyond dispute. What’s striking is how little attention has been paid to the impact that technology has had on the actual practice of journalism." That might feel true but it’s not actually true. Every new communications technology has been the basis for claims that we’re approaching the end times for civil society. As Adrienne LaFrance and Robinson Meyer explained in The Atlantic in April, anxieties about BuzzFeed mirror what media people have thought about every new media innovation, from Time magazine almost 100 years ago to radio to cable television to USA Today to MTV. The secret to Time’s success, they wrote, should sound familiar:

Time turned boring newspaper reporting into fun blurbs. In other words, it aggregated. Its founders bet that its readers wanted to learn about the world but do it quickly, so it distilled local and world events into readable summaries shorter than 400 words. These story bursts were true stories, with a beginning, middle, and end, and their tone was relaxed but arch.

There has always been too much news. While researching another article, I came across an election dispatch in The Washington Post that concluded, “But one thing is finally, perfectly clear. The longest, most media-saturated presidential campaign in anyone's memory has, believe it or not, irrevocably come to and end.” The date is November 4, 1980 and CNN was only a few months old.

You can find the ancestors of social media-optimized BuzzFeed headlines deep in the archives of The New York Times. The lost dog comes home. (April 24, 1921: "LOST DOG WAR HERO FOUND. Irish, Blind and Shellshocked, Restored Through a Times Clipping.") The annoying rich woman trend piece. (December 27, 1880: "FRENCH SOCIETY. THE INTOLERABLE DULLNESS OF FORMAL EVENING GATHERINGS—THE VAPID TALK OF THE WOMEN.") Finding such examples is so easy that it kind of kills the fun. Search almost any term, and sort by oldest, and you can find an article that, with some edits to the language, could be at home on Elite Daily or Upworthy or whatever. Here's a story from July 7, 1884 that has all the Facebook-ready hyperbole and anthropomorphism of "15 Llamas Who Just Do Not Give A Damn": "THE PARROT'S LITTLE JOKE.; HE HIDES HIMSELF FROM HIS MISTRESS AND THROWS HER INTO A FIT OF ANGUISH." (A parrot who said obscenities briefly went missing. "With premeditated malice unequaled in natural history, the mottled pet had climbed up the lace curtains, crawled through the open window, and secreted himself on the cornice of the house. When tired of the joke he came in again and made the household happy.")

It turns out we’ve known that long headlines get more attention since way before Google Analytics. This Times headline from October 13, 1895, is about a popular listicle topic: “Our Colonial Ancestors Were Governed by a Stern Code. SMOKING WAS A HEINOUS CRIME History of Connecticut's Curious Laws — The Stocks, Whipping and Fines for Apparently Trivial Offenses.”

I recently attended an Intelligence Squared debate over whether “smart technology is making us dumb.” Those who argued that it was said we’re too distracted by our phones to think long and hard about serious issues, and also because something something selfies. But the Pew study finds that between the selfies, Millennials are actually reading more serious news that challenges their point of view. Millennials report seeing more political news posts on Facebook than older generations, and they're more likely to report seeing posts that do not support their views. Only 18 percent of Millennials say they always or most of the time see posts that support their politics.

The internet is not making us dumb. We were always dumb. Just like we make fun of old people watching Fox News now, in 30 years young people will make fun of old Millennials yelling at Facebook. The technology in this Simpsons joke will change, but the idea will be the same.