Seven years ago, Richard Alley, a prominent climate scientist who studies melting glaciers, briefed ten U.S. senators on a congressional trip to Greenland, on which they took helicopter and boat rides to visit icebergs the size of coliseums. For the senators, the trip amounted to a crash course in climate science.

Alley, a Penn State professor, was there as an educator. He explained that if Greenland ice melted entirely, it alone would be enough to raise sea level 23 feet. He assured the lawmakers that the science on the subject was solid, and that climate models are accurate. He didn’t advocate for policy solutions, but he left optimistic that the facts and the experience of viewing the shrinking ice would inform the lawmakers going forward.

A Republican senator on that trip recalled it differently. In a March speech on the Senate floor, Georgia’s Johnny Isakson invoked Alley’s name while disputing the causes of climate change. “Seven years ago I went with Senator [Barbara] Boxer from California to Disko Bay in Greenland with Dr. Alley,” Isakson said. “And there are mixed reviews on that, and there’s mixed scientific evidence on that.” Based on lawmakers’ questions during the trip—“the kind of questions a reporter may ask,” Alley said—nothing indicated to the professor that at least one of them missed the basics so badly.

On climate matters, the GOP in recent years has become a caricature: a Flat Earth Society, as President Barack Obama says. Only five Republican senators agreed on a January amendment that said climate change is caused by humans; 49 voted against it. The most outspoken climate-change deniers, such as Oklahoma’s James Inhofe, who now chairs the Senate environment committee, have risen to leadership positions. Republicans are usually content to attack the evidence that tells us the climate is changing, but in the 2014 midterm election, they evolved a smidge, and took to brushing aside climate questions by downplaying their credentials: “I’m not a scientist,” they’d say, as a sort of verbal shrug.

Yet many Republicans, including those who reject the science, have met with scientists who have made the facts clear. This is the side of the climate discussion the public rarely hears about. A number of Republicans are meeting with experts, nearly always off the record, sometimes extemporaneously, and often in some strange settings.

Scientists say that Republican policymakers are generally more receptive to the inescapable facts about climate change than their party’s public stances would suggest. The GOP’s problem isn’t ignorance; scientists and the media are making the mechanisms and the stakes of climate change obvious. Rather, the politics are too strong. Feigning ignorance gives Republicans cover from their insistently climate-oblivious base.

David Titley, a former Navy officer and founder of the Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk, once met six Republicans and Democrats near—of all places—Buckingham Palace in London. They were part of a congressional delegation, and the politicians (three of whom are still in office) had an informal conversation with Titley, walking across a big field after a day of meetings. Titley said his takeaway from this stroll was that not all Republicans were in “Senator Inhofe’s camp,” and that there was a reasonable middle searching for a way to acknowledge the changing climate without jeopardizing their jobs. “They certainly understand where the politics are,” Titley said. “But they’re not denying the science. They say of all the issues, this is not high in the constituency’s mind, and what’s the upside?”

He added: “No one wants to be the next Bob Inglis.”

Inglis’s name has become cautionary shorthand among conservatives. The six-term South Carolina congressman lost his seat in the 2010 primaries to a Tea Party challenger. Though attacked for a number of his more moderate votes, he’s mostly remembered for speaking out on the reality of climate change. And that’s what political observers say sunk him.

Inglis hovers unacknowledged when politicians offer excuses to experts for continuing to ignore the climate. “I’ve had staff tell me that directly, that they’re scared of the political impact “of getting too far out on the issue,” Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists said. Andrew Moylan, of R Street, a libertarian think tank that argues for a revenue-neutral carbon tax to address climate change, echoed that analysis. “Certainly that’s implicit in the political assessment of some folks who say ‘We’re with you,’” he said. “The implicit assumption is they don’t want to suffer the political consequences on a tough issue.”

Inglis himself concedes their point. “Am I the worst commercial for it, in other words?” he said in a phone interview. “Well, yes,” he added, then laughed.

His experience in Congress proved that curiosity can inform political conviction. Inglis met with scientists, too. On trips to the Great Barrier Reef and to Antarctica, he met with scientists Scott Heron and Donal Manahan—both of whom Inglis credits, along with his son, for changing his opinion of the science. One conversation he had with Manahan, in which they discussed the effects of an acidic ocean on coral, ran past its allotted 20 minutes to nearly an hour.

Inglis, alas, is an exception.

University of Miami climate modeler Ben Kirtman was one of two scientists in 2012 who met with a 2016 GOP contender he declined to name, citing their agreement to stay off the record. “At first it was an opportunity,” Kirtman said. “The subject was really combative, and he was really skeptical when you gave him the pile of evidence.” But over two hours with the candidate, the scientist thought he made some progress. “When I sit down and brief the most skeptical of skeptics, they start to crack. They start to say, ‘Oh I’ll give you that.’” Where did Kirtman see cracks? The candidate seemed to accept that the climate has warmed since the 1950s, driven primarily by human activities. He even seemed willing to accept that we need to reduce pollution to mitigate climate change. Where he remained unconvinced was on the projections out to 2100, which depend largely on what we do now to cut pollution. “It was really hard for him to bite off the doom-and-gloom scenario,” Kirtman said.

When reporters are in the room to witness these exchanges, we find out what was said—which isn’t much. Florida Governor Rick Scott granted scientists a highly publicized, 30-minute meeting last summer, after saying during his reelection campaign that he can’t comment on climate change because he’s, yes, “not a scientist.” He filled half the time with small talk, allotting the five Florida experts three minutes apiece to give presentations. When the time was up, he left immediately. Eckerd College’s David Hastings described the governor’s face as showing “no expression of his interest or concern,” giving the session the air of a chore. Hastings felt like he played into Scott’s political strategy. But maybe, he hoped, explaining the historic ice core data and projections for sea level rise helped a little.

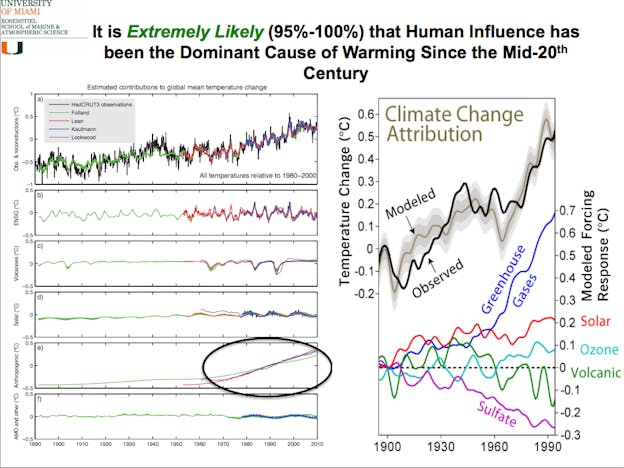

The experts’ presentation was packed with graphs showing centuries and millennia of data, and left little room for doubt that Florida was in peril: Seas two feet higher by midcentury would cover more than a quarter of the state’s southern counties. One slide addressed the myth that temperatures stopped rising during the past decade. “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal (100 percent),” it said, and ended by noting that it is “extremely likely (95 percent-100 percent) that human influence has been the dominant cause of warming.”

Republicans who duck climate questions by insisting they aren’t scientists should listen to such expert analysis. But Republicans are just as adept at dodging climate tutorials.

Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado made a series of uninformed statements about the study of climate change last fall, when he wavered between acceptance and denial. Later, Gardner backed his colleague Ted Cruz’s assertion that NASA should abandon Earth sciences. “Are we focusing on the heavens in NASA?” Gardner asked at a hearing. “Or are we focusing on dirt in Texas?” As part of a small group of scientists coordinated by the Union of Concerned Scientists, Kevin Trenberth, a scientist who operates out of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, reached out to advise his senator on climate issues.

He’ll only get that meeting if Gardner agrees to be in the same room. “It’s much easier if people want to know and are keen to know the information,” said Trenberth, who in past years has met with Democratic politicians, including Al Gore and ex-Colorado Senator Mark Udall.

Since Trenberth’s request, which included emails and a formal letter in February, Gardner has taken at least two trips for congressional recess back to Colorado. So far, every date Trenberth has suggested turns out to be a time when Gardner is busy.

While Trenberth gets the runaround, Inglis is heartened by the movement he sees on the right. Republicans largely shifted from outright denial during the recession to the merely agnostic crouch of not being scientists. “Sure, it’s scary to politicians, watching another politician go down to the beat,” Inglis said. “But those were different times.”

Politicians’ ignorance isn’t what is holding the GOP back, Inglis said. Inaction is the bigger culprit. The party must mobilize its constituency and prod them to adapt, he said: “Politicians will lead the parade wherever it’s going.”

This story was updated to reflect the version that appeared in the May 2015 issue of our magazine.