The night Mamoru Samuragochi lost his hearing completely, he had a dream. “I was sitting on a beach at night, alone, holding my knees,” he wrote in his 2007 autobiography, Symphony No. 1. He stood and walked into the sea until the water came up to his neck. All he could hear was the sound of waves crashing on the shore. “At that moment, something grabbed my ankles and started pulling me under.” He struggled to swim to the surface but kept sinking. “The sound became smaller and smaller as the water entered my ears,” he wrote. “All of a sudden I couldn’t breathe anymore, and I lost consciousness. It was then that I woke up.”

He got out of bed, walked over to his keyboard, and laid his fingers on the keys. He heard nothing. “I realized the keyboard wasn’t on,” he wrote. “I thanked God.” He switched it on, held his breath, and struck the keys again. “The result was the same.” Silence. He started to panic. He paced the room, smashed his ears with his fists, and slammed his head against the wall. When he finally came to, he found himself in a puddle of blood—somehow he had torn his knee to the bone. “But nothing mattered,” he wrote.

Then Samuragochi got an idea. The tinnitus inside his skull maintained a steady pitch, like a tuning fork. He grabbed a blank sheet of staff paper. His favorite Beethoven piece, the “Moonlight Sonata,” played in his head, and he scribbled it down from memory. He then found the original sheet music and laid the two pieces of paper side by side. They were identical, note for note. Samuragochi wept. Even if he couldn’t hear, he could keep composing.

This story would become the foundation of the Samuragochi legend. In 2001,Time magazine dubbed him a “digital-age Beethoven.” He played piano for the magazine’s reporter, whose eyes, he said, welled with tears. Samuragochi told Time, “Losing my hearing was a gift from God.”

That same year, Samuragochi began work on his first symphony. Then one day, he felt a sharp pain in his wrist. “That’s when I realized I could not play piano anymore,” he wrote in Symphony No. 1. “I was shaking with anger, screaming in the studio, and I couldn’t even hear my voice screaming.” His tinnitus intensified, becoming a 24-hour intracranial roar, “as if I was trapped in a boiler room.” He had seizures, during which “it was rare that I didn’t urinate,” he wrote. “The sacred music room became a frightening battlefield of vomit and piss and blood.” Finally, in the fall of 2003, he finished the symphony. “Immediately after, I tried to kill myself.”

In 2008 his hometown of Hiroshima selected the symphony to be performed at a ceremony commemorating the bombing of the city in World War II. The time and place were particularly meaningful to Samuragochi. On August 6, 1945, his parents had been within two miles of the nuclear explosion. His father, a rice deliveryman, was covered in the “black rain” of nuclear fallout, Samuragochi wrote. Doctors could never explain the reasons for Samuragochi’s hearing loss, but “some said they couldn’t rule out a genetic handicap as a second generation atomic bomb victim,” he wrote. “The blood of the atomic bomb itself now runs through my body.”

After the performance, Samuragochi would be hailed as one of the great classical talents of his generation. Japanese media seized on Samuragochi’s spectacular story, featuring him on TV specials and in magazine articles. CD sales of the symphony by Nippon Columbia, one of Japan’s oldest and most respected record labels, eventually climbed to 180,000—a blockbuster for the Japanese classical music industry, which had been struggling to attract new listeners. When Recording Arts magazine asked readers to name their 20 favorite classical CDs of 2011, Samuragochi was the only living composer on the list. In the summer of 2013, his publisher released a paperback version of his autobiography with a cover blurb from the legendary writer Hiroyuki Itsuki: “If there is an artist whom we can call a genius today, Mamoru Samuragochi would definitely be the one.” After decades of struggle, Samuragochi was finally receiving the recognition he’d always craved.

It wouldn’t last. On February 2, 2014, his former manager Minoru Kurimura was in a meeting when, feeling bored, he pulled out his iPhone and checked his email. He saw a message from Samuragochi. “I’m human filth,” he wrote. “I have betrayed you to an extent I can never fully repay. I offer my deepest apologies.” The Samuragochi story was, it turned out, a lie. Within days, nearly every detail of the deaf composer genius narrative would be called into question. Kurimura read on: “I have embroiled you in a terrible quandary of my own making. I am prepared for death.”

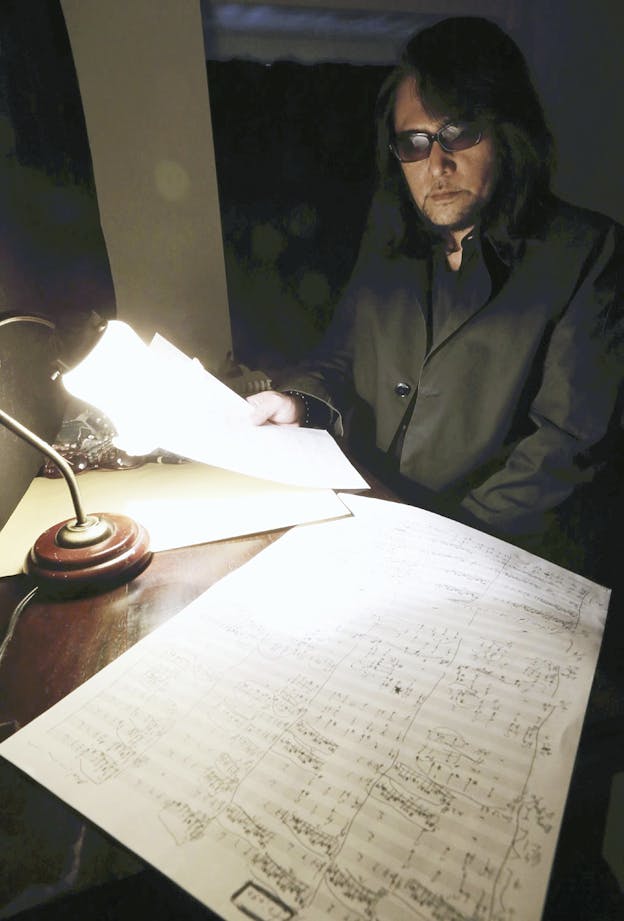

On a summer afternoon in 1996, Samuragochi went to a coffee shop in Shibuya, an upscale district in Central Tokyo, with a business proposal for Takashi Niigaki, a young music teacher who’d been introduced by a mutual friend. From the moment they shook hands, it was clear the two men were opposites. Born in Hiroshima in 1963, Samuragochi moved to Tokyo as a teenager and fronted a rock band, but abandoned the stage after his younger brother died in a car crash. He turned instead to composing, and in 1993 began to write scores for television and film. Samuragochi was intense—he told Niigaki he “subsisted without food”—and almost absurdly confident, saying he was famous in his field. He wore black, and his dark hair fell past his broad shoulders. “In a word,” Niigaki recalled, “heavy metal.”

Niigaki, meanwhile, was a specimen of Japan’s music education system. Unmarried and still living with his parents, the then-25-year-old dressed conservatively and mumbled without making eye contact. Born in Tokyo, he first sat down at a piano when he was four years old. His older brother Shigeru remembers him refusing to come outside and play so he could practice piano at home. By age eight, Niigaki was composing his own short pieces. He had an epiphany when he saw Star Wars. “That was the first time I felt the joy of orchestrated music,” he told me. After he heard one of John Cage’s “prepared piano” works on a radio show, his tastes skewed experimental and came to include everything from Baroque to jazz to pop.

For college, Niigaki attended the Toho Gakuen School of Music, the alma mater of the renowned conductor Seiji Ozawa, and stayed on after graduation to teach composition. His students loved their soft-spoken teacher, a gentle savant with an encyclopedic knowledge of classical music. Most lecturers, when discussing a composition, would hand out photocopied sheets of music to students; Niigaki would write on the chalkboard from memory.

Outside of class, Niigaki wrote his own music, and soon became known in Tokyo composer circles for his virtuosic, often kooky pieces. (One featured dueling vacuum cleaners.) He didn’t own a TV, computer, or cell phone. When he composed, instead of using software, he wrote the music out by hand, his distinctive, angular notes slashing across the staff.

“In the centuries of music I’d studied, I wanted to be seen as standing at the forefront,” Niigaki told me. “The Bachs, the Beethovens, the Mozarts—I wanted my name to be the last one in line.” But whereas some composers had a knack for self-promotion, Niigaki lacked bravado. “He’s a man who avoids the spotlight at all costs,” said Kenichi Nishizawa, a composer friend of Niigaki. For fun, Niigaki would invite friends over to his place for beers and they’d listen to old cassette tapes, competing to guess the composer and the year of composition. Niigaki always won. “I don’t think he’s really capable of doing anything besides writing music,” said his friend Takafumi Suzuki, a music critic in Tokyo.

Over coffee in Shibuya, Samuragochi told Niigaki he’d been hired to compose the score for a small film about an AIDS patient who faces discrimination, and he needed help with the orchestration. For composers, this was a common request, as breaking down a piece into parts for each instrument can be painstaking work. Samuragochi handed him a tape of his own music, to give Niigaki a sense of his style. It featured Tibetan monks chanting over a rhythm track. “It was rudimentary, to be kind,” Niigaki remembered.

Samuragochi was no Mozart, but he had managed to get the soundtrack job, which was more than Niigaki had ever done. Plus, Niigaki had always had difficulty saying no. He took the job.

Ever since Japan began to open its ports to the outside world in 1868, the country has embraced Western classical music. At first, conductors and musicians strived to copy European performance as faithfully as possible. Western classical music receded in the nationalist fervor of World War II, then returned in the post-war years. But by then, tastemakers had moved on from Romantic music and were deep into the vertiginous experimentation of composers like Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and György Ligeti. Japan produced its maestros: Toru Takemitsu, best known for scoring films by Akira Kurosawa, borrowed from both European and Japanese traditions, while Ozawa became one of the world’s top conductors. But the country never had a great Romantic composer. There was no Japanese Beethoven. Samuragochi made no secret of his ambition. He may have lacked formal training, but he aspired to nothing less than the resurrection of Romantic tonal music.

Samuragochi gave Niigaki a demo tape as guidance for the film score. It turned out orchestration was only part of the job. Some of the tracks, recorded at home on Samuragochi’s synthesizer, were complete; others were sketches that Niigaki would have to rework entirely. Two months later, Niigaki sent the finished piece back to Samuragochi. “He was very, very pleased,” Niigaki said.

At the end of the recording process, Samuragochi told Niigaki that, unfortunately, he would not be credited for the score. Niigaki was disappointed, but he deferred to Samuragochi. It wasn’t the first time a composer had hogged credit for the work of an underling, and Niigaki was grateful for the chance to write for an orchestra.

Six months later, the phone rang. Samuragochi had landed another job, the soundtrack for a video game in the Resident Evil series, and he needed Niigaki’s help. The catch: They had only ten days to complete it. But there was a determination—in retrospect, a desperation—in Samuragochi’s voice, and a presumption of inevitability. Samuragochi had already lined everything up: He’d even persuaded the producers at the gaming giant Capcom to spring for an orchestra. Now he needed Niigaki. “It wasn’t a question of maybe,” Niigaki recalled.

If video games seem like a strange outlet for an aspiring composer, you didn’t grow up in Japan. Some of the most popular Japanese music of the last few decades originated in video games and anime cartoons. The soundtracks to several Final Fantasy games have reached the top 10 on the Japanese charts. In the 1980s, boys flocked to concert halls to hear orchestras perform music from the game Dragon Quest. Legend has it their thumbs danced over invisible controllers as they listened.

Niigaki frantically threw together dozens of short pieces for the game, soliciting help from composer friends to complete the project on time. Samuragochi once brought Niigaki to a meeting with Capcom producers and introduced Niigaki as his assistant. Whenever the Capcom producers had a technical question about the music, Samuragochi would defer to Niigaki. Again, Samuragochi received full credit for the score.

By the time Samuragochi called back in early 1999, Niigaki knew the routine. “When he calls, everything’s already ordered and assigned, deadline and everything,” Niigaki said. “There’s no way out.” Niigaki’s friends described him as well-meaning but submissive, accommodating to the point of spinelessness. “If somebody is pushy, he’s going to be the first to back down,” said Suzuki. “Samuragochi is not a man he could say no to.”

The new project was their most ambitious yet. Capcom had hired Samuragochi to compose 20 minutes of music for Onimusha, a role-playing game for PlayStation 2, and he had arranged for a 205-piece orchestra to perform at the press conference announcing the game—a rare splurge for a video-game soundtrack. Samuragochi’s creative contribution was minimal, according to Niigaki: He recorded an eight-bar phrase on his synthesizer, which would become the game’s fanfare-like battle theme, and a passage featuring bamboo flute and drums.

While they were working on Onimusha, Samuragochi told Niigaki that he was having hearing problems. “I remember telling him I was so sorry,” Niigaki said. But they continued to converse normally, as though Samuragochi could hear him perfectly well. According to Niigaki, Samuragochi soon told him that he was doubling down on deafness: From then on, he would pretend that he couldn’t hear anything at all. “The reason is clear,” Niigaki said, looking back: With the Onimusha press conference, Samuragochi was coming out as a public figure, but he still couldn’t write music. If he pretended to be deaf, he could avoid answering questions.

But the orchestra posed a problem. A conductor often needs to confer with the composer of a new piece of music, so Samuragochi recommended that Capcom hire Niigaki to lead the orchestra. During rehearsals, when a question arose, Niigaki would pretend to consult Samuragochi. “I would go over to him and point to the score so he could nod,” Niigaki said.

Niigaki was deeply uncomfortable abetting Samuragochi’s lie. But he was thrilled to be conducting his own music—“I had the best seat,” he said—and the concert at the press conference drew praise. “I never expect to experience anything that magnificent again in my life,” Niigaki said.

As the release date of the Onimusha soundtrack approached, Samuragochi asked Niigaki if he, as conductor, would be willing to write a short essay for the CD liner notes. “Praise me the way you wish your own music would be praised,” Samuragochi told him. Niigaki wrote a paragraph describing the music in kind but plain terms. He sent the draft to Samuragochi, who asked if he could make some modifications.

When the liner notes finally appeared in print, Niigaki saw that Samuragochi had made more than a few changes. The title now read: “Witness a Miracle.” The development of the theme in the second section was “an act of God,” the climax in the third movement “a work of genius.” The author of the essay, “Niigaki,” then recounted watching Samuragochi compose the piece in a fit of creative madness, “almost like he was possessed.”

When Niigaki saw the essay printed under his name, he was “profoundly embarrassed,” he told me. “My face turned red.” Niigaki was now on the record as part of the lie.

Still, that wasn’t what flustered Niigaki most. The liner notes contained an even more disturbing passage: “Mamoru Samuragochi is currently working on his first symphony.”

If Samuragochi was not in fact deaf, he certainly committed to the act. He turned off the audio function on his phone, communicating only by text and email. He learned sign language, and used an interpreter during interviews and public appearances. He took to wearing sunglasses, which he claimed helped ease his tinnitus.

After Onimusha, Niigaki assumed that the truth would come out at any moment. “All the evidence was there for anyone who wanted to look,” he said. Niigaki told only one person, his friend Suzuki, and focused on the positive. “I saw it as a chance to test my abilities,” he said. It also gave him access to a mass audience, which few living composers ever get. Niigaki was by now a fixture of Tokyo’s contemporary music scene, but his pieces targeted the in-crowd. Writing for Samuragochi—writing as Samuragochi—gave him a new identity as a composer, and unlocked a fresh musical vocabulary.

When Samuragochi asked Niigaki to compose a 70-minute symphony, Niigaki was stunned. “I didn’t think it was possible,” he said. The longest piece Niigaki had ever composed was 20 minutes, and Samuragochi wanted the symphony within a year. Niigaki also faced a new conundrum: This wasn’t another commercial gig for an audience of gamers. He would now be creating music for the classical world. He would be deceiving his own.

Samuragochi communicated his vision to Niigaki on a single sheet of white paper covered edge-to-edge with scribblings: exhortations followed by multiple exclamation points, diagrams tracing dynamics, and flowery descriptions of sound. “Only compose music the value of which will last into the future!” he wrote at the top. He mapped out the symphony’s four themes, which he called “Prayer,” “Ascension,” “Suffering,” and “Chaos.” The piece should begin with a Gregorian chant, “which is the origin of Western music,” and then trace its evolution from the polyphony of the Middle Ages to Bach. The “Prayer” section should sound like William Byrd’s “Missa” and Victoria’s “Requiem.” “All the sadness has to be expressed in the ‘Prayer’ section,” he wrote. “Suffering” should recall the style of Mozart’s “Requiem” or Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana.” Samuragochi added a note at the end that fairly summed up his philosophy: “There’s no rule you cannot break to achieve a better result.”

Niigaki didn’t think much of Samuragochi’s guidelines. “That’s not how you make music,” he told me. In his autobiography, Samuragochi wrote: “Music, if it’s meant to support people who are suffering, can only be created by someone who has suffered more than anybody else.” But for Niigaki, composing the symphony wasn’t a matter of digging into his soul. It was about using a set of musical tools, developed over centuries, to conjure those feelings. The experience of suffering itself, he said, is “completely unnecessary.”

In Niigaki’s telling, he simply built on the “Samuragochi sound” he’d developed during their previous projects: dark, melodic, bombastic. While Niigaki was busy composing, Samuragochi was emailing Kurimura, his manager, narrating his daily creative struggle. In retrospect, Kurimura said, it reminds him of A Beautiful Mind: “I think he really thought he was composing.”

When the symphony finally came out, critics would note its similarities to Mahler, Bruckner, and other late-Romantic heavies. The final section in particular, they said, was an obvious homage to—or a rip-off of—Mahler’s Third Symphony. It amused Niigaki to hear people make this comparison. “That’s not Mahler,” he told me. It’s a reference to the theme song of “Space Battleship Yamato,” a classic anime series from 1974. It was an important allusion, Niigaki argued, as it reflected his catholic, music-is-music philosophy of composition. Samuragochi always insisted that his music be gloomier. “That was his request, that it sound tortured,” Niigaki said. The fact that his masterpiece contains a blatant anime reference would probably sail over his head: “I don’t think he’d get it.” Though Niigaki would never mock Samuragochi to his face, he was doing it through the music.

Niigaki finished the symphony in 2003 and tried to forget about it. Kurimura remembers Samuragochi saying the piece “would not be played during my lifetime.” “It’s not going to make any money,” Samuragochi told him, “but I have to try it.” In the meantime, Samuragochi commissioned other, smaller pieces—string quartets, piano sonatas—which Niigaki continued to deliver. But the symphony haunted him. He was torn between wanting it released and knowing how painful it would be to see someone else take credit for a year’s labor. It was like giving one’s child up for adoption, he said. He also knew that once the symphony went public, their lie could only last so long.

Samuragochi proved to be as much a virtuoso at marketing as Niigaki was at composing. While Niigaki made music, Samuragochi wrote and published his autobiography, pitched his story to TV networks, and tried to drum up interest in the finished symphony. His salesmanship revolved around the theme of suffering—a ripe subject in Japan, where disabled people are treated with a certain guilty deference; where survivors of the bombing in Hiroshima, known as hibakusha, enjoy saintlike status; where natural disasters regularly ravage the country’s infrastructure. Samuragochi built up his suffering bona fides whenever possible, visiting community centers for handicapped children, taking photographs, and displaying them in his living room for the benefit of journalists. Between his apparent deafness, his background as a child of Hiroshima victims, and the endorsements of authoritative voices like Hiroyuki Itsuki and Time magazine, no one dared question the Samuragochi myth.

In 2008, Samuragochi contacted Niigaki with some good news: The Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra had selected his opus to be performed at a G-8 ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the blast. The symphony had originally been called “Celebration of Today,” but Samuragochi had renamed it “Hiroshima,” which likely contributed to its selection. (Composers have long known the marketing power of tragedy: Krzysztof Penderecki changed the title of his ear-piercing “ 8′37″ ” to “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.”) Niigaki felt only dread: “That which must not happen had happened,” he told me. “This ghost that I’d cast into the shadows had returned.”

Word of the deaf genius second-generation atomic bomb victim composer eventually reached Nippon Columbia, which signed on to record the “Hiroshima” symphony. It was then that Niigaki tried to sabotage Samuragochi for the first time. He dispatched his friend Suzuki to tell a producer at the record label that Samuragochi had a collaborator. “The truth needed to be shared,” Niigaki told me. But nothing happened. Two years later, Nippon Columbia received another tip, this time from a former Capcom employee, who said that Samuragochi used an assistant. He, too, was ignored.

The recording sessions in April 2011 were emotional. A month earlier, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake off the east coast of Japan generated a tsunami that killed more than 15,000 people, and destroyed the nuclear reactor in Fukushima. The symphony recorded over those days would become an anthem and a source of hope for the victims.

Despite his reservations, Niigaki continued to compose, and Samuragochi ramped up the PR. One day in 2008, Samuragochi saw a young girl on TV named Miku Okubo, who played piano and violin despite having only one arm. He wrote her a letter and decided to start composing for her. With his backing, Okubo became a minor celebrity, featured on TV and playing regular gigs at concert halls, and the subject of a full-length book. Samuragochi described their relationship as that of “master and apprentice,” and Okubo’s family warmed to him. “He seemed like a kind, delicate man,” her father told reporters later. (The Okubo family declined to be interviewed for this article.) By pure coincidence, the Okubos knew Niigaki separately: He had been accompanying their daughter on piano during violin performances since she was four. But they had no idea that Niigaki was actually writing the music Samuragochi gave her.

In 2012, after the “Hiroshima” symphony became a surprise hit, Samuragochi told Niigaki that the national network NHK would be shooting a documentary about him. Samuragochi was to compose a new piece for the victims of the tsunami in northern Japan, and the filmmakers would document his creative process. Samuragochi imposed one ground rule: He would not let them film him writing music. “The process is sacred,” he told the director.

As usual, Samuragochi gave Niigaki a tight deadline—he had two months to compose a ten-minute “Requiem for Piano.” Complicating things further, Niigaki would have to deliver the piece while the documentary was being filmed. Since Samuragochi would have a camera crew trailing him 24/7, he asked Niigaki to send the sheet music to his house by courier using a fake name. He reminded Niigaki to use generic, unidentifiable notations and to include blank sheets of music paper, for the “before” shots. Samuragochi wrote in a text message: “It’s an important piece that is going to be played at the end of the NHK special, showing that the genius composer went through hell to compose a song for the victims.”

Meanwhile, Samuragochi was pretending to go through hell. During the filming, he “met” a young girl named Minami—she was pre-screened by the producers—whose mother died in the tsunami, and dedicated the requiem to her. For inspiration, he sat alone on the beach where the girl’s mother disappeared, “so that the spirits of the victims come down to him,” according to the film’s narrator. Later, back at his house, he writhed in bed, groaned from the supposed pain of his tinnitus, swallowed dozens of white pills, and crawled around on the floor, apparently too weak to stand. Finally, Samuragochi stumbled into the living room. “It’s finished,” he said. He then disappeared into his study. Twelve hours later, he emerged with the complete score. The camera lingered over the perfectly shaped notes.

The documentary aired in March 2013 and reached millions of viewers. When Niigaki saw it, he was dismayed. He picked up a copy of Samuragochi’s autobiography, just reissued in paperback, and discovered episodes from his own musical training, retold as if they were Samuragochi’s. “It read as farce,” he told me. Enough was enough. “It’s dangerous to keep doing what we’re doing,” Niigaki wrote in a text message to Samuragochi. “I think it would be smart to stop after the current tour is over.” Samuragochi responded immediately, asking to meet. The next day, Niigaki went to Samuragochi’s house in Yokohama. They sat down, and Samuragochi handed Niigaki a letter. “This is from my wife,” he said. In the letter, she begged Niigaki not to reveal the secret, suggesting that if he did, she and Samuragochi would kill themselves. Samuragochi then laid his head at Niigaki’s feet, begging him to continue. When Niigaki still hesitated, Samuragochi pressed an envelope with 1 million yen into his hand. This envelope brought the amount of money Samuragochi had paid Niigaki—for more than 20 pieces over 18 years—to 7 million yen, or about $60,000. Niigaki relented. He would continue to compose.

In October 2013, Niigaki went to a bookstore and picked up the newest issue of the literary magazine Shincho 45, which featured an article titled, “ ‘Totally Deaf Genius Composer’ Mamoru Samuragochi—Is He Real?” In it, the music critic Takeo Noguchi questioned the entire Samuragochi spectacle, from his tortured creative process to his deafness. Noguchi didn’t have any inside sources: He’d simply listened to the music, watched the TV programs, read the autobiography, and concluded that Samuragochi was a con artist.

“The word is out,” Niigaki told Samuragochi and suggested once again that they disband. But the article didn’t garner much attention. Samuragochi, who was just beginning to enjoy his long-sought fame, dismissed Niigaki’s concerns.

Tensions were also escalating between Samuragochi and the Okubo family. Okubo had declined to participate in a concert for the NHK documentary, enraging Samuragochi. After that, he kept making new, increasingly strange demands. In the run-up to a concert in the fall of 2013, Samuragochi told Okubo to walk onstage with her prosthetic arm detached, then attach it before playing. Okubo refused. If she was serious about violin, he said, she had to quit her school’s ping-pong club. “He’s very good at reading people’s minds,” Okubo’s father told reporters later. “He knows how to exploit your weak points, and how to make you feel good.” In October, Samuragochi sent the 13-year-old Okubo an email delivering an ultimatum: Either quit ping-pong and devote her life to a career supported by “Mamoru-san”; or give up her dream of becoming a professional violinist. “Make your choice. It’s your life,” he wrote. Okubo replied that she would continue studying violin without his help.

Niigaki, meanwhile, was avoiding Samuragochi. Yes, he’d agreed to keep up their collaboration at Samuragochi’s pleading, but now he hoped silence would make him go away. Samuragochi would not be ignored. In a series of increasingly panicked emails, he begged Niigaki for a meeting. “Please give me five minutes at our house in Yokohama.” “I’m really shocked that you’re not responding.” “You obviously changed your phone number.” He threatened to show up at Niigaki’s office at school. “This is my final suggestion,” Samuragochi wrote on December 8. “Before [my wife and I] commit suicide, I’m going to write a letter telling the truth about our 18-year collaboration.”

Niigaki started getting emails from their mutual friends, who he suspected were reaching out on Samuragochi’s behalf. One of them was from Okubo’s mother, asking him to return some sheet music from a recent recital in which he’d accompanied her daughter. When he didn’t reply, she sent a follow-up, mentioning off-hand that Okubo had quit music school. Startled, Niigaki replied to ask why, and Okubo’s mother explained that they’d had a falling out with Samuragochi.

This, Niigaki later said, was the moment he decided to quit for good. He’d always reassured himself that his collaboration with Samuragochi was a victimless crime. They were lying, but they were making quality music that people enjoyed. Now he understood that Samuragochi was hurting people, and Niigaki was enabling him. “If I stayed silent now, I’d stay silent forever,” Niigaki told me. He emailed Okubo’s mother back, suggesting they talk in person.

They met at a coffee shop near the Okubos’ house, and Niigaki told the story of his relationship with Samuragochi. To prove it, he pulled from his briefcase an order sheet Samuragochi had given him, requesting a short piano piece. “They were shocked, of course,” he said. But it wasn’t clear how they wanted to handle this information until a few weeks later, when the father called Niigaki and said, “There’s someone we’d like you to meet.”

Every country has its own theater of apology, but Japan has elevated the form to an art. Company executives routinely apologize to the public for everything from product recalls to a bad fiscal year. In April 2014, a Japanese stem cell researcher wiped away tears as she apologized to a roomful of journalists after being accused of plagiarizing and fabricating data in two high-profile papers published in the journal Nature. (Her supervisor hanged himself.) A Japanese politician’s apology for misusing public money went viral in July after he cried hysterically during a three-hour press conference.

On February 6, 2014, Niigaki stepped in front of a thicket of microphones at the Hotel New Otani in Tokyo. He was visibly, almost comically nervous, staring down at his prepared statement as more than a hundred journalists waited to take down his words. This hadn’t been his idea. Niigaki would have preferred the slow fade—tell people that Samuragochi’s health had declined and he could no longer compose. “We’d gotten there through fiction, I thought maybe we could get out through fiction,” Niigaki told me. But when the Okubo family introduced him to Norio Koyama, a journalist for the tabloid newspaper Weekly Bunshun, and Koyama pushed Niigaki to go public, Niigaki found himself once again unable to say no.

Now here was Niigaki, sweating in his gray suit. “Ever since I met Mamoru Samuragochi eighteen years ago, I’ve been composing music for him,” Niigaki began, camera flashes popping as he spoke. “Even though I knew he was lying to the world, I agreed to compose for him, so I too am a co-criminal.” The press conference followed the typical script: confession, self-flagellation, submission to judgment. Niigaki’s complex reasons for revealing the lie were boiled down to the media-friendly explanation that the figure skater Daisuke Takahashi had selected the “Sonatina for Violin” for his performance at the Sochi Olympics, and Niigaki didn’t want him to be hurt by the deception. The presser concluded with a video of Okubo playing the violin while Niigaki accompanied her on piano—a performance organized by Koyama two days earlier—suggesting that the two real musicians were now out from under Samuragochi’s malevolent sway.

The Japanese media flayed Samuragochi with the same gusto with which they had built him up. Koyama’s Weekly Bunshun investigation led the coverage with the blaring headline, “Totally Deaf Composer Was a Con Man; Ghostwriter Apologizes and Reveals His Real Name.” The paper described Samuragochi’s past attempts at fame, including a small role in a gangster movie, and old acquaintances came forward to bash him. “The only thing he put his heart into was deceiving people,” said Mondo Okura, a producer who worked with him in his rock band days. Samuragochi’s mother-in-law compared him to the cult leader who orchestrated the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway.

The companies that abetted the lie hastened to distance themselves from Samuragochi. Nippon Columbia issued a statement saying it was “appalled and deeply indignant”—even though they’d twice received warnings about Samuragochi—and would no longer sell his CDs. Capcom also apologized and claimed ignorance, though Weekly Bunshun quoted a source saying that it was an open secret within the company that Samuragochi could hear. NHK aired a segment apologizing for failing to catch Samuragochi’s lie, and the director of the NHK documentary went into hiding. A nationwide tour was truncated, and an upcoming performance in New York City was canceled.

Niigaki resigned from Toho Gakuen, but otherwise he was enjoying his new life in the open. His piano performances drew bigger crowds than ever. He recorded an album with the free jazz musician Ryuichi Yoshida. He went on television to talk about the Samuragochi saga and to plug his own work. One program showed him visiting the home of the girl whose mother had died in the tsunami, to apologize for what he and Samuragochi had done. Her grandmother bid him farewell in front of the cameras: “I wish you the best. Don’t hide, be proud.” At the end of 2014, some of Japan’s year-in-review TV shows featured Niigaki riffing on piano and, in one case, jamming on guitar with a popular metal band. Niigaki was playing the fame game, and playing it well.

A few weeks after Niigaki’s press conference, Samuragochi hosted his own. He appeared transformed—clean shaven, hair cut short, trademark sunglasses gone—and apologized to his listeners, his publisher, NHK, Nippon Columbia, his tour organizers, the figure skater Takahashi, and the girl who lost her mother in the tsunami. (He did not include Okubo.) Then he vanished. He changed his email address and phone number and cut off everyone but a small handful of trusted friends. Reporters would congregate in the lobby of his apartment building in Yokohama, hoping to catch a glimpse of him. A furtive photo of Samuragochi taken on the subway went viral. Last July, I visited his building and pushed the buzzer. No one answered.

So I was surprised when, in January, he agreed to an interview—his first with international media since the press conference. He met me and my translator, David, at the door of his flat, bowing and greeting us by name. We walked into his dining room, a documentary crew trailing behind. (He would speak to me only on condition that it be filmed.) A row of sunglasses were lined up on the kitchen counter. Samuragochi’s hair had grown back to near-shoulder length, a few strands of gray among the black, and his beard had returned. He asked permission to dim the lights—his eyes are sensitive, he said—and his wife, Kaori, brought coffee. “Today,” he said, “for the first time, I’d like to present my side of the story.”

The last year had been painful, he said. “Eighty percent of my waking hours are spent in genuflection, regret, and apology.” He rarely goes outside, passing all his time in the small apartment with his wife and his cat, Minokichi, named after a bug character from Onimusha. He doesn’t watch television, but he seemed well aware of the judgment of the outside world.

Samuragochi did not dispute individual facts so much as the entire media narrative. Niigaki was the true genius, the story now went, cruelly exploited by Samuragochi, a man so callous and manipulative that he faked a disability.

This was all wrong, Samuragochi explained. Yes, he had hired Niigaki to help write his music, but Niigaki wasn’t being exploited. He was simply working for pay. It was a collaboration, Samuragochi said, and the music originated in his head; Niigaki was merely an “exceptional technician.” He insisted that over the years, he had provided Niigaki with numerous tapes recorded on his synthesizer to supplement the instructional diagrams. I asked Samuragochi if he could play me any of these tapes. Unfortunately, he said, he had destroyed them, since they were evidence of the illicit partnership. Then what about the instruments he’d used to record the tapes? He said he had thrown away his keyboards when he moved into the new apartment three years ago. “At this point,” he said, “all I can do is ask you to believe.”

Samuragochi also insisted that, although he had recovered some hearing in recent years, he was still deaf, at least partially. He pulled out a printout of the results of a hearing exam and pointed to one line: “Right ear, 40 decibels. Left ear, 60 decibels.” (A typical conversation in a quiet room is roughly 60 decibels.) I asked what our voices sounded like at that moment. As I spoke, he trained his eyes on Kaori, who listened to David’s interpretation and translated the question into Japanese sign language. “Something like this”—Samuragochi rapped his knuckles on the table—“I can hear,” he said. His hearing trouble was important, he said: The only reason the Japanese media painted him as a villain was Niigaki’s assertion that he could actually hear, and was therefore profiting off the disabled.

The real liar, said Samuragochi, was Niigaki. “It pains me,” he said. “I’d rather believe it’s not him saying these things, but that it’s someone else manipulating him.” Samuragochi blamed “the scurrilous Mr. Koyama” for orchestrating his downfall and for pressuring Niigaki to go along with it. He also suggested that Niigaki received generous compensation. “I understand he’s done very well off this incident,” he said. Niigaki is claiming full ownership of only two works, the “Sonatina” and the “Requiem.” But here Samuragochi sees yet another ploy, since these two pieces were explicitly composed for a disabled person and the victim of a natural disaster, respectively. “If I discard my co-authorship of those two, then I become this terrible man who exploits the suffering of others,” he said.

Samuragochi had a point. Public favor had shifted unanimously to Niigaki, even though Niigaki had helped create the lie. Niigaki had needed Samuragochi as much as Samuragochi needed Niigaki. Niigaki himself acknowledged this dependency, saying he was “grateful” to Samuragochi for the opportunities he provided. And Samuragochi had indeed contributed to the music, at least a little.

There was even evidence that he wanted to take their art in a new direction. At one point, he pulled out an essay he had written, titled “Rationality vs. Irrationality,” that was the basis for their still-unfinished Symphony No. 2. It described the music in detail, from the long, Cage-like silence at the beginning—a “conductor’s solo”—to the ratios of homophony and polyphony in different sections. He called this symphony the “antithesis” to Symphony No. 1, difficult where the latter had been easily grasped. The producers at Columbia thought it would be a tough sell, he said: “They wanted us to rework it to make it more like the successful ‘Hiroshima.’ We thought, Let’s finish it, but put it away until the times catch up.”

The irony is that Samuragochi didn’t have to lie. His story was compelling without embellishment. He was the child of Hiroshima survivors; he did have hearing problems; his brother did die young. If he and Niigaki had simply billed themselves as a team, they might have still shared fortune and fame. Instead, Samuragochi cultivated the image of a solitary genius. “I understood that people needed a story,” he told me. “There was this Beethoven idea, some larger-than-life figure, that I think the world wanted from me.” And it was that same need for a single figure—incarnated now in Niigaki—that brought him down.

When we spoke, Samuragochi could not resist overplaying his hand. He minimized Niigaki’s role to the point of insult. After I spent an hour trying to persuade him to reproduce something that he had composed, he paused dramatically, then broke out into song—an atonal moan of a melody, as if he were trying to sound as pathetic as possible. At another point, following a long discussion of his hearing, he lost his temper and yelled, “No!”—then asked innocently, “Was I shouting? I couldn’t hear.” He said he despised the Beethoven comparison: “The first time I heard that, I said, ‘Really? Isn’t this hyperbolic?’ ” But his former manager, Kurimura, said Samuragochi explicitly asked him to publicize the idea that he was a modern Beethoven.

I thought back to what Kurimura had said: He seemed to really think he was composing. It was like he had the temperament of an artist, but lacked the tools to actually create art. The closest he came to a masterpiece was the performance itself: the mass duping of a nation that exposed its own dreams and vulnerabilities.

I asked Samuragochi if he would ever compose again. “I think anything I released would be savaged,” he said. Then he thought for a minute. “This may be a sort of strange premise,” he began. “You could even call it a dangerous conception.” He was speaking slowly, pausing between each word. “Perhaps in some way there’s a benefit,” he said, “that this bizarre episode has brought some recognition to this kind of music.” His dream had been to express his love for Romantic music, and to make the world love it with him. At that, he had succeeded.

The lie, far from dooming their music to oblivion, may actually guarantee its survival. The sensational backstory has not deflated interest; it has become a selling point. When the Estonia National Symphony Orchestra announced that its final concert of the 2015 season will feature the “Hiroshima” symphony, the promotional materials described the Samuragochi saga with breathless, postmodern delight: Samuragochi “performed the role of a deaf genius wonderfully,” while Niigaki “was regarded as a national hero.” The lineup reads simply: Richard Strauss. Sergey Prokofiev. Mamoru Samuragochi/Takashi Niigaki.