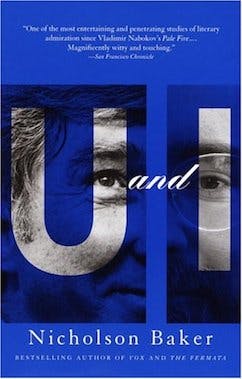

“On August 6, 1989, a Sunday, I lay back as usual with my feet up in a reclining deck chair padded with blood-dotted pillows in my father-in-law’s study in Berkeley (we were house-sitting) and arranged my keyboard, resting on an abridged dictionary, on my lap.” So begins Nicholson Baker’s tribute to John Updike, U and I: A True Story, a work of “autobiographical criticism.” As the opening sentence implies, this is not a typical work of criticism—it is as much about the act of writing as the thing he is ostensibly writing about.

Nearly 25 years after U and I’s publication, a new book by the young writer J.C. Hallman, B & Me: A True Story of Literary Arousal, aspires to do for Baker what Baker did for Updike. That a writer would one day come along and redirect the obsessive gaze of U and I’s self-described “closed-book examination” at its own architect was perhaps inevitable. Baker even cautions against the impulse: “I don’t want it to happen,” he frets midway through the book. “I don’t want to see the techniques of ‘closed-book examination’ applied to any other novelist. I want this essay to be the end of it.” Apparently that was wishful thinking.

But B & Me aspires to more than mere reiteration. Hallman, before embarking upon this volume, edited two anthologies on the subject of “creative criticism,” which he identifies as closely related—though he didn’t know it at the time—to the “autobiographical criticism” practiced by U and I. Baker’s book, it soon becomes clear to Hallman, “was firmly planted in the tradition” he had so exhaustively studied. U and I was an effort to grapple with an author from a vantage of candid inexpertise —of familiarity rather than mastery, of affection rather than erudition. Here Hallman has set out to take the next step.

“What needed to be done,” he reflects early on, “what no one had ever done, was tell the story of a literary relationship from its moment of conception.” In other words, this is a critical study that begins in total ignorance. When B & Me opens, Hallman knows hardly anything about Nicholson Baker—is only vaguely aware that he exists. Slowly he sidles up to the corpus, curious and eager, and records the fruits of his blossoming acquaintance. The book is thus in part about “the moment when you realize that there are writers out there in the world you need to read, so you read them.”

Or you try to read them. Hallman’s efforts are thwarted no sooner than he’s picked up U and I—and here we encounter the first of many excrescences with which B & Me is barnacled. “One night I opened it,” he describes. “I liked it … Then, for some reason, I stopped reading. The next night I started again—and stopped again. Because I liked it. This is what I happened. I clenched. Then I seized. I clenched and I seized.” Yes, well, that would be a problem. But is it a problem we need to hear about? Time and again B & Me veers away from its subject in order to entertain an unrelated thought or indulge an idle digression. This proves essential to the methodology. Hallman, it soon transpires, is a proponent of what he calls “creative criticism”: an approach that emphasizes “writers depicting their minds, their consciousness, as they think about literature.”

Creative criticism, as far as I can tell, is when a critic discloses what he had for lunch that afternoon or what the cat is up to while he’s hammering away on the keyboard. Of less interest to the creative critic, it seems, are niceties like research and intellectual rigor. The most distinctive feature of U and I was Baker’s refusal to consult the work he was writing about: He was quoting Updike from memory, and what he could remember, and in its own way what he could not, was the foundation of the “closed-book” study. B & Me doesn’t adhere to this restriction—its subject’s books remain at hand, searchable, citable, poised for scrutiny. Hallman finds himself irritated by the fallibility of Baker’s memory: “‘That’s insane,’ I said to myself, out loud, every time Baker tried and failed to remember another Updike passage.” And yet Hallman can’t seem to get Baker right even with his books open in front of him.

Of an episode involving the shame aroused by redeeming an elaborate fast-food promotion, Hallman says that Baker “got embarrassed while he was there—McDonald’s is an embarrassing place.” This is a bizarre mischaracterization of one of U and I’s most memorable scenes: Baker’s discomfort has nothing to do with McDonald’s being “an embarrassing place,” but rather is the product of a very specific exchange. Even the book's final pages are contorted by Hallman's retelling: He misattributes the last line to an anecdote mentioned ten pages earlier.

Nor are the inaccuracies confined to U and I. Indeed, Hallman can scarcely seem to mention one of Baker’s books without blundering. Speaking of a change in temperament he detects in a mid-career New Yorker essay, Hallman observes:” [this essay] is Baker’s first note of complaint.” Rather an odd claim, given a great deal of Baker’s first novel, The Mezzanine, has to do with the small pleasures no longer afforded to the world when our quotidian furnishings are meant to be improved but wind up appreciably diminished. Here he is on the replacement, in fast-food restaurants and corporate offices, of paper-towel dispensers with hot-air hand driers:

Is it, in fact, an efficient, environmentally upright user of the electricity produced by burning fossil fuels? No—there is no off button that would allow you to curtail the thirty-second dry time—you are forced to participate in waste … Is it quick? It is slow. Is it thorough? It is less thorough … Comes to your senses, world!

On Baker’s Vox Hallman fares no better. Of a sequence in which Abby, one of the novel’s two leads, describes a sexual fantasy she enjoyed the previous evening, Hallman says: “What had actually made her come was a pair of ideas ... but the conversation gets sidetracked before she ever gets to them. … That she fails to explain is important.” But she does not fail to explain. What made her come, she says, was the fantasy that men driving along a nearby highway could hear her “moaning exaggeratedly in the shower.” And yet not only did this explanation somehow elude Hallman, its apparent absence he maintains is “important.”

I might suggest at this point that Hallman is not the ideal candidate to write about Nicholson Baker. Though he certainly seems to think it’s his exclusive domain: The attempts of any other writer to hold forth on Baker he derides protectively. Particular contempt is reserved for Martin Amis, whose profile of Baker for the Independent on Sunday in 1992 Hallman admonishes as if it were an act of merciless character assassination. “I hated Amis,” he rumbles, nursing his animosity. So he swings back, even dragging the late Kingsley into the fray: “It must be awful to know that every woman you sleep with does so because she craves the seed of the truly great, now beyond reach, but which can perhaps be reconstituted from a watered-down specimen.”

Amis, in his very dry and very funny Baker profile, jokes that he “somehow found it necessary to pre-devastate Baker with the news that one of Vox’s supposed coinages (a synonym for masturbation) had been casually tossed out by me two novels ago.” When the coinage itself, “strum,” comes up in Hallman’s study, he can’t resist stealing it back for his charge. “Martin Amis’s claim over this word is completely false,” Hallman flatly declares. “It appears in none of the books Amis published in the twelve years leading up to Vox.” Ah, but it does: It appears in Money, from 1984. John Self, the narrator, fondly reminiscences to the reader that he’s “taken up handjobs again”: “Well,” he says, “here we all are, lying flat on our backs, strumming ourselves like bent Picasso guitars.”

As B & Me draws to a close, Hallman gets to wondering whether he’s been too hard on the author of The Information and London Fields. “Perhaps,” he sighs, “I should read Martin Amis.” One wonders, given his tenuous grasp of Baker, whether it would do him much good.