Most Americans hate today. After all, it’s Tax Day—and no one likes seeing the federal government take a large chunk of their income. (Well almost no one.)

As the 2016 campaign gets underway, candidates, especially those on the right, will compete to see who can propose the largest tax cut. Senator Marco Rubio currently is in the lead with his recently released tax plan that would reduce government revenues by $4 trillion over the next decade. Senator Rand Paul has promised "the largest tax cut in American history." Senator Ted Cruz will surely try to top them both. On the left, Hillary Clinton will almost surely never endorse a tax hike. She may even follow in President Barack Obama’s footsteps and promise never to raise taxes on the middle class.

Don’t believe any of them. In the coming years, the federal government is going to need more revenue. Nothing any politician says can refute the basic math that Americans are growing older and that’s going to cost a lot more money. But that doesn't mean tax rates have to rise. In fact, Congress could increase the federal government's revenue by hundreds of billions of dollars a year, while making the tax code more progressive—without raising current tax rates.

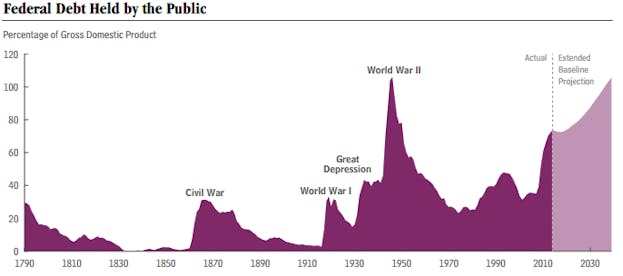

While the near-term deficit is no longer a problem, spending is still projected to rise considerably over the next few decades. The Congressional Budget Office’s most recent long-term budget outlook, released last July, forecasts debt rising from 74 percent of GDP in 2014 to 106 percent of GDP by 2039.

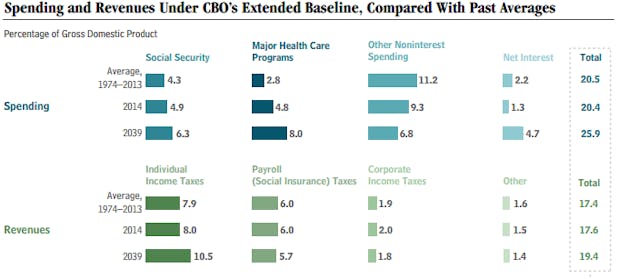

CBO attributes rising debt to three causes: the Medicaid expansion and health care subsidies in Obamacare; excess health care cost growth; and, most importantly, all of this aging.1 By 2039, the proportion of the U.S. population over age 65 is projected to rise by half, from 14 percent to 21 percent. All those retiring baby boomers will need health care and will expect to receive Social Security benefits. That shows up in CBO’s projections: Social Security spending is projected to rise from 4.9 percent of GDP last year to 6.3 percent in 2039, while Medicare spending is projected to rise from 3 percent of GDP to 4.6 percent of GDP in the same span.

CBO also offers specific estimates for why Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security are getting so expensive: 55 percent of it owes to people aging, 24 percent is because of excess health care cost growth, and 21 percent is because of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion and exchange subsidies. The majority of increased spending, then, is the result of demographics, not waste or excessive health care spending.

At the same time, excess cost growth is becoming less and less of a problem. While the causes aren’t entirely clear, health care cost growth has slowed considerably during the past few years. In health care language, we have bent the cost curve. This is already paying dividends. In 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projected that health care spending from 2014 to 2019 would cost Americans $23.6 trillion. But new research from the Urban Institute reduced that estimate to $21 trillion—a 10 percent drop in just a few years.

It’s not clear how much of this bend owes to the slow recovery, increased cost-sharing via higher deductibles and co-payments that encourage consumers to limit their use of health care services, and Obamacare. If the weak economy turns out to be responsible for costs slowing, then costs will likely grow faster in the coming years. But health care cost growth remains low by historical standards, even as the recovery strengthens. More than a temporary change, this shift points to lower health care costs for decades to come. Yet debt will continue to escalate. The big culprit, then, is aging—something largely outside of government control.

Given all of that, how should we address our long-term debt?2 For one, we should continue trying to bend the health care cost curve. Democrats and Republicans have very different ideas about how to do that. But even if we eliminated excess cost growth, the debt will still rise significantly.

We face the choice to do nothing, cut spending, or raise revenues. Republicans like to describe the government as a bloated, bureaucratic nightmare. But that's not really the case. For instance, former Senator Tom Coburn, who retired at the end of the 113th Congress, used to release an annual "Wastebook" that described egregious examples of government waste. The 2014 version named 100 federal projects that cost the taxpayer $25 billion. That sounds like a lot. But many of those have legitimate purposes. More importantly, $25 billion is a mere sliver of the $3.5 trillion the government spends annually. At 0.7 percent, it's close to a rounding error.

Presumably, if the government wasted far more money, Coburn would have found it. His "Wastebook" actually demonstrates that the federal government is relatively efficient. GOP plans for cutting spending cannot achieve their ends solely by eliminating waste. Instead, politicians are left to shred programs Americans really like: medicine for the poor, food for hungry children, national parks, grants for college students.

During the past 40 years, the federal government has spent an average of 20.5 percent of GDP while collecting revenues equal to 17.4 percent GDP. In 2039, CBO projects spending will rise to 25.9 percent of GDP while the government collects just 19.4 percent of GDP in revenue. But as noted above, that increase in spending largely results from Americans' aging. Thus, if conservatives seek to address the long-term debt through spending cuts, either the federal government must become much, much more efficient, so that it delivers the same level of services to Americans for less money. Or it will deliver fewer services altogether. That’s the unavoidable result of so many of us growing older and thus becoming less productive and more reliant on the government.

Even more, while spending on entitlement programs is projected to rise considerably, spending on the rest of the federal government, including food inspectors and the IRS and the military, is projected to decline. These areas are already projected to shrink. Funding on everything other than Social Security and the major health programs is projected to fall from 9.3 percent of GDP last year to 6.9 percent of GDP in 2039. It's hard to imagine future Congresses allowing that to happen. Already, federal agencies are strained because of a lack of funding. Budget cuts at the IRS, for instance, have crippled morale and forced the agency to cut back on much-needed services for taxpayers. Further spending cuts would damage agencies across government, decreasing the number of food inspections, increasing wait times for regulatory permits, and harming a vast number of other government functions. If I'm right and future Congresses don't allow spending to drop much further, then CBO is actually underestimating the rise in long-term debt.

What about doing nothing? While conservatives still deem our long-term debt an imminent problem, that’s not really the case. Deficits are declining and the debt is barely projected to rise over the next ten years. Liberals are right to argue that we have some time to figure this out. Other problems, like global warming, deserve higher prioritization. But they shouldn't ignore the long-term debt altogether. While economists no longer believe that a debt-to-GDP ratio above 90 percent is necessarily more risky, they also don't know when investors might demand higher interest rates on U.S. debt, raising interest payments and crowding out other spending.

Chances are we're not close to that point now. Interest rates are near historic lows and the dollar remains the world's reserve currency. But it's still a risk. Furthermore, if another economic crisis hits, Congress needs the political space to pass another stimulus. Right now, that space does not exist; Congress would never assent to another major round of fiscal stimulus. But if policymakers reduce our long-term debt, that space may open up—and could have major benefits during the next recession.

All of this leads to one conclusion: The federal government needs more revenue. Liberals should (and do) support this most of all, since it will cost money to fund an expansion of Social Security, for instance, or to pass universal pre-kindergarten. But conservatives should support this as well, particularly if they are concerned about the long-term debt.

There are two main ways to generate that revenue. First, we could raise marginal tax rates. Those tax increases would focus on the rich, making the tax code more progressive. But the middle class would also see their taxes rise, too. We can soak the rich only so much.

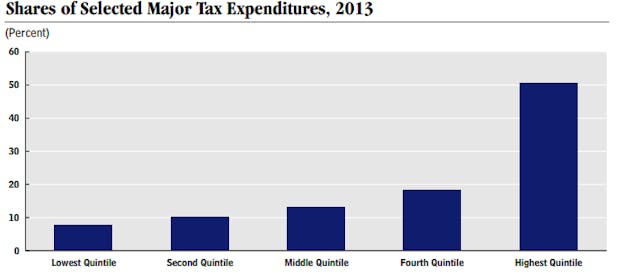

Second, we could curtail tax expenditures—the different tax credits, deductions, and exemptions that lower tax liability for millions of Americans. In 2013, tax expenditures cost the federal government nearly $1 trillion, or nearly 6 percent of GDP. That’s more than we spent in total on Medicare and is nearly as much revenue as the federal government took in through individual tax returns. Worse than the lost revenue, tax expenditures benefit mostly the rich. The top 20 percent of earners get about half of that money. Less than 10 percent goes to the bottom quintile.

Cutting the home mortgage interest deduction, exclusions for pensions contributions, and ending the “stepped-up” loophole that allows rich heirs to avoid the estate tax would rake in billions and make the tax code more fair. This strategy could even appeal to conservatives, as it wouldn’t require marginal tax rates to rise. Economists consider tax expenditures as spending, in fact. Conservatives who want to cut spending should start by curtailing tax expenditures.

There's one other way to reduce the long-term debt without cutting spending or reducing revenue: increase economic growth. When analysts look at long-term debt, they measure it in terms of GDP, as I have done throughout this article, because GDP represents the U.S. revenue base. Growth reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio and makes long-term debt smaller in comparison to the economy at large.

In that sense, policies that promote growth may be the best solution to our debt problems. Yet we shouldn't rely on them alone. It's difficult to design policies that drive growth. The economy is massive, and the federal government has limited ability to steer it. Policymakers should aim to promote growth while also improving the lives of Americans and solving our long-term debt problems.

I don’t expect Hillary Clinton, much less a Republican candidate, to produce a platform that accomplishes all of those goals. A tax plan that increases revenue by closing tax breaks is not a political winner, so long as the economy is in recovery and wage growth remains weak. But at some point, we're going to need to raise more revenue. The longer politicians pretend that that isn’t the case, the harder it will be to accomplish.

CBO defines excess health care cost growth as “the extent to which health care costs per beneficiary, adjusted for demographic changes, grow faster than potential GDP per capita.”

By "address," I mean putting debt on a downward path. Economists generally agree that the deficit should equal 3 percent of GDP. I'm not suggesting we should try to balance the budget or reduce debt to zero.