Duke University, where I graduated in 2002, was as lenient about student infractions—underage drinking, excessive noise, hazing—as most private universities. But there was a limit to its paternal forgiveness: on-campus interviews with company representatives. Miss one, and you'd have to go through a humiliating rigmarole of apologies and counseling. Miss a second one, and you were barred for life from interviewing on campus.

But the investment banks, hedge funds, consulting firms, and other big name employers on campus didn't have to play by those rules. They showed up late or not at all to company presentations, promised jobs that weren't coming, and didn't even bother telling applicants they'd interviewed that they weren't hiring you.

The hierarchy was clear and so was the message: The corporation is king. Duke would teach you all sorts of things, many of them quite leftist, but when it came down to it you couldn’t disrespect the harsh economics that keep a modern university going. As the career center puts it, not playing by the rules is “unprofessional and jeopardizes Duke's reputation in the employment community as well as your own.”

Duke is a business, as are all colleges, and everyone has their job. The professors cared more about their real job (publishing in academic journals) than teaching. The administrators were corporate types who spent most of their time fundraising. The overwhelmingly white fraternities maintained their privileged treatment (which included getting the best housing on campus) with meaningless community service projects. The students were taught, usually not very thoroughly and mostly by an overburdened set of graduate students and part-time instructors. But at least they got an easy curriculum and impressive résumé out of the bargain. And attached to it all was the basketball industrial complex, a multimillion dollar enterprise awkwardly selling itself as caring about the educational prospects of its athletes. It was a massive system built not around education, but status.

Some university presidents are remarkably candid about how they’ve transformed their institutions to serve market imperatives. Stephen Joel Trachtenberg, the former president of George Washington University, acknowledges that he worked to transform the school into a luxury brand. “College is like vodka, he liked to explain,” the New York Times reported in February. “Vodka is by definition a flavorless beverage. It all tastes the same. But people will spend $30 for a bottle of Absolut because of the brand.” The implication: All higher education is the same. Some schools are just cooler than others.

Framing college primarily in market terms must shape how students see the world. College is the first time most undergraduates are away from home, and so, in addition to whatever they learn in their coursework, students are learning how to navigate the real world of interests and priorities, of what you can get away with and what you can’t. Young adulthood may be the worst time to learn about morality. The pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for ethical decision-making, is still developing through your early twenties. You’re much more likely to go with the moral flow, signing up with Goldman Sachs or Bain Capital because everyone else is doing it.

More and more, thinkers are asking students to reject this impulse. William Deresiewicz, a former English professor at Yale, argued in an essay for The New Republic—and later in a book, Excellent Sheep—that students at elite colleges prefer status-seeking and resume-building to genuine intellectual inquiry.

Deresiewicz’s solution is for undergraduates at elite colleges to think more broadly about a meaningful life. He advises students to “invent your life” and “do what you love,” before acknowledging the difficulty of marrying one’s passion to a career. Elite colleges have increasingly been faulted for sending too many of their graduates to finance and consulting, and they’ve responded with this same solution: Drew Gilpin Faust, the president of Harvard, advised graduating seniors in 2008, “If you don’t try to do what you love—whether it is painting or biology or finance; if you don’t pursue what you think will be most meaningful, you will regret it.”

Trying to do what you love is a romantic notion that we shouldn’t believe will pan out for most people, as it contradicts economics and common sense. Why would a company have to pay you to do something you enjoy? We pay for things we like, and we get paid for things we don't like. But this idea that you should enjoy what you do burdens workers with guilt. The message is that if you don't find that magical unicorn, the beloved job, then you lack creativity and courage.

This is a preposterous way to think about our relationship with our jobs. Sure, there are a few creative types who can find careers they enjoy as musicians, actors, or even teachers. Faust advocates that only those with a passion for finance go into that field, but surely today’s economy demands more people staring at spreadsheets and profit margins than are truly passionate about those tasks. It's implausible in an economy with so many unemployed people (i.e., unable to find any job) that we should expect ourselves to find jobs we love and feel like failures when we don't.

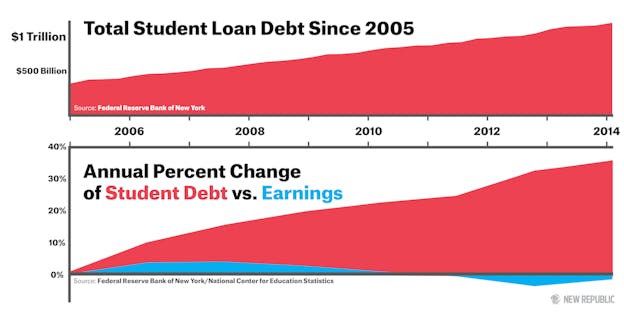

Americans typically decide where they’re going to college, and even which majors and careers they’ll pursue, at 17 years old, long before most people can be expected to know what they want to do with their lives or to even have a solid conception of who they are. Yet from that point forward they’re initiated into a system of debt, investment, and “human capital.” Questions like Who do I want to be? and What is the best use of my life? are warped by the question How am I going to pay this money back? By embracing the language and priorities of the market, elite universities make it more difficult for intelligent but impressionable students to see through the haze of money and economic success. So we can hardly blame students, as Deresiewicz does, for caring more about their careers than their education. This cannot be addressed at an individual level, by imploring teenagers to “do what you love.” Instead, we need to untether the university from the corporate world, and instead of blaming debt-ridden students for making financially motivated decisions, we need to see them as part of the larger problem of inequality. And we should even stop trying to convince every high schooler in America that college is the right choice for them.

There's a reason why an increasing number of graduates choose finance and consulting: These jobs pay more. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, management consultants earn an average of more than $90,000. Financial analysts earn an average of over $91,000. Registered nurses, on the other hand, earn less than $70,000. Elementary school teachers earn about $56,000. Even computer programmers earn only about $80,000 on average. The phony jobs simply pay more.

And they’re expanding. As important as biology should be to our changing planet, only about 100,000 Americans are employed as biologists. Yet our economy is demanding over half a million management consultants. Quite a few prominent billionaires lament the dearth of interest in STEM careers and usually suggest a PR campaign to make the jobs seem cool. The mystery is why this seems like such a mystery. Students are simply going where the jobs and money are.

The finance and consulting career paths are easier for another reason: They require far less commitment as an undergraduate. You can major in anything and go into those careers, but if you want to work in the sciences or engineering, you have to commit to harder majors and specific classes. When I was at Duke, the men and women who wanted to go into finance and consulting partied more, drank more, joined fraternities and sororities, and had a slogan for the hard-charging lifestyle they imagined after college: “Work hard, play hard.” The lawyers and bankers who dominate our world say the exact same thing. It’s basically another way of saying “careerism, consumerism.”

This corporate sphere of influence was much stronger than the opposing one: Elite colleges have a reputation for leftist thought. My experience at Duke was no exception. I once took a course called “Marxism and Society,” hardly the type of thing to convince you Duke was so obsessed with its corporate reputation. Yet leftist thinking is pushed aside in the life of the typical undergraduate. Three of the four most popular majors are economics, psychology, and public policy; these majors emphasize numbers-based thinking more easily transferred to finance and consulting. The burden of student loans discourages even upper-middle class students from pursuing majors that won't become careers. The more mainstream faculty endorses this approach. “The fall of the Soviet Union means no one thinks a system not based on the free market is viable anymore,” my first-year political science professor once told us, before deadpanning, “outside the Duke University English Department.” Everybody laughed.

My own career choice out of college was typical. I was an economics major with some interests but no great passion I could turn into a job, and a lot of student loan debt, so I went to work for a large corporation in a burgeoning sector of finance: credit cards. Some part of me must have known credit cards provide little of social value and take advantage of the poor, but another part of me must have known such objections wouldn’t get me anywhere. Whatever I learned in “Marxism and Society” disappeared when faced with the cold facts of paying rent and addressing my student loans.

Instead of asking students to shoulder the burden of improving society themselves through the dubious project of finding meaningful work, we should see that overwhelming student debt burdens have left students with little room to maneuver. Our debt-based education system reflects the neoliberal belief that college exists so its graduates will earn more: College is an “investment,” a crude financial term, rather than enrichment. We tell students to study what they find interesting and not what will make the most money, but we don't believe it. We still rank colleges by how much their students earn and expect students to pay back thousands in student loans no matter what happens to them financially. How’s that for do what you love?

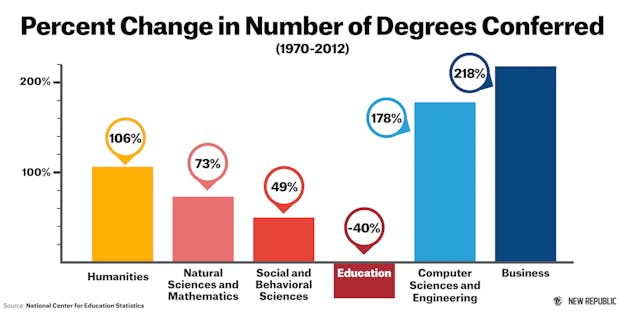

Some Republicans even accuse students and colleges of not being market-oriented enough. Senator Marco Rubio has proposed standardizing data on which majors at which colleges are likely to “yield the best return on investment.” Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin is trying to change the University of Wisconsin’s mission statement to include “meet[ing] the state’s workforce needs.” What’s particularly obnoxious about efforts to blame colleges and students for not doing what the market wants is how statistically incorrect they are. In the last 40 years, the number of undergraduate degrees conferred in all subjects has doubled. Humanities degrees have merely kept pace with that doubling, and social sciences degrees have increased by only half. But the number of degrees in business, engineering, and computer sciences has tripled.

Part of the reason colleges behave more like corporations is the burden politicians place on them to alleviate inequality. “It’s the chance to get a good education and a job that allows you to achieve financial security and retire comfortably,” Rubio says. President Obama said in December, “now, everybody understands some form of higher education is a necessity. And that’s a good thing.” Colleges are supposed to propel their graduates towards greater earnings power, and so they’re pressured to defer to the demands of the highest-paying companies. But not everyone can go to college, and there’s nothing wrong with wanting or having to do the low-wage jobs that still need doing. Pushing everyone towards college has become a convenient way to silence demands for addressing inequality more directly.

The neoliberal hope that education could be both a boon for our economy and a worthwhile investment for every student may be crumbling anyway. Larry Summers, an architect of the market-based reforms of President Clinton's era, has struck a refreshingly different tone recently, saying the jobs are simply not out there: “There are not three percent of the economy where there's any evidence of hyper wage inflation that would go with worker shortages. The idea that we just need to train people is an evasion of the problem.” But the idea that education is the universal solution to poverty and inequality still predominates. Charter schools often brag that 100 percent of their students go to college, never seeming to ask why college is necessary for everyone or what to do with people whose interests simply don’t align with attending college.

Pushing more and more people into our debt-based education system creates a destructive cycle, wherein more people go to college, creating higher college prices and more debt, and resulting in more people competing for the few jobs that can pay back that debt burden. In previous generations, the highest-paying jobs may have been in medicine or the sciences—jobs which increased the total economic pie—but increasingly these jobs are in finance, and the oversized financial sector has been shown to shrink economic growth and raise inequality. Thus, pushing people into education may make the situation worse.

Instead of pushing people towards college, we need to cut the link between debt and education for people who truly want to pursue higher education and directly re-distribute money to those destined for low-skill jobs. After all, there is still a tremendous amount of pre-tax inequality even in countries with better access to education than in the United States. Countries that provide free college tuition, like Germany and Sweden, have a level of inequality similar to the U.S. before income is redistributed though taxes and transfers.

The financial crisis confounded most neoliberal beliefs about how the world works, including the idea that making everything into an asset or investment would give us a smoothly functioning system. It should have provoked serious philosophical thought about our society’s value system, and the university should be the philosophical thought center of society. But elite universities still largely initiate elite students into the corporate ruling class, and themselves embody the competitiveness and preoccupation with status that vex larger society.

This is the bigger societal loss. The money is small compared to what you’ll make in a lifetime. (My debts were only about $15,000 out of college; they seemed much larger than they were.) But we’re letting our most talented students, who could be the next generation of thinkers, be drawn into jobs where they devise new ways to separate workers from their salaries or to help millionaires avoid paying taxes. We’re allowing the big business of college to dominate the real purpose of education, which is to learn to question everything, not make sure you’re on time to your Bain Capital interview.