Last week, Senators Rand Paul and Barbara Boxer unveiled a plan to give multinational corporations a massive tax break by allowing them to bring back overseas profits at a significantly reduced tax rate. This proposal—technically called "a repatriation tax holiday"—is what Paul Krugman would call a zombie idea. It never dies, no matter how many times economists explain its problems.

The U.S. corporate tax system currently imposes a 35 percent tax rate not just on domestic profits but also on foreign ones (with a credit for any taxes paid to foreign governments). But companies only have to pay those taxes when they repatriate the money—when they bring it back into the United States. In turn, U.S. multinational corporations have stashed nearly $2 trillion abroad in order to avoid paying taxes. This distorts company behavior in weird ways, such as when Apple chooses to take on more debt for stock buybacks instead of repatriating the money. It's cheaper for Apple to borrow money and pay interest on it than to repatriate their overseas profits and pay taxes on them.

Paul and Boxer’s solution to this problem is to give those companies the option to return the profits to the U.S. over the next five years and pay taxes on them at just a 6.5 percent rate, with a few strings attached. First, any company that uses a tax avoidance strategy known as an inversion—when a company merges with a foreign firm to change its tax jurisdiction and avoid U.S. taxes—in the next ten years would have to repay the tax incentive with interest. (I think that means they have to pay the full 35 percent rate on reptariated profits, plus interest, but the fact sheet doesn't explain exactly.) Second, they try to restrict the use of the repatriated funds towards areas that promote economic growth. “No funds may be spent on increases in executive compensation, or on increases in shareholder dividends or stock buybacks for three years after the program ends,” the summary of the plan says. Tax revenue generated from the plan would be earmarked for the Highway Trust Fund (HTF), which funds infrastructure and mass transit projects, and needs an infusion of cash by the end of May.

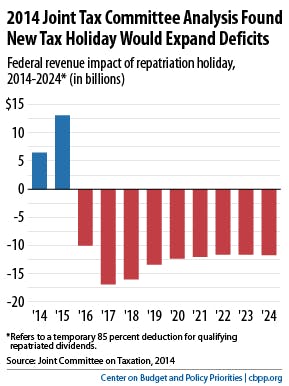

That may seem like a sensible policy that fixes two problems—profits stuck overseas and the funding shortfall in the HTF—at once. But it has two major flaws. First, while a repatriation tax holiday will provide a short-run boost to revenues, the academic evidence overwhelmingly finds that it will actually cost the government money in the long-run. That’s because a tax holiday gives multinational corporations an incentive to keep future profits abroad and wait for another tax holiday, reducing future revenues. Two independent studies found that that’s exactly what happened after the previous repatriation tax holiday in 2004.

On Monday, Senator Paul was interviewed on CNBC about the plan and took offense to the host’s suggestion that a repatriation holiday costs the government money in the long-run. “Your premise of your question is mistaken,” Paul said. “Most of the research doesn’t indicate that. In fact, there’s a prominent study by Robert Shapiro looking at the holiday in 2005 when we lowered the rate to 5 percent and his conclusion was that it brought about $300 billion of new capital home and brought in about $30 billion of new tax revenue.” When the anchor tried to challenge Paul on that point, he put one finger against his lips and shushed her. (Shushing starts at 3:10 mark.)

Shapiro’s study, which he co-authored with Aparna Mathur, has serious flaws. When it was first published in 2011, Chuck Marr, Brian Highsmith, and Chye-Ching Huang, all from the left-leaning Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, refuted the paper. “The study fails to account for the crucial fact that a repatriation holiday would encourage corporations to shift income and future investments overseas, at substantial cost to future corporate tax revenues,” they explained. In addition, they noted that Shapiro and Mathur use a “highly dubious assumption” by forecasting that post-tax holiday reparations would grow at the same average rate as they had between 1994 and 2003. Since corporations are expected to adjust their behavior based on the repatriation holiday, though, it’s very strange to forecast future behavior based on the behavior before the 2004 repatriation holiday. That would be like me giving you $1 million and then projecting your future consumption based on your consumption before I gave you that money. It entirely ignores that the fact that that $1 million will change your behavior.

Last year, the non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the repatriation tax holiday would cost the federal government $96 billion over eleven years. The Paul-Boxer plan is slightly different than the proposal that JCT examined, but it would still lose money.

The second problem with the Paul-Boxer proposal is its attempt to prevent companies from using the repatriated funds for dividends or stock buybacks. It’s a nice idea, but in practice it won’t work. Money is fungible. While pre-tax holiday, multinational corporations would have used domestic profits for operating expenses and investment, they will now use that money for dividend and share buybacks, and use the repatriated funds for operating costs and investment. The end result is the same as if the repatriated funds went to dividends and share buybacks: Shareholders get more money.

In addition, the proposal would only lead to increased investment if the multinational corporations that repatriated funds were actually cash-constrained. In other words, if they lacked capital in the U.S. to fund their investments. That seems unlikely as well. Those multinationals are all huge firms that have significant cash reserves and have spent lots of money in recent years on share buybacks. Money returned to shareholders would likely provide a small boost to the economy as shareholders buy other products and make other investments. But those benefits are likely to be indirect, small, and difficult to quantify.

When Paul said on CNBC, “I think this is probably the number one proposal that has a chance to be signed into law this year,” he may have been right—or, at least, it has the highest chance of making it to the president’s desk. That’s because it is a bipartisan bill that solves a crucial problem for Republicans: how to fill the shortfall in the Highway Trust Fund. Some moderate Republicans have suggested raising the gas tax, but there is no way that will actually garner enough GOP support to pass. Beyond that, Republicans haven’t offered many other ideas—and the May 31 deadline is quickly approaching.

With each passing day, the Paul-Boxer plan will look increasingly appealing, especially if many Democrats support it. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid is working with Boxer and Paul to make the legislation even more appealing to the left. Reid’s office didn’t return a request for comment but it would be troubling if Democratic leadership were helping to craft the bill.

Whether it will actually make it into law is another story. After the White House released its 2016 budget this week, their top economists repeatedly explained that they do not support a repatriation holiday. Instead, they suggest an overhaul of the corporate tax code that would impose a mandatory 14 percent tax on the $2 trillion overseas and impose a 19 percent tax on foreign profits in the future, regardless of whether they are repatriated. That would permanently eliminate any incentive for firms to stash profits overseas—a key difference between it and the Paul-Boxer plan.

President Barack Obama has not gone so far as to issue a veto threat to a repatriation holiday. Even if he does, it’s possible that Congress could have enough votes to override the veto. If there’s anything we’ve seen in this new Republican Congress, it’s that Big Business is their top legislative priority. But given the clear academic evidence against the Paul-Boxer proposal, hopefully they won’t get their way once again.