In May of last year, I took a trip to Nevada to report a profile of a political candidate. After a three-hour interview with my subject, a member of her communications team suggested we go to lunch. Midway through, I jumped up from the table and ran toward the restaurant’s bathroom. I was unable to make it all the way to the toilet and ended up retching on the floor of the stall. After cleaning up as best I could and shamefacedly informing the manager about the remaining mess, I was spent. I staggered out of the restaurant and found myself unable to do anything but take a quick nap (i.e., pass out) in the car of the campaign staffer.

I didn’t have food poisoning. I was six weeks pregnant, struggling with the biliousness and debilitating exhaustion that accompanies the first trimester for some women. I don’t recall this episode as cute, or with any of the maternal bravado sometimes found on parenting blogs. The staffer in whose car I crashed was really nice about it, but it was professionally humiliating. Pregnancy made it hard for me to do my job in the manner in which I’ve done it for the past 15 years. And there was no simple fix: I very much wanted to be pregnant; I also very much wanted to do my job well.

If you’re a person who has worked ambitiously, energetically, and efficiently for decades, it can be wildly discombobulating to find yourself suddenly tripped up by your own body, especially when it’s not illness or disability that’s stopping you, but among the most common and human of conditions. Yet this is a regular, lived reality for more women than ever before.

In 1970, the average woman had her first child at 21.4; by 2012, it was almost 26, an age by which many young adults are at least a few years deep into jobs or careers. Around 15 percent of first births are now to women over the age of 35, compared with just 1 percent back in 1970. Women across all classes are now participating in the labor market like never before, and far too few are able to spare a cent. Women comprise about 47 percent of the workforce in the United States and two-thirds of the low-wage workforce. In 2013, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, around 64 percent of mothers with children under six worked. In 40 percent of households with children, women are now the sole or primary breadwinners.

The confluence of all these factors means that women are now having babies smack in the middle of their peak earning periods and that their earnings are crucial to the economic stability of their families. And there is no denying that motherhood makes an economic and practical dent in the shape and solidity of their careers. University of Massachusetts sociologist Michelle Budig has found that, on average, an American woman’s earnings decrease by 4 percent for every child that she bears, a figure that sounds even more brutal when compared to the fact that after men have kids, their earnings increase, on average, by 6 percent. Researchers have also found that fathers are more likely to be hired and to be regarded as more competent employees than mothers.

These gendered discrepancies in post-childbirth careers can be understood via a host of historical assumptions about mothers and fathers; hoary ideas about providers versus nurturers, masculine responsibility versus feminine pliability. And, of course, there is the stratospheric cost of unsubsidized American childcare, a factor that leads many more women than men to drop out of the workforce or cut back on their professional commitments. These realities are abhorrent, but they are, at least, studied. What goes less noticed is the way pregnancy and immediate postpartum life itself plays a serious role in slowing professional momentum for women for whom the simple—and celebrated—act of having a baby turns out to be a stunningly precarious economic and professional choice.

The professional binds begin, in many cases, before conception. Women who are even thinking about trying to get pregnant often feel tethered to whatever job they’re in at the time. A move to a new job—a better-paying or more prestigious job, a job with more manageable hours or a more dynamic boss—can mean losing vested benefits like built-up sick days, vacation days, or family leave, and with them, any promise of being able to take time off after a baby. The Family and Medical Leave Act, currently the only federal leave protection available to American workers who have babies, does not require that an employer pay a new mother for a single day of leave; it merely protects her job for twelve weeks of unpaid leave, and then, only if she has worked at her company for at least a year. So, in many states, if you take a new job and then, two months later, discover that you’re pregnant, and nine months later give birth, your employer has no obligation to hold your job for you; he can simply decide that he’d prefer to avoid the hassle and expense of finding a temporary replacement and let you go. During childbearing years, changing jobs—even for a fundamentally better gig—can be a very bad idea.

Those prime childbearing years—mid-twenties to early forties—overlap precisely with prime professional years. This is when employees are most attractive to new employers, when they should be able to zip up ladders with the most alacrity. But for women who feel they might want to have a baby, hesitation can extend far longer than nine months: There’s no telling how long it will take to actually get pregnant. The professional paralysis brought on by anticipated pregnancy can drag for years—not because women are less ambitious, but because they are navigating the culturally and politically crafted disadvantages of our social policies.

And that’s to say nothing of the process of applying for a new job—or putting oneself forward for a promotion or a raise—while actually pregnant. Yes, there are official prohibitions related to discrimination in hiring based on gender or pregnancy. But imagine that your dream post opens up at another company or within your own; then imagine the likelihood that your pregnancy does not—on some level—serve as a strike against you. I have advised friends, and have been advised, that a woman is not required to tell a prospective employer that she is pregnant. But I’ve also done the math, considered the impact on a relationship with a new boss. I’ve always told; they always know.

These are the complicated negotiations many women in childbearing years must navigate with their co-workers and employers. What is happening to their bodies is a whole other story. You know what’s awkward at work? Vomiting. Also, trying to sit through a meeting or wait tables or complete your shift in a factory where physical conditions require vigilance, when suddenly you’re hit by a wave of fatigue so intense that it feels as if your bones may have melted. And it’s in those first few months of pregnancy, when everyone urges newly pregnant women not to breathe a word about their condition, for the (very legitimate) fear of miscarriage, that these symptoms are often most severe.

There’s another reason we don’t talk about the debilitations that pregnancy can involve: not every pregnant woman experiences them. And the assumption that pregnancy is going to hobble a professional woman can be nearly as bad as the lack of accommodation for the ways in which it might hobble her. The question of whether to acknowledge pregnancy as vulnerability—as a kind of temporary disability—returns us to age-old tussles between egalitarian and protectionist feminism.

I’m usually in the egalitarian camp: I don’t believe in treating femininity as a special diminished category. As appreciative as I am of all attempts to provide paid compensation to new parents, I find myself cringing at the use of “disability insurance” by some companies in some states as a means to patch together paid time off. Pregnancy does not—contrary to baby-oriented media eager to promote “Mommy brain”—make women stupid. It is not a physical handicap; expectant women are not rendered, by dint of their suddenly obvious femaleness, incapable of doing their jobs well.

Except when, sometimes, they are: for an afternoon or a day or a week or a period of months. When you are pregnant, there may be moments when you will not be able to stock the shelves or take the business trip, and there is too often no flexibility. In the pregnancy discrimination case argued in the Supreme Court in early December, former UPS worker Peggy Young asserted that her company would not allow her to modify her duties by lifting only light packages (as ordered by her doctor) during her pregnancy; she was placed on unpaid leave and lost her health care, pension, and disability benefits. Young’s co-workers who had been injured on the job were protected from this kind of treatment by the Americans with Disabilities Act. She was not.

This case is symptomatic of simple, systemic failures to account for the fact that a large percentage of the American workforce requires consideration of physical circumstance: circumstance which may or may not be enfeebling, which is very rarely long-term, and which—not for nothing—is central to the propagation of the species.

As you read this, I am home with a new baby, and paychecks are still arriving in my bank account. To say that I am lucky would be a great understatement. I have won the woman lottery.

Eighty-eight percent of American women do not get paid for a single day or a single hour after they give birth. When I had my first child, three-and-a-half years ago, for reasons related to my particular professional choices, I did not get paid leave.

This is what it felt like: It felt like I was a successful professional adult who, from the time I’d started scooping ice cream and busing tables in tenth grade, had always had a job, except for the times I’d been laid off. In this case, I hadn’t been laid off. I’d finally, at age 35, done the thing that everyone from Mitt Romney to most of Facebook had assured me was the most rewarding and most valuable—the most downright American—thing I could do: I’d had a baby. And my income—my economic independence—had vanished.

My plight was far cushier than most. I am partnered. My husband earns money (though the weeks he took off after the birth of our first child were also unpaid), the nature of my work permits flexibility and the ability to work from home, and I had a portion of a book advance. But that advance—meant to stretch over a year—was quickly lost to diapers and onesies and devices designed to suck snot from tiny human noses. I started writing journalism again—in a frenzied, desperate way—about six weeks after I had my daughter, but I was not really back in gear for three months and not earning anything like what I had been before the baby for a year—or maybe it was three years—after that. And again: compared with most new mothers whose income dries up as soon as they give birth, I was coasting.

For the majority of new parents, whose penniless postpartum months (or weeks, or days, or whatever they can afford to take without pay, which is often nothing) are simply the result of the way things are in a country that venerates motherhood but in practice accords it zero economic value, the situation is far more dire. It makes parenting a privileged pursuit, takes women out of the workforce, and ultimately affirms public and professional life as being built for men. Mercifully, the Obama administration is starting to come around to this reality. In January, the president announced that he would sign an executive order giving federal employees six weeks of paid family leave, and that he would pressure Congress to encourage better family and sick leave policies. The post that announced the shift was titled “Why We Think Paid Leave Is a Worker’s Right, Not a Privilege.”

When I discovered I was pregnant with my second child this spring, I was employed as a senior editor at the New Republic, but I had been there for less than a year, and, at first, on contract, not as a staffer. I was unsure of what was going to happen.

The New Republic is a venerable institution long dedicated to progressive politics. Back in the 1980s, two of its female editors, Dorothy Wickenden and Ann Hulbert, had babies. They asked then-editor and owner Marty Peretz for three months of paid leave and received it. But their claims were specific, personal; they did not result in comprehensive company policy. When my colleague—the editor of this piece—asked in 2013 about the New Republic’s maternity policy, she was initially told that there was none. She negotiated her way up to a promise of three weeks of paid leave and then—following intervention by colleagues, many of them young men—got boosted to eight weeks. New fathers were guaranteed three weeks of paid leave.

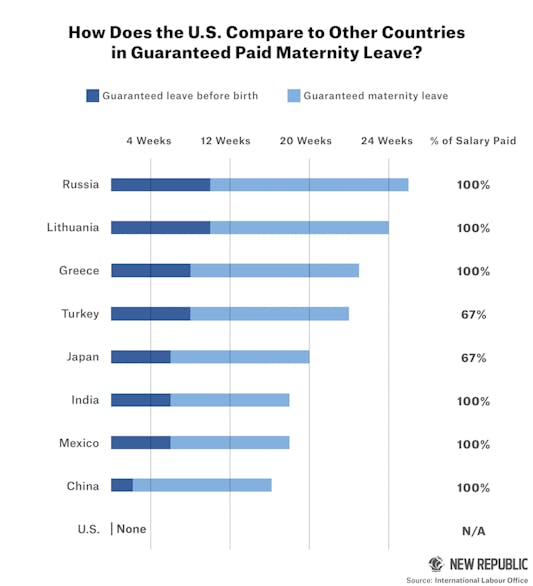

This policy, which my bosses graciously offered to me even though—since I had been at the company for less than a year—they didn’t have to, was generous by the standards of my industry, positively luxurious by the standards of this country. But it was meager in comparison to international practices, and, increasingly, in comparison to what is offered by high-end tech companies. In the past year, places like Google, Apple, Reddit, and Facebook have elicited mixed responses to their ample benefits packages, which include not just twelve weeks (and more, in some cases) of paid leave for mothers and fathers, but also baby bonuses, child care credits, subsidized fertility treatments, and egg-freezing.

These companies make many Americans feel anxious, for some very good reasons: Are their munificent incentives part of a plan to lure workers into becoming capitalist tech drones? Allowing them to have families but trapping workers on office treadmills that never allow them to spend time with them? Are they meant to enforce corporate loyalty to companies that profit by margins that will never be accessible to employees? Yes, maybe they are. What’s certainly true is that these benefits are accruing to a comparatively elite, educated workforce and not to those who could use them the most.

But it’s also true that these companies are capitalizing on a serious weakness in our social contract. The United States and its corporate structures were built with one kind of worker—frankly, with one kind of citizen—in mind. That citizen wage-earner was a white man. That this weakness is being addressed by employers faster than it is being addressed by Congress contributes to the widening of the class chasm. Policies that account for the fact that women now give birth and earn wages on which their families depend—and, for that matter, that men now earn wages and provide childcare on which their families depend—should not be crafted by individual bosses or corporations on a piecemeal basis that inevitably favors already privileged populations. They should be available to every American. But until we see a large-scale, national refashioning of family leave, the economic fates of childbearers will be left in the hands of the private entities that employ them.

In the weeks before I gave birth, the New Republic underwent some widely reported editorial turmoil. Its current owner, an online entrepreneur, hired a CEO from the tech world, who said some things that appeared to threaten the legacy of the magazine. The bosses who hired me and the majority of my beloved, brilliant colleagues—the very people who had helped my editor negotiate her 2013 leave—departed, leaving those of us who stayed bereft.

There were several reasons that I was not inclined to quit my job, but among them was the fact of my upcoming leave. Even had I wanted to, I couldn’t have quit. Despite the fact that I was staying on for a variety of reasons—because of an optimism about the future and less of an attachment to the New Republic’s past than some of my longer-serving colleagues—the easiest explanation of my actions turned on the fact of my late-stage pregnancy. My body and its condition defined my professional situation.

And then my new boss announced changes to the New Republic’s leave policy. Women and men at the company will now each receive 16 weeks paid leave after the birth or adoption of a new baby. These are lush—er, humane—Silicon Valley–style benefits, accompanying the Silicon Valley–style language that—reasonably— alarmed the New Republic’s former editorial team. This is the kind of policy that would allow a pregnant woman to take some time off before the baby is born, if she needed to.

I am immensely grateful for these benefits. Does my gratitude make me complicit in the decline of an American institution, or does it make me a lucky beneficiary of that institution’s progressive evolution? Do these expansive new benefits work as a carrot to draw new employees and then to keep them around? Is it such a bad thing to attract workers by offering them more equitable conditions, by considering that some number of them—male and female—might be producing children in the same years that they are producing content?

I don’t know the answers to any of these questions. And, in the end, I’m not sure I can afford to care. I’m a woman who’s just had a baby. My choices are limited.