“I can tell you stories that will make your head spin, all day,” former NYPD officer Michael Dowd said. “One guy got shot in the head and still had a cigarette in his mouth,” he continued, by way of example. Dowd is getting his 15 seconds of fame right now for being one of New York’s crookedest cops in the late 1980s and early 1990s. A documentary about his exploits opens this Friday at IFC, titled The Seven Five after the East New York precinct Dowd policed and pillaged.

If you asked someone from central casting for a blue-collar cop who’s always cracking jokes, they’d be hard pressed to find someone better than Dowd. He’s a perfect fit for the big screen; and, in addition to this documentary, his story is en route to becoming a Hollywood movie. When I ask him about it, he quips, “What, you want a part in it?”

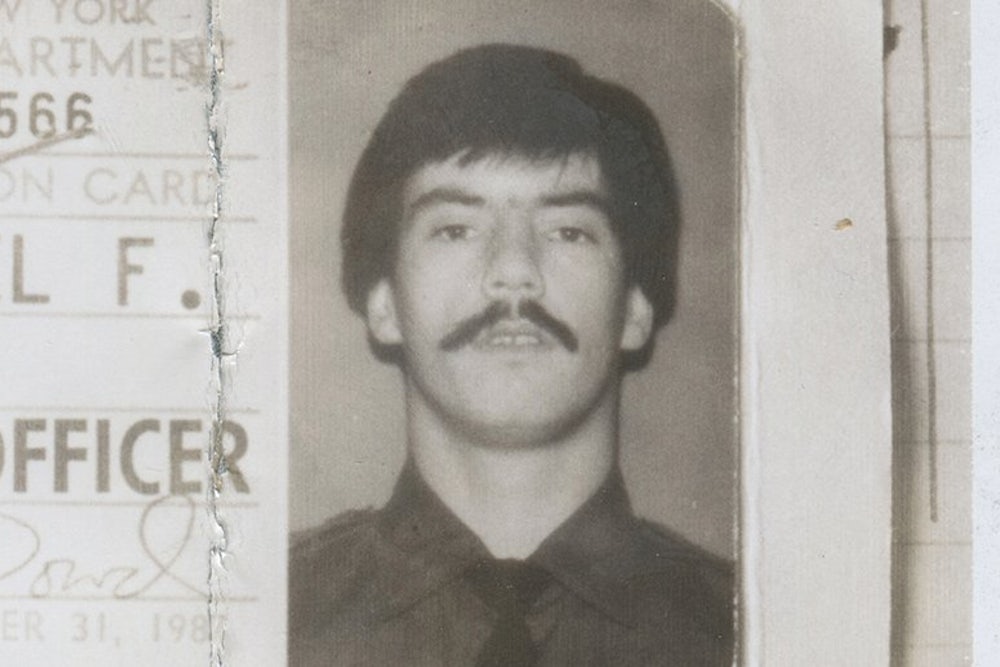

Dowd’s thick eyebrows are constantly moving up and down on his forehead, and he smirks when tells you about all the laws he flagrantly broke. “I did twelve-and-a-half years in prison. Can I laugh? Do I have to be remorseful forever?” He defends himself even before there’s an accusation that he might not be repentant enough. When you google Dowd, the first image that comes up is one from him answering questions during the Mollen Commission, a 1992 investigation into city-wide corruption in the police department. In the picture, Dowd is quite literally talking out the side of his mouth. That year, The New York Times reported: “a special mayoral panel asserted yesterday that the New York City Police Department failed at every level to uproot corruption and had instead tolerated a culture that fostered misconduct and concealed lawlessness by police officers.”

The Seven Five’s director, Tiller Russell, explained to me that the impetus to make the film came from the producer Eli Holzman’s interest in the Mollen Commission. When Russell came on board the project, his first job was to start tracking down former cops that might be willing to be in a documentary. Russell found Dowd.

“It was one of those weird drug dealer-type meetings,” Russell said, describing his first time meeting Dowd after tracking him down. “I got on the Long Island Expressway, got off, got back on so he could control the situation, make sure I was who I said, make sure no one was following us.” Right away Russell knew he had someone to build a film around. “Within five minutes of getting in the car with him,” he says, “I was like ‘this guy is a stone-cold fucking maniac but there’s definitely a film here and this guy is definitely a charismatic star.’ Whatever the morality of it, he lived through an extremely insane experience and he’s willing to be shockingly candid about it,” said Russell.

His film illustrates how Dowd’s exploits started—pocketing cash or drugs instead of vouchering them—and how they escalated. Eventually Dowd was burglarizing homes and businesses he knew had drugs and cash; for a weekly rate, he began selling protection to a local kingpin, Adam Diaz, to protect his business and give tips about raids. Dowd even bought cocaine from Diaz and sold it in his own Long Island neighborhood.

The Seven Five teeters between Dowd’s morality tale, and a sober illustration of the systemic issues in police departments that allow cops to abuse their power. “Yes this is a 1990s localized Brooklyn story, but hopefully it speaks to the sort of conflict and nuances and circumstances that leads to what we’re seeing across the country in different places in one way or another,” said Russell, referring to the recent examples of police abuse and brutality that have made the news. “[Policing] is in the zeitgeist because of a number of incidents that have happened and I think this film is a glimpse into the origins of what this controversy is.”

While Russell seems to think the film can add to today’s national conversation, Dowd is concerned about the timing of the film. “Why now? Couldn’t they have waited a bit? I feel like an emissary for the police,” he said, half-jokingly. Still, he gives frank insight into the experience of being one of the boys in blue where a no-snitch culture persists between officers and superiors. “You feel like you’re God, like no one can touch you,” Dowd told me. “It’s not the gun and the badge. It’s the test of the streets," he continued. "Their life depends on you, and yours on them. If you’re telling on me behind my back (and you always find out) I might leave you on the side of the street when you have a problem.” Dowd may not want his experiences to be extrapolated but when he speaks candidly about them, he illustrates the way power can be abused and provides insight into how a lack of accountability can linger. Both of these elements are at the root of how police are literally getting away with murder today.

Though in many places Dowd’s story of being a gangster-cop overrides the systemic critique Russell strives to make, the film does hint at the class nuances that precipitate corruption. The film illustrates the white working-class environment that policemen like Dowd come from. “My whole family was cops and firemen. The whole block was. The whole neighborhood was,” said Dowd. “We weren’t from the privileged class. I had seven kids in my family. Food was tough.” The reality is then cops, like Dowd, are placed arbitrarily at different precincts, where they have different degrees of privilege relative to the communities they are policing. Corruption tends to flourish in underprivileged neighborhoods.

Police departments are funded, in part, by property taxes—which means you’re paying cops the least in the neighborhoods where they can get away with the most, where the people they are policing have the least voice to stand up against them. “Greed plays into every decision,” Dowd told me. Unfortunately the systematic way certain communities are harmed by corruption and an organizational lack of accountability is only an aside in the film, a passing comment made by one internal affairs investigator. He mentioned that, as a consequence of Dowd’s corruption, the drugs and crime that police were supposed to be keeping out ravaged East New York. Save for the drug dealer that employed Dowd and the owner of an autobody shop that introduced them, no one from the neighborhood was in the documentary. Instead, the only traces of the people who may have been affected were the frozen-in-time faces we see in the archival black and white street photography littered through the film.

I saw The Seven-Five at a press screening at the SVA Theatre. During the Q&A, one question was asked twice. “Who do you want to play you in the movie version of the story?” Dowd answered the same both times: “Mark Wahlberg, Ryan Gosling, or James Franco.” Sony has already bought the remake rights to adapt the story into a narrative feature. It’s not hard to imagine the how the Hollywood version will play out: a story about a white cop tortured between right and wrong, good and evil, Wahlberg on the movie poster with an anguished look on his face, maybe surrounded by a few people of color and some graffiti in the distance. It’s much easier to imagine this movie in theaters than one about Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, or Trayvon Martin.