On Monday, 27 senators asked President Barack Obama to take executive action to ban federal agencies and contractors from asking about applicants’ criminal histories until later in the hiring process. Colloquially, the movement is known as “Ban the Box,” a phrase that was the rallying cry of formerly incarcerated organizers. The letter—whose signatories are all Democrats except for the independent presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders—reflects growing support for the campaign to reduce employment barriers for the estimated twelve to 14 million ex-offenders of working age.

Research has shown that those with past convictions are much less likely to get a callback—let alone a job—especially if they are African American. A disproportionate number of the more than two million people in U.S. prisons are African Americans, and criminal history questions have made obtaining gainful employment an enormous challenge. Given the growing support for Ban the Box the movement, a reasonable question to ask is: Does the policy work?

One way to measure the effectiveness of the Ban the Box movement would be to track the hiring rates for people with criminal records after the implementation of these policies. The available data is not robust, as many of these policies are new, but the numbers suggest that banning the box significantly helps. In Minneapolis, fewer than 6 percent of applicants whose background checks raised concerns were hired by the city prior to the 2006 decision to adopt a version of the policy. After its implementation, that number jumped to 57.4 percent. The city of Durham, North Carolina, passed a similar law in 2011; since then the proportion of people with records hired for municipal jobs has increased seven-fold, from 2.25 percent in 2011 to more than 15 percent in 2014, according the Southern Coalition for Social Justice (SCSJ).

“If you took the successes in Durham and were able to take that to scale across the country, you’d be able to offer a significant intervention to help the outcomes of people with records get employed,” Daryl Atkinson, a senior staff attorney at SCSJ, told me. He noted that none of the people with criminal records hired in Durham have been fired for illegal conduct, which points to another indicator—recidivism—of how well these laws function. A study, published last year in the American Journal of Criminal Justice, examined recidivism in ex-convicts who had been hired to government jobs in Hawaii, which stopped asking applicants about their convictions in 1998. The authors found that after the law’s implementation, a defendant prosecuted for a felony crime in Honolulu was “57 percent less likely to have a prior criminal conviction,” which they believe signified the law was “extremely successful in attenuating repeat felony offending.” Though preliminary in nature, it’s more evidence that suggests the policies are having their intended effect.

Devah Pager, a sociologist at Harvard University who has studied the effects of criminal records on employment, said that application rates would also be important to examine when assessing these laws. “There’s potentially a ‘chilling effect’ of criminal record screens that reduces job search by the formerly incarcerated,” she said. “Removing this screen may increase job search effort.” Another question: How well do those with criminal convictions fare once hired when it comes to retention and promotions? “There’s almost no research on this question,” Pager said.

While these studies are good at showing concrete effects of these policies, the Ban the Box movement should be seen as part of a larger effort to humanize those with prior convictions. “It’s a deeply stigmatized population,” said Michelle Rodriguez, a senior staff attorney at the National Employment Law Project (NELP). “The criminal record has been used to basically dehumanize a population and to treat them as less than deserving of human dignity and respect.”

The events in Ferguson and Baltimore—and the increased public attention paid to police killings of unarmed African Americans—have brought the problems of the U.S. criminal justice system to the fore. Rodriguez sees the progress of the Ban the Box movement as a tool for changing the conversation around ex-convicts. “I think it is incredibly relevant to the conversations we are having nationally about race and the criminalization of black and brown bodies today,” she said. Atkinson agrees. “This policy initiative is part of a larger movement which is really about removing the structural discrimination that people with records face in all aspects of life,” he said.

Like the struggle for LGBT and immigrant rights, Atkinson—who himself served 40 months for a first-time, nonviolent drug crime in the tough-on-crime 1990s—says those who have direct experience with the issue have spearheaded Ban the Box. He says the campaign “caught fire,” pointing to Monday’s letter to President Obama. “It highlights that movements and large cultural shifts are led by people most directly affected by the problem,” Atkinson said.

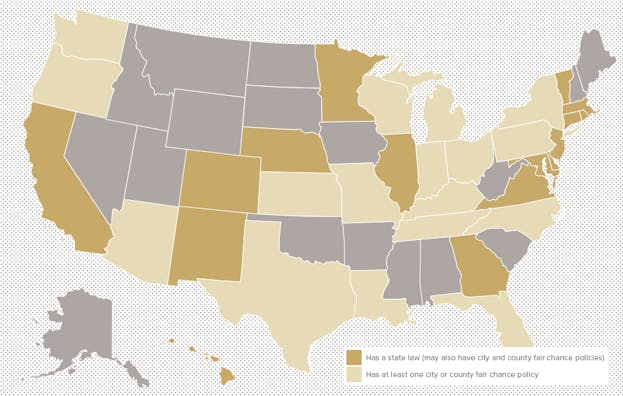

Ban the Box is certainly gaining momentum at the state and city level. According to NELP, more than 100 cities and counties nationwide have adopted such policies, as have 16 states. This year alone, Georgia, Vermont, and Virginia came on board. Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Rhode Island have gone a step further and removed conviction history questions from applications in the private sector as well.

Despite the lack of Republican signatories on the letter to the president, support for Ban the Box spans the ideological spectrum. Georgia’s Republican governor is responsible for his state’s ban, while companies like Koch Industries and Walmart have voluntarily removed criminal history questions from their job applications. Business groups complain that Ban the Box policies make the hiring process costly or time consuming, but Minneapolis found that their policy reduced the amount of time and resources necessary to process applicants for city jobs by 28 percent. What's more, it's estimated that the stigma against ex-offenders has cost the country tens of billions of dollars in lost economic output.

“Ban the box certainly isn’t a silver bullet,” Atkinson said. “But it presents a policy where a larger discussion can happen around the need to be able to offer access and opportunity to everyone in this country.”