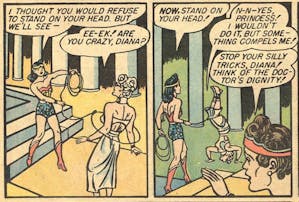

The first thing Wonder Woman ever does with her magic lasso is to play bondage games. This is in Wonder Woman #1, from 1942. Wonder Woman's mother, Queen Hippolyte of the Amazons, gives her daughter the lasso as a gift, explaining, “The magic lasso carries Aphrodite's power to make men and women submit to your will! Whomever you bind with that lasso must obey you!” Just then, an Amazon doctor walks in, and Wonder Woman—aka Diana Prince—decides to try out her new toy. She lassos the doctor and commands, “Now stand on your head!” The hapless doctor declares, “N-n-yes, princess! I wouldn't do it, but something compels me!”

You can see where Wonder Woman is coming from. If you had a magic lasso, wouldn't you want to make dignified doctors stand on their heads? But, alas, there aren't many such hijinks in the new Sensation Comics Featuring Wonder Woman Vol. 1, an anthology of one-off Wonder Woman stories by a variety of creators, many of whom aren't DC Comics regulars. It's meant to be eclectic and fun and unstructured; the stories aren't strictly in DC continuity, which means creators have more leeway for invention than in regular titles. And yet, despite the greater freedom, Wonder Woman never gets to play with her magic lasso the way she did in that first issue.

That's because over the years, Wonder Woman's magic lasso has been depowered. In the original comics by the psychologist, polyamorist, and crank William Marston and artist Harry Peter, the lasso compelled obedience. Gradually, though, it was depowered until it only compelled truth—a transition solidified in the popular '70s television show starring Lynda Carter. Instead of being able to make anyone do anything, the lasso now just makes folks answer honestly—which is a lot less useful, and, not coincidentally, a lot less entertaining. In the first story in Sensation Comics, by writer Gail Simone and artists Ethan Van Sciver and Marcelo Di Chiara, Wonder Woman ties up all of Batman's villains with her rope and forces them to confront their deepest fears. In Gilbert Hernandez's “No Chains Can Hold Her,” a broad-shouldered, very Amazonian-looking Wonder Woman lassos robots and cheerfully bashes them against the ceiling. In Amanda Deibert and Cat Staggs' “Defender of Truth,” she trusses up some hunky centaurs. But nowhere in the book does Wonder Woman command anyone to stand on his (or her) head. The lasso doesn't have that power any more.

That change in power may seem like a minor fannish detail—no more important than the fact that Superman originally had the power of superjumping rather than superflight. But the magic lasso of command was absolutely central to the original Wonder Woman stories, and to Marston's original vision of the character. Marston described the lasso as “symbol of female charm, allure, oomph, attraction,” and of the power that “every woman has … over people of both sexes.” In his (very idiosyncratic) psychological writings, Marston, who believed women were destined to rule over a peaceful matriarchy, talked very explicitly about women's “oomph” as sexual; in his academic writing, he described intercourse as the vagina engulfing and controlling the penis. The lasso, then, was supposed to be a yonic symbol—and the use of the lasso was intended to be a form of erotic play. The original Wonder Woman comics were structured around Wonder Woman tying up and controlling bad guys (male and female; Marston enthusiastically endorsed lesbianism) and then being tied up and controlled in turn. The comics weren't centered on violent battle, but on bondage play. Marston wanted boys and girls of all ages to learn the joys of submission to a good woman—to find out how much fun it is to be stood on your head and then, maybe, how much fun it is to switch and make that princess/mistress stand on her head herself.

This isn't how superhero narratives usually work. Henry Cavill and Scarlett Johansson may provide eye candy onscreen, but the main driver of Man of Steel or The Avengers is fisticuffs. It's hardly a surprise that images for Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman in the upcoming Batman v. Superman film show her carrying not a lasso, but a sword. Director Zach Snyder knows you're in the theater to see hacking and hitting—the money shot involves violence, not kink.

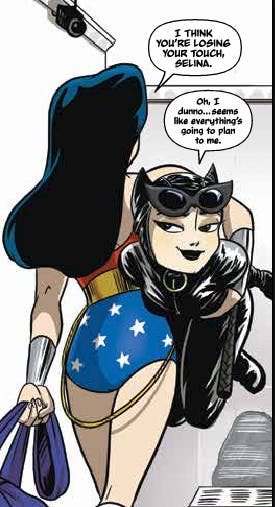

And that's how most of the Wonder Woman stories in Sensation Comics work, too. There are a couple of exceptions. In Ollie Masters and Amy Mebberson's “Morning Coffee” for example, Catwoman (in full skin-tight cat-suit) sports a knowing grin as she's carried away under Wonder Woman's arm—a flirtatious scene that Marston would surely approve of.

But Gilbert Hernandez's story is more typical, with Wonder Woman, Supergirl, and Mary Marvel cheerfully beating the tar out of each other. Corina Bechko and Gabriel Hardman's “Dig for Fire” places Wonder Woman in an alternate totalitarian dimension fighting the evil Darkseid. When Marston wrote about totalitarian societies (like the Mole-Men or Seal-Men), he'd always have Wonder Woman free the enslaved women, who would then be installed as loving matriarchal rulers over their former oppressors; a bondage switch as utopian dream. “Dig for Fire” though, ends with an explosion and an execution—default superhero-genre violence, in other words.

Wonder Woman was initially, and deliberately, designed to challenge that default. “It seemed to me, from a psychological angle, that the comics' worst offense was their blood-curdling masculinity,” Marston said in a 1944 essay for the American Scholar. Wonder Woman's lasso was his answer to all that blood-curdling—a way to give Wonder Woman a supertool which could weaponize erotic persuasion. The Wonder Woman comics were meant to be a radical challenge to patriarchal storytelling—and some 70 years later, they still are. Rather than the strongest man winning through violence, Marston imagined a world in which the strongest women triumphed through erotic oomph, compelling a peaceful utopian matriarchy for all.

Again, Marston was a crank, and it's not really a surprise that his particular ideas about gender essentialism and the utopian power of bondage haven't been popular with other creators. But still, it feels like something's been lost when radical utopian matriarchal kink is turned into plain old violence. It's worth remembering that in the beginning, Wonder Woman carried not a sword but a lasso, and used it to turn the superhero genre on its head.