The American West faces its fifteenth year of low rainfall, sparse snowpack, and warming temperatures in what climatologists believe is only the beginning of a climate-change-induced megadrought that may last a century or more. Major cities across California recorded historically low precipitation levels in the last two years. At least 78 percent of the state is now categorized as suffering “extreme drought,” including the state’s Central Valley, the nation’s most productive agricultural region. California hasn’t been this dry in 1,200 years.

We tend to blame the exurban sprawl dweller for water waste. The profligate of the cul-de-sac, he obsesses over car washes, floods the Kentucky bluegrass on his lawn, tops off his swimming pool, takes the kids to water parks, and tees off at green golf courses tended among cacti. He is the wrong object of our ire, however. Personal and industrial consumption for drinking, washing, flushing, watering the lawn, detailing the car, and cooling nuclear plants, accounts for less than 10 percent of water use in the eleven arid states of the West.

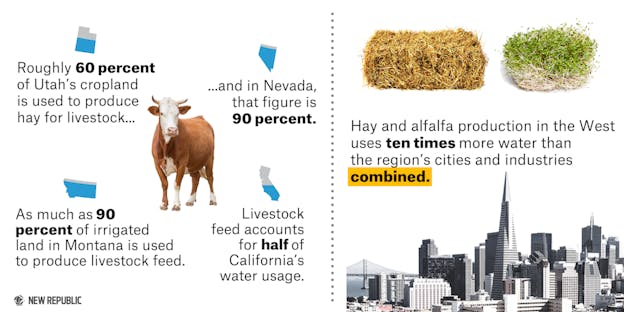

We’d do better to look at what we eat when casting about for villains of the water drama. Food production consumes more fresh water than any other activity in the United States. “Within agriculture in the West, the thirstiest commodity is the cow,” says George Wuerthner, an ecologist at the Foundation for Deep Ecology, who has studied the livestock industry. Humans drink about a gallon of water a day; cows, upwards of 23 gallons. The alfalfa, hay, and pasturage raised to feed livestock in California account for approximately half of the water used in the state, with alfalfa representing the highest-acreage crop. In parts of Montana, as much as 90 percent of irrigated land is operated solely for the production of livestock feed; 90 percent of Nevada’s cropland is dedicated to raising hay. Half of Idaho’s three million acres of irrigated farmland grows forage and feed exclusively for cattle, and livestock production represents 60 percent of the state’s water use. In Utah, cows are the top agricultural product, and three-fifths of the state’s cropland is planted with hay. All told, alfalfa and hay production in the West requires more than ten times the water used by the region’s cities and industries combined, according to some estimates. Researchers at Cornell University concluded that producing one kilogram of animal protein requires about 100 times more water than producing one kilogram of grain protein. It is a staggeringly inefficient food system.

One obvious and immediate solution to the western water crisis would be to curtail the waste of the livestock industry. The logical start to this process would be to target its least important sector: public lands ranching. The grazing of cattle and sheep on hundreds of millions of acres of federally managed land has been a fact of western rural life for over 100 years. It is considered an almost sacred profession. Yet its impact on the economy is actually quite small. According to University of Montana economist Thomas Power, public lands ranching produces just $1 out of every $2,500 in income and one out of every 2,000 jobs. Of concern to the steak lover: If this form of ranching ceased to exist tomorrow, the effect on the price and availability of beef would be negligible.

Grazing cattle and sheep in this arid landscape is the single most important cause of erosion and desertification on a public domain whose trees, rich soil, and grasslands function as ecosystem watersheds. “Livestock production, along with its coddled baby sibling, public lands ranching,” says Jon Marvel, founder of the Idaho nonprofit Western Watersheds Project (WWP), “is responsible for the largest single human use, degradation, and pollution of public watersheds in the western United States.” Stockmen cause over 95 percent of all western public land “dewatering”—when streams go bone dry—by diverting the natural flow to water cattle or grow hay. According to Marvel, a single cow on public land can deposit over a ton of waste on the ground every month, with a high percentage of that waste seeping into surface water. A single cattle feedlot in Idaho, located a mile from the Snake River, produces more untreated solid and liquid waste every day than four cities the size of Denver. “Every stream on public lands grazed by livestock is polluted and shows a huge surge in E. coli bacterial contamination during the grazing season,” says Marvel. “No wonder we can’t drink the water.”

Marvel, who retired from WWP last year, spent two decades haranguing and suing the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the government bodies that are supposed to regulate ranching on the public domain. “Forest Service and BLM staffers see their job as the protection and enabling of ranchers. They are the epitome of what is meant by agency capture.”

The influence of public land stockmen over government is an outlier in the annals of regulatory capture. Big Pharma, Big Defense, and Wall Street buy Congress with cash. But no wads of campaign contributions come from American stockmen. Yet, as Marvel puts it, “Western politicians always sit up and listen when they see a big cowboy hat and shiny belt buckle walk into their office.”

“It’s cultural capture,” says Debra Donahue, a professor of law at the University of Wyoming and author of The Western Range Revisited. “The ranching industry has captured the American imagination. And they have been given a special deal at great cost to the American public.”

The public lands livestock industry receives upwards of $500 million per year in state and federal subsidies for grazing fees, fence construction, road building and maintenance, forage improvement, and water diversions such as dams, pipelines, aqueducts, and stock ponds. Wildlife Services, a unit within the Department of Agriculture that implements hunting and trapping policies, slaughters hundreds of thousands of animals each year to aid stockmen: coyotes, wolves, beavers, prairie dogs, mountain lions, black bears, and other “pests.” Property tax on private ranch lands in Idaho is pegged at one-tenth the rate at which other lands are taxed. Ranchers receive below market-rate loans, and enjoy sales tax exemptions for the purchase of farm vehicles, tractors, andother equipment for raising hay. In 2013, the Obama administration directed the BLM to assess ecological damage caused by human activity in the western United States. Livestock was exempted from the study.

The cultural presence of cowboys in western state legislatures and Congressional delegations is ubiquitous. Local livestock associations act as political incubators, stacking the seats on county commissions, launching cattlemen into state legislatures, state and federal administrative positions, and into Congress. Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush won the presidency while carrying the cowboy flag: Both owned ranches and had a penchant for Stetsons.

Congress has been especially kind to public lands ranchers in the last year. Legislators attached a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act that exempted livestock permittees on public lands from review under the National Environmental Policy Act. Legislators further hamstrung federal land regulators by giving the secretaries of the interior and agriculture sole discretion to authorize environmental assessment of grazing permits. It also excluded the “trailing” of livestock from environmental review altogether, which effectively waived analysis of most domestic sheep operations.

Lawmakers from the western congressional caucus in the Republican-controlled House are now clamoring for new dam building and other water reclamation projects—at a time when the beneficiaries of irrigation in the West still owe $1.6 billion to the federal government for past efforts. “Dams and debt—it’s just another welfare subsidy,” says Marvel.

Everyone knows that climate-created drought in the West is made undeniably worse by livestock production. We are trying to bend the natural landscape to our will by raising a water-loving animal in the desert. The dewatering of streams and rivers for irrigation is the reason so many fish and amphibians in the West are endangered. The majority of dams that block the migration of salmon and steelhead are built primarily for irrigation water storage so we can grow alfalfa. “The capture of the West’s landscape by the cattle industry may be one of the biggest ongoing mistakes of our history,” says Wuerthner. And for what? To protect a mythological hero called the cowboy. Time to smash this idol of the American West and move on.