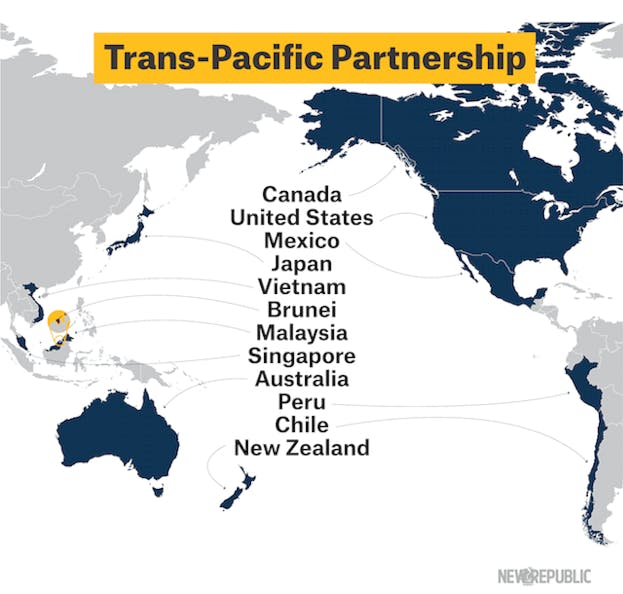

Last month, at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C., AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka gave a 29-minute speech in opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a massive 12-country trade agreement that the Obama Administration hopes to complete this year. “At the end of the day, the partisan battles are really just so much noise,” he said. “For me, it’s all got to come back to one simple question: Is our trade policy working for America’s workers and for our nation as a whole? And the simple answer to that question is it isn’t.”

In their debate afterward, Trumka and Adam Posen, the president of the host institute and a supporter of the TPP, sometimes couldn't even agree on basic facts, like how many manufacturing jobs Germany has lost in the past 20 years. Often they resorted to generalizations instead: At one point in the largely cordial conversation, Trumka said to Posen, “I know you are a dyed-in-the-wool free trader. If I cut you open, little NAFTA balls would fall out of you.”

The crowd laughed, but the remark represents what makes trade agreements so impossible for policy journalists to understand. Opponents of the TPP like Trumka insist that its supporters think just about any free trade agreement will be good for the United States, regardless of its details. On the other side, supporters of the TPP insist they’ve learned from the failures of NAFTA; this time, they say, the trade agreements will benefit American workers.

Who is right? I don't know—and I’m not the only one. Writing at Vox, Ezra Klein said he was in the “undecided camp,” while Matt Yglesias called the TPP “one of the most frustrating things to cover in my career.” New York Times columnist Paul Krugman came out against the deal, while wondering why the president is spending so much political capital trying to pass it; David Wessel, writing for the Wall Street Journal, recently wondered why labor unions are working so hard to block it. If anything is clear about the TPP, it’s that no one knows exactly why everyone cares so much.

But talk to the key players in the debate, and it becomes clear that the TPP is the most important economic fight happening in Congress this year and one of the most important of Obama’s presidency. For once, it's not a partisan debate. Many on the right, including Representative Paul Ryan, support the deal, while the White House has faced the most intense criticism from members in its own party. The intraparty party fight often resembles the Trumka-Posen debate: high on rhetoric, short on substance. But it's possible to cut through the noise and discover the real issues at play. Here are the four most contentious parts of the trade pact:

This Is Not About U.S. Jobs

It's been more than two decades since President Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the left still disagrees significantly on how NAFTA affected U.S. workers. Many liberals, for instance, blame NAFTA for the 29 percent decline in manufacturing jobs since 1994, while acknowledging that other factors, like globalization and technological change, have contributed to job losses and wage stagnation, too.

That complaint about NAFTA, whatever its merits, is informing much of the liberal opposition to the TPP. It shouldn't: Supporters and opponents of the TPP largely agree that its direct effect on the U.S. economy will be minor.

“There are going to be very few jobs that will be affected,” said Robert Scott, the director of trade and manufacturing research at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, who opposes the deal.

Jared Bernstein, formerly the top economist for Vice President Joe Biden, who hasn’t formulated a final position on the TPP, agreed. "I think most economists who understand these dynamics and even have modeled them will argue that there’s not much of a jobs impact from these kinds of deals,” he said. "I would largely discount the large job loss estimates as well as the large job gain estimates."

“I don't think we're talking about an enormous impact on the U.S. economy,” said Gordon Hanson, an economist at the University of California, San Diego, who focuses on international economics and supports the TPP.

Of course, there has to be some impact. The trade deal will directly affect American workers in two ways. First, it will reduce tariffs in the Pacific region, particularly in the services industry where the U.S. has a competitive advantage. (While some services, like a plumber or a barista, obviously cannot be traded between countries, others are increasingly tradable in our globalized economy—financial analysts, lawyers, and consultants, to name a new.)

“Existing trade agreements don't deal very well with services,” said Hanson. “This trade agreement gives an opportunity to put the major sectors of the economy on equal footing.”

Since the U.S. is a very open economy, its tariffs are currently lower than those in the TPP countries. In other words, U.S. exporters face higher barriers to trade than TPP exporters face to trade with the United States. Reducing those barriers benefits U.S. workers.

Second, the TPP also includes enforceable labor standards. These rules will require foreign countries to strengthen their laws including implementing a minimum wage, setting maximum work place hours and granting workers the right to collectively bargain. All of these things will raise the cost of foreign labor, giving U.S. companies fewer economic incentives to ship jobs overseas. “We have learned from one generation of agreements to the next how best to shape globalization,” Froman said.

Labor groups and progressive economists are not convinced that these standards will actually do much to help U.S. workers. The agreement may have a formal mechanism for enforcement, they say, but it doesn’t mean the U.S. will actually use it.

The left also rejects the Obama administration's argument that without the TPP, China will set the labor standards in the region through a trade agreement it is currently negotiating. "I don't think China setting the rules with these other countries is going to have such a big impact on the United States as some would suggest," Scott said. Still, it's hard to imagine any way that the TPP's labor standards would actually make U.S. workers worse off.

“I ask people, 'Why would you block us from raising workers' standards in Vietnam?’” Froman said. “Through TPP we’re on the verge of historic labor progress, and that will bring a better life to people in other countries and a more level playing field for our workers.”

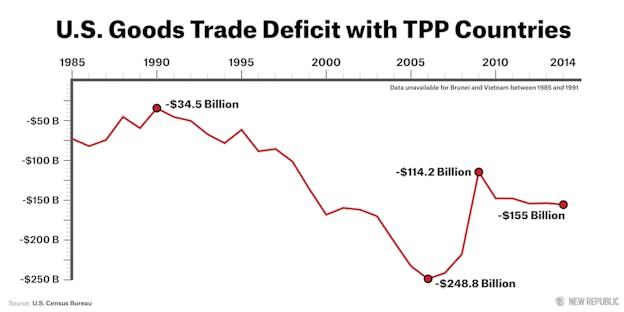

Why Won't the U.S. Address the Trade Deficit?

Economists across the political spectrum believe that the U.S.’s large trade deficit—the difference between its imports and exports, which was $505 billion last year—causes significant damage to the economy. Think about it this way: When Americans buy foreign goods and services, they are supporting jobs in foreign countries. The more that imports exceed exports, the more U.S. trade is helping to support foreign jobs.1

But reducing the trade deficit is easier said than done. Ideally, the TPP would restrict countries from artificially lowering the value of their currency to boost their own exports and hurt U.S. exports, but there's no chance of such a provision in the TPP. Much of the world thinks that the Federal Reserve manipulated the dollar through its quantitative easing programs, so any chapter on currency manipulation that could possibly receive approval from the 11 other TPP countries would have to put restrictions on the Fed—something the Obama administration would never agree to, rightfully.

Liberal economists understand these dynamics, but many are sick of the Obama administration—and prior administrations—refusing to address the trade deficit. In December, Bernstein authored a blog post titled, “Without a currency chapter, the TPP should not be ratified.” When I asked him about it, he said, “My position has softened since then. I think I’ve been moved by administration arguments that a currency chapter would queer the deal and I think that’s a pretty strong argument.”

But he still had a major problem with the White House's stance.

“What I view as unacceptable,” he said, “is the position that we can’t do anything in the TPP and we can’t do anything out of the TPP and therefore we just have to live with the status quo.”

What Elizabeth Warren Hates About the TPP

No part of the TPP has invoked such over-the-top rhetoric than the section on Investor State Dispute Settlements (ISDS). “Agreeing to ISDS in this enormous new treaty would tilt the playing field in the United States further in favor of big multilateral corporations,” Senator Elizabeth Warren wrote in a Washington Post op-ed. “Worse, it would undermine U.S. sovereignty.”

Warren overstates the risk. ISDS is a mechanism for multinational corporations to seek redress from an international tribunal if they believe a country has unjustly expropriated their investments. In other words, if Malaysia unfairly seizes a U.S. company’s factory, the company can challenge Malaysia through an international tribunal and receive compensation. But the opposite is true too: Foreign companies can challenge the U.S. through these tribunals if they believe the U.S. has expropriated their investment.

Liberals have a number of problems with ISDS.

“We consider it inappropriate to elevate an individual investor or company to equal status with a nation state to privately enforce a public treaty between two sovereign countries,” Lori Wallach, the director of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, said, adding, “[ISDS] gives extraordinary new privileges and powers and rights to just one interest. Foreign investors are privileged vis-a-vis domestic companies, vis-a-vis the government of a country, [and] vis-a-vis other private sector interests.”

Wallach is right that foreign investors will have an avenue separate from domestic companies to seek redress from expropriation. But ISDS supporters see that as a good thing, for two reasons: it reduces the risk foreign companies face in investing in certain countries with weak judicial systems; and second, it prevents commercial disputes between a country and a company from becoming international political disputes between two countries.

The U.S. has won all 13 cases that have reached completion before an ISDS tribunal. During the same period, foreign companies brought hundreds of thousands of cases against the U.S. in domestic courts. “It's not that people don't sue us on these claims,” Froman said. “It's that they use the courts, because through the courts in the U.S., you can get a rule overturned, you can get a law overturned. You can't do that through ISDS.”

But other developed nations have not been as successful as the U.S. has. Australia, for instance, has been sued by American tobacco companies over regulations on cigarette packages. Not coincidentally, Australia is balking at the inclusion of the ISDS in the TPP.

“As far as U.S. courts—yes, they have a robust caseload,” Wallach wrote in an email. “But this does not negate the basic reality of ISDS: it provides foreign investors alone access to non-U.S. courts to pursue claims against the U.S. government on the basis of broader substantive rights than U.S. firms are afforded under U.S. law.”

When Should Copyrights and Patents Expire?

To promote the arts and sciences, the federal government grants artists and inventors a temporary monopoly over their work in the form of copyrights and patents, respectively. Without intellectual property law, artists would have little ability to profit from their creative output and pharmaceutical companies would have little incentive to invest in new drugs. The limited monopoly creates that incentive—but one that the state must balance with the interests of society.

Right now, many believe that the balance has swung too far in the direction of artists and inventors. Currently, copyrights don’t expire until 70 years after the death of the author. While liberals are looking to roll back these laws, the Obama Administration is exporting them to other countries through the TPP, making even supporters of the deal uneasy.

“I think this is a legitimate concern,” said Gordon Hanson, the UCSD economist who supports TPP.

“You might try to argue that there is a US interest in enhancing IP protection even if it’s not good for the world, because in many cases it’s US corporations with the property rights,” New York Times columnist and economist Paul Krugman, who opposes the deal almost entirely due to the IP provisions, wrote. “But are they really US firms in any meaningful sense? If pharma gets to charge more for drugs in developing countries, do the benefits flow back to US workers? Probably not so much.”

A theme runs through these four disagreements: They're overrated. The actual effects of the TPP are exaggerated. Labor unions warn about mass job losses and the Obama Administration touts the significant labor provisions in the law, but the academic evidence largely points to small job losses or gains. The left demands a chapter on currency manipulation while knowing that the 11 other TPP countries will never accept one without significant restrictions on the Federal Reserve. Even for Washington, a town where every policy decisions becomes a massive lobbying free-for-all, the TPP seems overblown.

Until, that is, you consider what’s really at stake with the TPP.

"I think its larger importance is trying to establish a new framework under which global trade deals will be done,” said Hanson. “Now that the [World Trade Organization] seems to be pretty much ineffective as a form for negotiating new trade deals, we need a new rubric."

Looked at through that lens, it makes sense why both the unions and the Obama administration have spent so much political capital on the TPP. If the TPP sets the framework for future trade deals, it could be a long time before unions have the leverage again to push for a crackdown on currency manipulation. They understand, as the Obama Administration and many interest groups do, what much of the media doesn't: The TPP isn't just a 12-country trade deal. It's much bigger than that.

When I shared this theory with Jared Bernstein, he began to rethink his position. “When you put it that way, I kind of feel myself being pulled back into the initial title of my post,” he said. “In other words, if this is the last big trade deal, then perhaps the absence of a currency chapter is a bigger deal than I thought.”

If the TPP could determine the course of global trade for decades to come, then each interest group has a huge incentive to fight for every last policy concession. It explains why labor and business groups are putting huge amounts of money into this fight. That money and the accompanying rhetoric has only made it harder for policy journalists to cut through these complex debates. It may take decades before we really understand the stakes of the TPP.

This isn’t a perfect analogy. Some imports in the U.S. are used as intermediate goods and some imported goods do not compete with U.S. goods and thus don’t displace U.S. production. But overall, a larger trade deficit means more American demand is promoting foreign jobs.