Writing about fashion, like writing about anything, isn’t easy. It is seriously concerned with the surface of things, which is not to say it is shallow—done well, it is like fly-fishing, a disciplined luxury, its charms elusive to outsiders, its execution deft and sportive. Diana Vreeland’s career began in 1936 with her Harper’s Bazaar column “Why Don’t You?” which ran for a quarter-century. The tone was impish, the taunts self-directed. “Rinse your blond child’s hair in dead champagne to keep it gold, as they do in France,” she wrote—a line of poetry delivered deadpan.

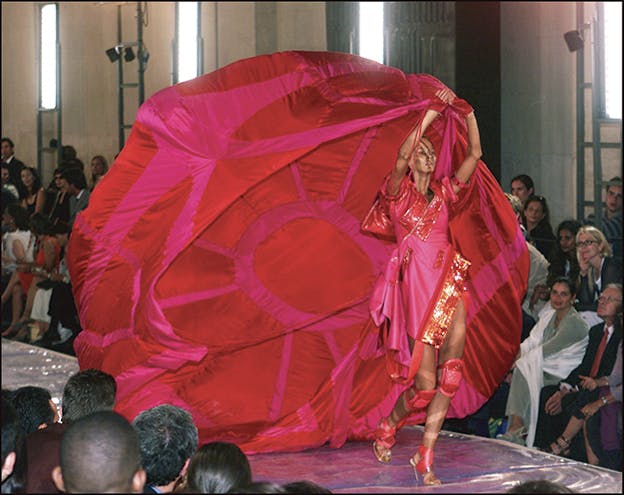

Dana Thomas is a veteran fashion reporter who has covered the industry for decades for The Washington Post and Newsweek, among other publications. She has a comprehensive understanding of how high-end designer-label clothing is made. Her skill is to take a reader through the process, beginning with the snick of inspiration. Next come the hands-on sketches and stitches; access to an atelier and a team of seamstresses; collaborations with milliners and knitters; fittings; castings; and revisions. Finally, it’s showtime, and we get to look over Thomas’s shoulder as editors, buyers, socialites, movie stars, and other iterations of the rich and famous assemble to see and be seen twiddling their thumbs ringside. The music starts, and the models emerge in weird ensembles of wearable art worn just the once. Descendants of the silhouette appear at fundraisers and on the sidewalk, rich ladies in ready-to-wear, teens in copycat cookie-cuts by H&M.

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, Thomas’s newest book, surveys the careers and private lives of two famous English designers. Their trajectories, Thomas argues, are yoked not just by biographical parallels, but by systemic changes within the fashion industry that put global expansion ahead of artistry. She describes the nuts and bolts of distribution and shipping and the profiteers who govern fashion conglomerates, such as LVMH. She explains how couture functions in fashion as a kind of Catherine wheel, the white-hot center throwing off little sparks—logo-ed scents, sunglasses, lipsticks—more affordable to the aspirational upper middle class. Marie Antoinette permitted her peasants to eat cake; LVMH’s CEO Bernard Arnault upsells soccer moms on the sprinkles.

High fashion, it’s scarcely necessary to say, is an extreme, outré slice of the world. The ego and delusion and showing-off that inhabit most, if not all, industries are, to an extent, marketable skills herein. The pace is as breakneck as any field in which there’s real money at stake—Wall Street, the NFL—but the office culture is a species unto itself. A regular job may have you staring at spreadsheets until after 7 p.m., but you compensate with a Sunday picnic, a glass or three of Sancerre sur l’herbe, or a salubrious day hike. If you’ve been logging weeks in the atelier day and night surrounded by bolts of fabric, fragile 15-year-old Estonians draped in unfinished frocks, and ticking clocks whose second hands warp in a different direction depending on whether you’re on speed or Valium, you may not quite know what to do with your downtime.

Galliano and Mcqueen spent a good deal of their downtime in chemically altered states, and their working hours making clothes that are intoxicating. Galliano’s are whimsical, romantic, and nostalgic. They allude to long-gone moments (the Russian Revolution, courtesans in Imperial China) and resemble historical fiction set in motion. He has found inspiration in classic movies and obscure manuscripts—A Streetcar Named Desire, letters exchanged by Freud and Jung about sadomasochism. McQueen, meanwhile, trained as a tailor on Savile Row. He took traditional techniques he’d learned in establishment bastions in rebellious directions. His radical silhouettes included the Bumster-cut pant. McQueen considered the lumbar region, right up to the apex of the ass crack, to be an erogenous zone heretofore neglected by fashion designers, and we can hold him responsible for every glimpse of hip bone above low-rise jeans we’ve witnessed since. He made use of unusual textiles and materials such as Lurex. “He can cut material like God,” said Isabella Blow, the eccentric aristocrat who served as his patroness after she saw his first collection. (She bought just about all of it.) Without McQueen, we might never have beheld Lady Gaga’s apotheosis, and though I’m no Little Monster, I’m a fan of Alexander McQueen. I’m happy he lived long enough to create many collections of insane and amazing clothes. “Savage Beauty,” which was viewed by 650,000 people at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute last year, displayed some of them. The show was one of the most attended exhibitions in the museum’s history, and opened in March at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, McQueen’s hometown.

Both men grew up gay in rough parts of London, attended the Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, made clothes that, from the outset, demonstrated their immense talent, took a turn at directing the famous house of Givenchy while maintaining the lines they had built under their own names, and imploded in spectacular fashion. McQueen hanged himself at 40 in 2010; Galliano blurted racist and anti-Semitic obscenities in a café in 2011 and was promptly sacked by Dior.

Despite this, the parallels Thomas draws between Galliano and McQueen are, for the most part, coincidental. She would like these contours to cohere into a neat parable of comeuppance, but the twin peaks and troughs of their tragic arcs feel manufactured, as predetermined as a Procrustean bed. She mangles the men before tucking them in: Where we anticipate fellow feeling, there’s a void.

Though thick with interesting information, Gods and Kings is baggy and derivative, a thorough clip job larded with quotes from the usual suspects: style writers like Hamish Bowles of Vogue and Suzy Menkes, who has written 1.7 million words for the International Herald Tribune (now the International New York Times), and whom Galliano once called “old pillow head”; fashion world tastemakers such as André Leon Talley; friends and colleagues of both designers; and a smattering of family members. There is a sense that Thomas sought their opinions in lieu of supplying her own. She dutifully attests to McQueen and Galliano’s artistry, but isn’t much interested in the psychology of the artist or the intricacies of addiction or what might contribute to a person’s nervous breakdown or self-inflicted wounds.

So there are no gods or kings in Thomas’s story, just a crew of motley fools and brothers grim—a Leviticus of sin. A failure of empathy gravely taints the narrative, which hinges on two men who, for all their propensity toward publicity, hoopla, and hype, led very private lives. “From afar, the ensemble was chic and sexy,” Thomas writes of one McQueen garment he lined with live invertebrates. “Once you got a closer look, however, and realized what those squiggles were, it made you squirm like the entombed worms.” Squeamishness represents the gist of her feelings toward the dazzling and chaotic pair she has chosen to examine.

McQueen and Galliano are depicted as prodigal sons who, when they aren’t holed up sewing technicolor dreamcoats for the big bad “wolf in cashmere” Arnault, are abusing mutely humiliated slaves. McQueen is said to have had an assistant wash his dildos. Thomas also wishes he hadn’t met quite so many of his boyfriends in bathrooms. “Rather than find another steady beau, he started carrying on with various rough men. ... One reportedly was a porn star named Mr. Stag. Another was an East End gangster.” The Seine, meanwhile, runs with the blood of John Galliano, “badly cut when his glass shower door at home shattered,” forcing him to miss an awards ceremony. There are beggars in rags (“Back at the office, Galliano and [Steven] Robinson researched the subject of homelessness on an aesthetic level”); fairy godmothers (Isabella Blow and Amanda Harlech, Galliano’s respective posh priestesses); and Sodomites licking pillars of salt (no calories). Thomas strikes the pose of an investigative journalist. But the real mysteries, the psyches of her subjects, are scarcely touched. She admires the designers’ handiwork and frowns on their bad manners, abstaining from the delicate, difficult task of considering what might have motivated them. Instead they are cast as ticking time bombs—props—in a morality play populated by caricatures whose machinations remain abstract.

Thomas’s 2007 book Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster was gutsy, taking high-priced leather goods mass-produced by Prada and Gucci and turning them inside out to reveal their shoddy seams. Those were things; Galliano and McQueen are people. Indignant finger-pointing works better on the former than the latter. It may be that the author is out of her depth. Fashion writing’s first principle is that beauty makes us happy, as it should. Negativity is rare, and indirectly conveyed. A raised eyebrow, an invitation that never materializes, these are the industry’s accepted cruelties, more elision than hostility. Venturing into darker territory, Thomas seems perennially scandalized, a stance that gets in the way of her asking—let alone answering—thorny questions that deserve attention. Questions like, at what price genius? Does male homosexuality mean something different when it’s channeled into designs for women? When is fashion an authentic expression of change, and when is it the emperor’s new clothes?

In the end, there is no one to root for: not the avaricious corporates; not the appreciators, oh-darling types or “pierced, pot-smoking punks”; certainly not the overgrown man-children playing dress-up when they aren’t tossing their toys out of the crib. McQueen, according to one fashion writer Thomas waggishly quotes, is “tongue-tied and chubby, with an open, childlike face that should have been advertising baby food.” “When Anna Wintour took him to lunch at Forty Four ... he ordered lobster and chowed down on the pricey crustacean with his mouth open, slobbering melted butter down his chin as he told her his ambitions. Wintour was said to be appalled.” Galliano, a “wild and debauched deviant,” fares no better. After his obscene outburst, has he seen the error of his ways? In 2013, he davened his contrition on “Charlie Rose,” but Thomas seems to bear a grudge, stating that Galliano “put forth the overworked-self-medicated argument in what felt like a very rehearsed script.” Yet the fashion establishment has forgiven him—in October, he became creative director of Martin Margiela (“remake-and-mend,” “Belgian, serious, the antithesis of extravagance and showing off,” per Suzy Menkes).

“I wasn’t born to be loved,” Galliano told Thomas. “I’m not interested in being liked,” said McQueen. Those we anoint genii often pay a high price for their gifts. This we know from other pursuits: Virginia Woolf, Jimi Hendrix, Charlie Parker, Vincent van Gogh. Their talent is never fully under control; it’s a fetus with a strong kick.