In America, in 2015, large swaths of people with wildly differing political ideologies—and, in some cases, wildly differing factual and analytical premises—are converging on a series of assumptions they didn’t always share. The list is long, but it includes the following, timely opinions: that the drug war is a moral and practical failure; that three-strikes laws, mandatory minimum sentences, and myriad other aspects of our criminal justice system are flawed, racially biased, and in desperate need of reform; that the loosening of certain financial regulations in recent decades was disastrous; that the Iraq war never should have happened.

The political establishment hasn’t caught up to all of these consensuses, or emerging consensuses, but in most cases the public has, and in each instance the public has outpaced its elected officials. And when you view the aforementioned left-right convergence in light of federal policymaking over the past 20 or 30 years, it reflects poorly on our country’s most recent political leaders. Or at the very least, it suggests those political leaders made a number of very consequential decisions while they were in power without thinking past near-term politics. You might believe these errors stem from the inherent difficulties of governing, or from systemic institutional failures, or a mix of both. But the phenomenon is indisputable, and a reckoning with the causes is now inevitable.

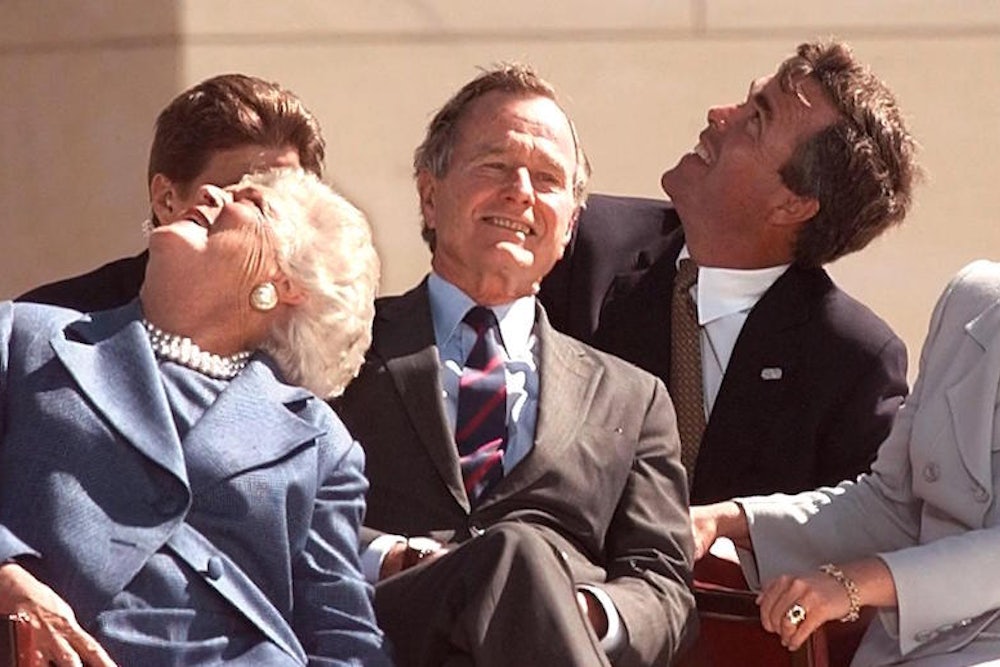

Why? Because these issues have moved to the foreground of the country’s political imagination just as the most recent president’s brother and his predecessor’s wife are running for president. In the absence of the Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush candidacies, a new paradigm could prevail without a great deal of bipartisan introspection. Instead, this election will force referenda on the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush presidencies. The coming Democratic and Republican primaries will to a great extent turn on how adeptly and convincingly Jeb and Hillary can explain away or atone for the country’s biggest public policy failures in recent memory. Were these mistakes? Were they rational decisions that simply didn’t withstand tests of time or have grown obsolete? Or, despite all appearances, is the jury still out?

From an elevated vantage point, the retrospective politics of the 2016 campaign should be easier for Hillary Clinton than for Jeb Bush to navigate. Whatever particular mistakes her husband made in office, the public generally remembers Bill Clinton’s presidency fondly, as a time of relative peace and economic growth. He left office popular and has grown more so ever since.

George W. Bush’s presidency, by contrast, is widely and correctly understood as a travesty—marred by debt-financed social policy, intelligence failures, the deadliest terrorist attack in U.S. history, grand-scale deception, a gruesome, losing war of aggression— which culminated in the country’s worst economic crisis in nearly a century. He became historically unpopular and has only returned to parity, or near-parity, by dint of the afterglow that tends to accrete around presidents after they leave political office.

And yet despite these fundamental differences, both Hillary Clinton and her husband are publicly grappling with the shortcomings of his substantive record, while Jeb Bush, if anything, is embracing his brother’s toxic record.

Jeb told funders in New York recently that when it comes to Middle East foreign policy, George is his lodestar. “If you want to know who I listen to for advice, it’s him.”

More damningly, Jeb told Fox News host Megan Kelly that he still supports the invasion of Iraq.

"Knowing what we know now, would you have authorized the invasion?" she asked.

"I would have," replied.

Jeb’s full answer was actually more ambiguous than most political writers, including Washington Examiner’s conservative reporter Byron York, are allowing. Though he appeared to suggest that the Iraq war was wise despite false pretenses, he added, “And so would have Hillary Clinton, just to remind everybody. And so would have almost everybody that was confronted with the intelligence they got.” But Jeb is painfully aware of the expectation that he’ll disavow George W.’s presidency. “[J]ust for the news flash to the world,” he told Kelly, “if they’re trying to find places where there’s big space between me and my brother, this might not be one of those.”

The Clintons are, by contrast, at pains to scrutinize their own records. Hillary's criminal justice speech last week, in which she called for an end to “the era of mass incarceration” was an implicit rebuke of her husband's former views and her own. Bill himself conceded that mass incarceration (and thus its attendant racial inequities) were partly attributable to a 1994 crime bill that he signed. Republicans, he said, insisted on incorporating the legislation’s tough-on-crime measures, but he was willing to accept them as the price of signing. “The problem is the way it was written and implemented,” Clinton told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour at the Clinton Global Initiative last week, “we cast too wide a net and we had too many people in prison. And we wound up... putting so many people in prison that there wasn't enough money left to educate them, train them for new jobs, and increase the chances when they came out so they could live productive lives.”

Hillary has had a more difficult time explaining how she landed on her belief that same-sex marriage is a constitutional right and explicating her position on free trade (which her husband supported unabashedly), but in both cases her current substantive views depart in obvious ways from her previous ones and thus constitute admissions that—at the very least—time hasn’t been kind to the Democratic orthodoxy of the 1990s, which she helped shape.

Though there’s a strangeness to the spectacle of Jeb embracing his unpopular brother while the Clintons break faith with their former selves, it’s also difficult to see how it could be any other way. Progressivism by its nature isn’t kind to old dogmas, which is why anyone who hopes to remain relevant in progressive politics for decades will eventually have to evolve and atone somehow. Conservatives are wary of precisely this kind of second-guessing. Republicans no longer zealously guard Iraq as a war of patriotic necessity, but they'll sooner admit that Obama isn’t a complete failure than that Iraq was a mistake on its own terms.

And here the dynastic differences between the Bushes and the Clintons further complicate matters. Unlike the Bushes, the Clintons don’t have a political ancestry. You can believe that they admit error now because they learn from their mistakes or simply because it’s the path of least resistance to power, but they aren’t the reflexive defenders of Bill’s every decision the way the Bush family must be of George W.’s.

That’s partly attributable to the unusually bad record George W. amassed over eight years—it’s ironically easier for the Clintons to admit select errors when they can defend Bill’s record in general. But it’s also partly attributable the fact that the Clintons just aren’t like the Bushes. As The New Republic’s Rebecca Traister wrote recently, “There are big differences between being born into a position of political privilege and marrying someone who becomes politically powerful.” One of those differences is that those in the latter category don’t have to treat the family name as if it’s a precious stone, in constant need of burnishment.

A further irony is that these apparently liabilities—the dynastic heritage, the conservative reluctance to second guess—each work to Bush’s advantage in Republican politics. But when conservatives fret that nominating a Bush will neutralize one of Hillary Clinton’s only big weaknesses, this—the inherent awkwardness of squaring the recent historical record with the current state of public opinion—is exactly what they have in mind.