Milan Kundera has a strikingly capacious vision of the novel. In an interview with Philip Roth from 1980, he enumerated some of the elements of his fiction: “Ironic essay, novelistic narrative, autobiographical fragment, historic fact, flight of fancy.” The novel that made him famous, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is a meditation on philosophy, politics, and polyamory that employs all of these elements to narrate the intermingled stories of four lovers. The book even includes a printed excerpt from a musical score, Beethoven’s final string quartet, Opus 135. This abundance of forms allows him to make provocative and playful connections between seemingly disparate topics: political dictators and individual sexual taste, Nietzsche’s theory of history and Beethoven’s music.

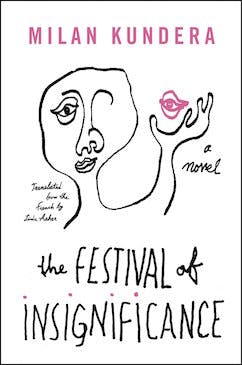

His latest novel, The Festival of Insignificance, shows a similarly heterogeneous profusion of modes. He muses in an essayistic vein on fashion, comedy, Hegel, and birthdays; he narrates his characters’ interactions in the parks and apartments of Paris; he inserts himself into the story (the characters refer to him as “our master”); and he makes Joseph Stalin a character, embroidering historical facts with fanciful speculation. The point of all this is to create what one character calls a “hymn to insignificance,” an ode to the ephemera of personal and political life.

Kundera’s novels have always occupied the borderlands between philosophy and literature. It’s revealing that his definition of a novel—“a long piece of synthetic prose based on play with invented characters”—also accommodates Plato’s early dialogues. He will often interrupt the flow of narrative with almost Socratic questions. “Why did he laugh?” Kundera pauses to ask in his new novel after telling us a character has begun to laugh. “Did he find his behavior comical?” His characters are constantly referencing European philosophy. One says, “You’ve never read Hegel? ... our master who invented us once made me study him. In his essay on the comical, Hegel says that true humor is inconceivable without an infinite good mood.” He is playfully explicit about the fact that as master and inventor of his characters he can make them converse about whatever he wants.

Fashioning an impish voice that questions cherished dogmas without letting that skepticism harden into dogma is an epistemic achievement as much as an aesthetic one. Kundera and his characters question everything, but they also question their own questioning. Certainty is a constantly receding mirage. Kundera’s belief that the wisdom of the novel “comes from having a question for everything” is prevalent in his fiction, both in the frequency of actual questions and the refusal to subscribe unambiguously to any conventional belief.

The Festival of Insignificance is an effort by an author in his mid-eighties, but the book resists the impulse to see only the somber or sentimental sides of aging. One older character gets excited by his insight that the birthdays of the elderly are in fact double events, simultaneous celebrations of “so-distant birth” and “so-near death.” The same character flirts with the proximity of death, spontaneously announcing to an acquaintance that he has cancer even though he has just learned he is perfectly healthy. Whatever his motive for fabricating an illness, the lie puts him in a good mood. And this adds luster to his imagined persona, “for cheerful banter makes a tragically ill man all the more appealing and admirable.” A perverse impulse makes him delight in donning the gravitas of the condition he has just escaped. Old age confers no automatic wisdom; the proximity of death is just another impetus for people to do strange, silly, and inexplicable things.

A particular species of gently comic paradox occurs throughout the entire novel. A man is fascinated by how cheerfully someone relates the painful story of the death of a mutual acquaintance. A woman is attracted by the boring and banal conversation of a serial seducer. Two people who seem to share no common language feel closer precisely because they have no way to communicate. Stalin sympathizes with the pain caused by a bureaucrat’s small bladder and renames a city in his honor. These are interesting and amusing ideas: Death can be a source of delight; dullness has erotic depths; incomprehension unites; and tyrants soften when they see the effects of a small and specific pain such as the need to urinate. But stated as bald propositions they lose the dynamic charm of Kundera’s novelistic inquiry; they are not positions he defends so much as possibilities he entertains for comic effect and intellectual stimulation.

The comic pathos of people failing to understand one another is a favorite theme of Kundera, one nicely expressed in his 1979 novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, where a couple enjoys “the perfect solidarity of perfect mutual misunderstanding.” In The Festival of Insignificance, an unemployed French actor named Caliban pretends to be Pakistani whenever he works as a server at private parties for the wealthy. He doesn’t speak a word of the language, but he communicates in studiously invented nonsense noises with a consistent grammar and syntax. The stunt is an absurd yet oddly poignant exaggeration of the subtle misunderstandings always latent in human relationships. The novel’s material traverses the same arc in opposite directions; Caliban’s lark begins in the spirit of play but gradually becomes a serious and melancholy isolation, while the old man who faces the formidable threat of cancer spins the specter into an elaborate private burlesque.

Despite the grandiose claims of the back cover, Kundera’s new novel is not “the culmination of his life’s work.” Like many late novels, it’s brief and diffuse, barely 115 pages. It’s more bagatelle than concerto, more ramble through the park than expedition to scale lofty peaks. But the novel makes its own drift towards triviality into a philosophical theme by asking us to think about the value of insignificance. What an older cultured French man named Alain thinks about the erotic value of the exposed female navel is not exactly a question of burning, universal interest. And if the entire novel devoted itself to portentous Parisian reflections on culture and sexuality, it would indeed feel like a bad parody of French new wave cinema. But a saving self-awareness punctures the pretensions of its philosophical musings. Kundera doesn’t present himself as a priest of the novel who, having been inducted into its higher mysteries, now deigns to share his brilliance with mere mortals. He is simply one character among others in the novel, curious, perplexed, and amused by the spectacle of human nature.