Comedy used to elicit laughter, but now more commonly produces earnest debates. We live in a time when the borderlands of mirth are closely guarded, leading to skirmishes about the permissible limits of humor. Were the Charlie Hebdo cartoons fair satires of religion or racist attacks on a besieged minority group? Should Trevor Noah’s tweets disqualify him from hosting The Daily Show? Is Lena Dunham better or worse than Hitler?

One way to resolve these questions is to look at an extreme test case. Richard Pryor was one of the greatest, most influential comedians of the past century, but also a man who took comedic offense about as far as it could go. Few, if any, comedians have been as remorseless as Pryor in aggressively poking touchy subjects such as race and gender. His stand-up routine, especially in his peak decade of the 1970s, was a baffling mixture of hilarity and pain. Fellow comedians such as Whoopi Goldberg and Robin Williams revered Pryor as a pathfinder and genius, but his comedy also provoked criticism for allegedly promoting racism (Pryor was free and frequent with his use of the n-word) and sexism (the word “bitch” sprang easily off his tongue).

In his 1971 album Craps, Pryor drew on his many run-ins with the police to talk about the indignity of strip searches. “You talk about degrade a nigger,” he quipped. “They degrade you immediately. I don’t know what they be looking for. ‘What you be looking for in my ass? Ain’t nothing in my ass. If I had a pussy, I might dig it, because you can hide something in your pussy. But in your ass—what am I going to hide in my ass? A pistol? Come out with a .45?’ ‘Up against the wall, motherfucker’!”

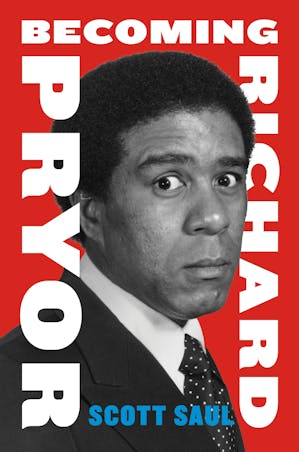

It’s not so much that Pryor was a genius who happened to give offense; rather, offense-giving was the core of his genius. Although his comedy was enlivened by his supreme gifts for mimicry, pratfalls, and pacing, the real essence of his talent was his ability to make his audience uncomfortable. Other offensive comedians can be dismissed as lacking in skill—a common response to the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, Trevor Noah’s tweets, and Dunham’s New Yorker piece comparing Jewish boyfriends with dogs. This escape hatch doesn’t open in Pryor’s case, since only the terminally humorless can resist his talent. How do we reconcile Pryor’s undeniable offensiveness with his uncontestable brilliance? Scott Saul’s revelatory biography, Becoming Richad Pryor, helps answer this question.

Richard Pryor was born in Peoria, Illinois in 1940 to a family of criminals, and grew up in a brothel. The matriarch was Pryor’s formidable grandmother Marie, a madam who looked after a bevy of sex workers with a sometimes violent hand, tempered with outward displays of maternal affection. Pryor’s father was a pimp; both his biological mother and stepmother were prostitutes; and one of his uncles was a drug runner and counterfeiter. The house of ill repute was also a house of pain, with the young Pryor living in terror of his violent father. Pryor was also sexually abused by a neighbor.

Comedy was a release from this dire childhood. Although the racist school system of the time offered little encouragement, Pryor did manage to carve out a social role as a class clown. He couldn’t talk to his friends and classmates about his bizarre and sometimes dangerous home life, but joking offered another way to connect. As a ninth grade drop out, Pryor had few prospects—he worked variously as a shoeshine boy, janitor and bartender. Stand-up comedy offered a way out of this dead end, even at the low pay he initially earned since he was relegated to the “chitlin' circuit” reserved for black comedians.

Pryor’s early success as a comedian came from wearing a mask, a borrowed one. He carefully modeled his persona in imitation of Bill Cosby, already in the early 1960s a crossover star whose folksy, clean, and nostalgic stories appealed to a large white audience. Variety described Pryor as belonging to the “Cosby school of reminiscing and identifiable storytelling.” As Pryor himself sheepishly confessed, “for about a year I was Bill Cosby.”

In the late 1960s, radicalized by the rise of the Black Power movement and personally dissatisfied by the inauthentic identity he had crafted to appeal to a white audience, Pryor started to do bolder comedy that dealt more frankly with his plebeian background. His turn to obscenity was motivated by a desire to speak openly about the disreputable milieu that created him, which he called “the backside of life.” As Saul shrewdly notes, for Pryor, “life itself was unclean, profane. He couldn’t be clean and be true to the characters he wished to portray.”

Pryor’s best work was a great eruption in American culture, making audible voices never heard before by a mass audience. As Saul writes, Pryor gave “an unvarnished portrait of the black community’s chippies, hustlers, jackleg preachers, and winos. He took his audience to the inner sanctums of the black experience—the ‘members only’ all night clubs, storefront churches, barbershops—and captured the human variety he found there, channelling voice after voice with an ease that suggested there was no limit to their number.” Pryor became the anti-Cosby.

Pryor was bold in his words but not in his demeanor. He wore a defeated expression, his suspicious side-eyes measuring the audience to see if they could handle the truth. Cosby practiced the comedy of complicity, inviting us to chuckle along with him in shared amusement at some foible. Pryor engaged in something much more difficult: the comedy of vulnerability, daring us to find affinity with experiences far outside our comfort zone. Cultural fault lines can still be gauged by the nervousness of the laughter he provoked: in the early 1970s audiences didn’t know what to make of the fact that Pryor, ostensibly heterosexual, occasionally alluded to having sex with men on the down low. Such revelations would still make many uneasy in 2015.

Pryor practiced the comedy of liberation: he shocked because he spoke of all the things that traditionally went unsaid. His salty language was part of that liberation. The novelist Ishmael Reed, who befriended Pryor in the early 1970s, once argued that the “great restive underground language rising from the American slums and fringe communities is the real American poetry and prose.” Like Reed’s novels, Pryor’s stand-up was an attempt to make art from that “great restive underground language.”

The liberation offered by comedy can only take you so far. You can’t have the sort of childhood that Pryor had and be unscathed, even if you learn to joke about it. Pryor’s personal life remained a mess, with both his drug abuse and occasional outbursts of violence traceable to a blighted youth.

Like Dave Chappelle after him, Pryor was also alive to the ambiguity of creating comedy about the black experience, especially when consumed by a largely white audience. Pryor’s abrasive persona ran the risk of conforming to stereotypes about the crazed and dangerous black man.

A similar ambiguity attended Pryor’s use of the n-word, which he was conflicted about. In his autobiography Pryor Convictions (1995), the comedian describes taking up the word in the 1970s in an active effort of cultural detoxification: "Nigger. And so this one night I decided to make it my own. Nigger. I decided to take the sting out of it. Nigger. As if saying it over and over again would numb me and everybody else to its wretchedness. Nigger. Said it over and over like a preacher singing hallelujah." But after a 1979 trip to Kenya, where he was impressed by the unself-conscious pride of the people, Pryor said he came to regret “ever having uttered the word 'nigger' on a stage or off it. It was a wretched word. Its connotations weren't funny, even when people laughed.”

Despite this disavowal from the comedian himself, Pryor’s legacy argues for a more complicated judgment. The abrasiveness and ugliness of some of Pryor’s work was inextricably part of the liberation they contained. If Pryor hadn’t risked saying awful things, he wouldn’t have also said true and necessary things. Pryor’s comedy opened up a world that needed to be made visible. The problem with recent attempts to police the borders of comedy is that they risk foreclosing the possibility of comedic liberation.