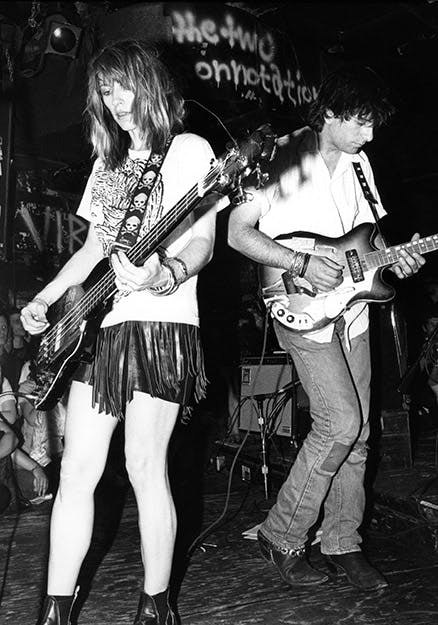

For years, women of my generation—the post-punk proto-hipsters who grew up in the cultural gap between second-wave feminism and the advent of the Internet—looked to Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon as proof that at least someone was getting it right. Really right. She retained her underground cred but wasn’t a starving artist. She had the drive of a New Yorker but the casual aloofness of a native Californian. She made visual art and started a clothing label, XGirl, on the side. On stage, she was surrounded by men—living the 1990s shoulder-padded dream of having it all, only in Converse and a miniskirt, with a bass guitar in lieu of a briefcase.

In Sonic Youth, Gordon was not just the band’s bassist but its “aesthetic (and business) conscience,” as Michael Azerrad puts it in Our Band Could Be Your Life, a history of punk and indie bands in the 1980s and early ’90s. It was Gordon who was tasked with delivering the news to their drummer that he was being fired, and later, when his replacement quit, she was the one to persuade him to come back. She provided creative gravitas, with her art-world connections, which eventually led to album covers by Gerhard Richter, Raymond Pettibon, and Richard Prince. “Within four years of existence, Sonic Youth emerged as an indie archetype, perhaps the indie archetype, the yardstick by which independence and hipness ... were measured,” Azerrad writes.

Like her contemporaries in the Riot Grrrl movement, Gordon was unapologetically feminist. She sang about the “fear of a female planet,” and wrote an entire song mocking Cosmopolitan’s advice to women. But whereas many Riot Grrrl bands and activists refused to talk to the media, Gordon was closer to the mainstream—appearing on MTV and making videos with Marc Jacobs at the same time that she was playing loud, discordant music and criticizing the co-opted girl-power message of the Spice Girls. Her influence throughout the industry was, and is, palpable: Gordon produced Hole’s first album, and recently appeared alongside Courtney Love in Yves Saint Laurent ads, where they were styled so similarly they looked like sisters. Several members of a younger generation of female musicians, like bassist Este Haim, cite her as a favorite. As Danish singer-songwriter MØ explained, “She had that attitude you could just feel.”

Part of her appeal was, undeniably, her partnership with Sonic Youth’s guitarist Thurston Moore, remarkable because it never attained the high-gloss finish of most celebrity relationships. Even when that veneer was partly shattered after her breakup from Moore (she found out he had been carrying on an affair with a woman 20 years his junior), she emerged somehow even cooler. The split was a form of validation: If it can happen to Kim Gordon, it can happen to any of us. “Thurston Moore Confirms He Is a Dick,” read one Jezebel headline. Her status was intact.

“Gordon was the ultimate hipster Renaissance woman I aspired to be,” wrote Lizzy Goodman in a 2013 Elle magazine spread that featured a photo of Gordon in gold heels and a black bodysuit—no pants—her trademark blond bob grown out slightly and covering one eye. At 61, she’s still gorgeous and stylish, but she has also not subjected herself to the obvious plastic surgery or fashion mood swings that have made other famous women her age seem dated. Or maybe she has, and she’s just better at making it look natural and effortless. Either way, she remained the ultracool girl next door.

“Anyone who writes an autobiography is either a twat or broke. I’m a bit of both,” wrote Slits guitarist Viv Albertine in her 2014 memoir. But there are many more reasons for musicians to pen their own accounts of their lives and careers: to help other people get sober (Anthony Kiedis); to cement their role as a rock elder-statesman (Carlos Santana, Mick Fleetwood); to indulge a lifelong tendency toward narcissism (Billy Idol, Mötley Crüe); to write themselves back into history (White Zombie’s lone female member, Sean Yseult); to sell more copies of a concurrently released album (Marilyn Manson); to set the record straight about bloodsucking industry suits (George Clinton) and long-held grudges (Galaxie 500’s Dean Wareham). If there is any structural similarity uniting the stories that emerge from these various imperatives, it is that they tend to open at a dramatic low point—an overdose, a motorcycle crash, a jail cell. Then it’s back to the beginning for a quick tour through childhood and an upward trajectory from there—a narrative arc that lends itself to the personal validation that so many of these books have as their ultimate exhortation.

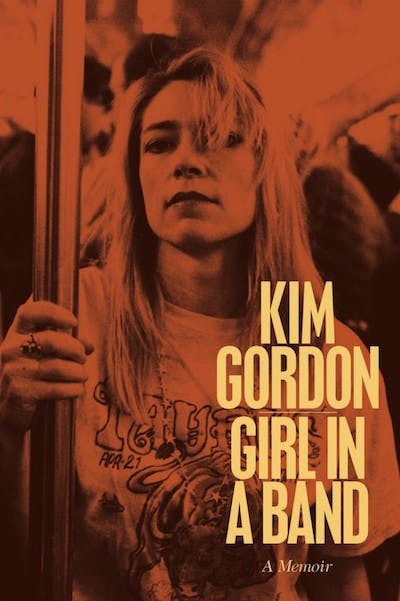

Now we can add Kim Gordon’s latest project to the list: Her memoir is titled Girl in a Band—a nod to her annoyance at being constantly asked what it was like to be the only female in her musical cohort. “I would not have chosen to do a memoir now, but people seemed interested,” Gordon recently told The Wall Street Journal. “Just because you write about the past doesn’t necessarily mean that you are looking back. I look at it as making something new.” It was a throwaway line, but it seems to imply a bigger and better scope than the traditional music memoir. That “something new” was an inviting proposition, particularly if you’re amid the demographic that idolized Gordon: a book that might be just as cool as Kim, a Just Kids for the generation that grew up in Patti Smith’s shadow.

Girl in a Band begins with the last gasp of the two defining relationships of Gordon’s life: the end of Sonic Youth and the end of her marriage in 2011. “That week,” she writes of the band’s final tour, “it was as if [Moore had] wound back time, erased our nearly thirty years together.” But it quickly slips into more comfortable territory, her upbringing in 1960s Southern California, where Gordon was raised, alongside a rebellious older brother who later developed schizophrenia, by an academic father and homemaker mother. “Even when I was a young kid pushing around clay objects at the UCLA Lab School, I knew I wanted to be an artist,” she writes. As a teenager she dated her classmate Danny Elfman, who would become known as a film composer and the lead singer of Oingo Boingo; after high school she worked for Larry Gagosian. After two years at Santa Monica College, she finished her degree at York University in Toronto, and then returned to Southern California where she enrolled in art school.

“When you study contemporary art in Los Angeles, New York is constantly touted as the only possible place to live,” she writes. And so, in 1979, at the age of 26, she drove East from L.A. with her friend, the artist Mike Kelley, and crashed at Cindy Sherman’s New York apartment. The city was “in crumbling shape,” she writes. She landed a part-time job at a gallery, wore “a hodgepodge of thrift-shop styles,” and hung out at downtown punk institutions like Veselka and CBGB. At night, she writes, Lower Manhattan “turned into a postapocalyptic hell, with rats, wrappers and cans interspersed every few feet with piles of stinking trash.” No Starbucks, no Pret A Mangers. Everything was covered with graffiti. “It was all incredibly stimulating.” She was given her first guitar by a woman she met at a party hosted by the artist Jenny Holzer and agreed to join an all-girl band that her friend was putting together. Soon after, one of the members of the short-lived band introduced her to Moore, who was five years her junior and in a band called The Coachmen.

Before long, they were living together and playing music. “As soon as Thurston came up with the name Sonic Youth,” she says, “we knew how we wanted the music to sound.” Because they didn’t have a drummer yet, Moore kept the beat by hitting his guitars with a drumstick. They played a handful of downtown gigs, recorded an EP, and released their first full-length album in 1982; by 1985 they were touring Europe. The band had been together for ten years when they signed with a major label. Geffen Records would be getting “a not-especially-commercial band with strong critical cred.” Sonic Youth would get to see “how more production money would affect our unconventional sound.” They released nine albums on the label.

Despite the extraordinary nature of her career, Gordon’s eventual struggles with reconciling her creative and personal impulses are pretty typical. “Sometime in my late thirties,” she writes, “I’d begun looking at babies. Babies on the sidewalk, in strollers, on shoulders. The problem was, I could never figure out the best time to start a family.” Gordon got pregnant anyway. Sonic Youth played the “Late Show with David Letterman” two weeks before she gave birth. “The machine never stopped, even though what I really wanted to do was lie down all the time.”

After her daughter Coco was born in 1994, the band traveled to Lollapalooza with a porta-crib in the tour bus and kept making albums and music videos—“dripping breast milk during a video shoot is not very rock,” she writes. Moore often stayed home with Coco when Gordon had other obligations, she acknowledges in a rare moment of tenderness, yet it wasn’t the parenting partnership of her dreams. “Like most new moms, I found that no matter how ... equal the man thinks parenting should be, it isn’t.” She adds, “This dynamic carried over to a lot of our relationship.”

In the late ’90s, Gordon and Moore decided to leave their apartment on Lafayette Street in order to spare their daughter the experience of growing up surrounded by “giraffe-packs of skinny models on every sidewalk within the Soho pedestrian mall of high-end consumerism.” They bought a big old house in Northampton, Massachusetts, but they both had trouble adjusting to small-town life—Moore in particular, writes Gordon. But she was feeling the pressure to be more conventional, too: “I’m a good cook and could fill the house with art supplies, but that was pretty much the extent of my homemaking,” she writes.

As Coco hit her teenage years, she grew wary of anyone who expressed interest in her famous parents. By that point, Gordon and Moore were more like quirky rock relics than vibrant figureheads, pulled out and dusted off for a guest appearance on a nostalgic episode of “Gossip Girl.” “You don’t know what it’s like to be your daughter,” Coco often said to her parents—a typical adolescent line that carries a different valence when your parents are indie-rock royalty.

If anything, Girl in a Band fits into the grudge-bearing category of music memoir. Although Gordon devotes pages to her opinions on art and music and includes fascinating descriptions of what it’s like to be onstage—“an intense, hyper-real dream, where you step off a cliff but don’t fall to your death”—her life as a girl in a band is ultimately inseparable from her life as a girl in a relationship, a very high-profile relationship that ended very badly. In the book, she’s doing a bit of intentional score-settling, sure. But she’s also still angry about everything that happened. And so the overall effect is not one of a serene, sober veteran looking back on her decades in the business or waxing poetic about a bygone era. Much of it reads like a journal entry, or worse, a banal Facebook rant about a long-term relationship crumbling: “Duhh, so I’m co-dependent.”

In her first post-breakup interviews, Gordon was frank but not overly confessional, obviously upset but not unnecessarily mean. “We seemed to have a normal relationship inside of a crazy world. ... And in fact, it ended in a kind of normal way—midlife crisis, starstruck woman,” Gordon told Elle. But in the book, her recounting of the breakup is pettier. She spends several paragraphs explaining how the other woman is “the user, the groupie, the nutcase.” She has a hard time explaining exactly what drew her and Moore together in the first place: “I wonder whether you can truly love, or be loved back, by someone who hides who they are.”

“Being a rock star,” muses Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash in his autobiography, “is the intersection of who you are and who you want to be.” Perhaps for women, rock stardom is more accurately the intersection of who you are and who you’re expected to be. And perhaps Gordon’s raw, messy tell-all is her way of rejecting our expectations. Rather than offer up claims that she’s just like everyone else, her book itself is proof that she’s not the unflappable rock goddess she’s made out to be. She is not a fashion icon, because “all I was trying to do was dumb down my middle-class look by messing with my hair.” She did not find the perfect balance between domesticity and creativity: “I wasn’t doing as much as I thought I should be doing individually—my art career was kind of on hold.” She is not a flawless advocate for all women in music because she thinks Lana Del Rey should “just off herself.” She has come to hate both the art world (which “has almost completely deteriorated into setting up a room with objects for sale”) and New York (“I wonder, What’s this place all about, really? The answer is consumption and moneymaking”).

It’s clear to me, after reading Girl in a Band, that women of my generation didn’t idolize Kim Gordon. We idolized the person we wanted her to be. The book is Gordon as she really is: still really cool, though more like a world-weary older friend than a living, breathing list of life goals. Girl in a Band is ultimately important as a corrective to our outsized expectations—for both Gordon and for ourselves. We’re all older now, too. And if our avid fandom has meant anything at all, we should be able to acknowledge that there’s no such thing as getting it right.