A few weeks ago Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon was reported as declaring in private to a French diplomat that she wanted David Cameron and the Tories to win the 2015 U.K. general election. She denied this, not least because her supporters in Scotland like to think of her as a modern-day Mother Teresa and the SNP as a left-of-center party with the interests of the poor and downtrodden at heart. If indeed she was secretly wishing for a Tory victory, that would contradict the preferred message of this campaign.

Now, I don’t know if that story was true or not, but one thing is for sure—another Conservative-led government at Westminster is meat and drink for the Scottish nationalists. Not only have they achieved what is in effect a one-party state in Scotland, thanks to the utter incompetence of the Labour Party both north and south of the border, the SNP now has in a triumphant Conservative Party a bogey man to pick a five-year-long fight with in Westminster.

The narrative of Scotland as the victim of a Westminster conspiracy determined to do the Scots down is renewed, with knobs on. No matter that in the short term all the evils of Cameron’s first coalition government will be amplified and intensified, with the Scottish people paying the price just as much as the English, Welsh, and Northern Irish for Labour’s failure; if this outcome drives a wedge further into the Union, and makes a future referendum vote for independence more likely, the nationalists will deem it to have been worth the cost in food banks, welfare and benefit cuts and all else that now follows from another Cameron-led government.

Pincer movement dooms Labour

It used to be common political wisdom that Labour government in the U.K. depended on the Scots, where Labour for decades commanded a once-unassailable majority of Westminster seats. Without that block of solid red north of the border, it has long been assumed that the Tories were likely to dominate Westminster in perpetuity. And here we are.

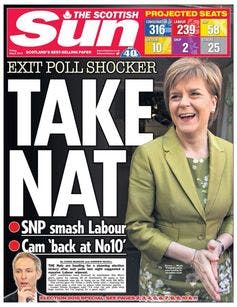

Rupert Murdoch appears to have understood this, urging The Sun to support the SNP in Scotland and the Tories in England. On this issue Murdoch and the Nats have long been on the same side.

Whether Murdoch really wants a break-up of the Union down the track remains to be seen, but he certainly has no problem with an SNP-led Scotland. There can be little doubt, based on Alex Salmond’s wooing of the News Corp CEO in the pre-phone hacking days and indeed right up to the referendumin September 2014 that the SNP would work with him to achieve that outcome, regardless of the consequences for ordinary Scots.

That would be a shame, in my humble opinion, but the people, and democracy, have spoken.

Scottish independence is not inevitable

Independence in the medium term is not an inevitable outcome of this election result, however. In the 2014 referendum, 45 percent of voters supported Yes and these are more or less the same 45 percent who voted for the SNP in the general election. As of this writing, the majority of Scots support neither the SNP nor independence.

The result is a mandate not for another referendum, therefore, but for devo-max—more autonomy, including fiscal autonomy, rather than less. That’s why Scots have voted for the SNP in such numbers this time, to prevent a rolling back of the commitments all the unionist parties made after the referendum.

Contrary to the propaganda of the nationalists for years, this would not necessarily benefit the Scottish economy in the short term. On the contrary, taxes may well have to rise for ordinary working people, to fund free NHS prescriptions, free student tuition and all the other benefits enjoyed by Scotland at present, and for which this vote is an endorsement. Austerity will become more important in a fiscally autonomous Scotland, not less, unless taxes rise significantly to pay for what is one of the largest welfare states in Europe.

And when the Scots see the impact on their own incomes and public services of breaking away from the pooled resources of the U.K., such as giving up the advantages delivered by the Barnett formula, the economic arguments for independence will begin to look problematic.

True nationalists don’t care about this, because their goal is full statehood, for better or worse. Their politics are tribal, spiritual, though certainly honorable. But they are not inherently left-wing. Historically, they have tended to the right.

Many who have supported independence and the SNP for what they perceive to be arguments around social justice and political direction are unaware of or unconcerned by this history. And they have been sheltered from the harsh reality of full fiscal autonomy thus far. Five years of full fiscal autonomy for the Scots could be just what the Union needs to inject a note of accountability and realism into the debate.

One thing is for sure. Scottish politics will be dominated for the next five years, as it has been for the last ten, by the constitutional debate. The Labour Party in Scotland seems helpless to prevent this, indeed hopeless overall, and the Tories seem ready to let the Scots go if it means preserving their majority in the U.K.

With English nationalism on the rise, fuelled by the anti-Englishness of the jocks in the north, it could all get very nasty.

This article was first appeared in The Conversation. Read the original here.