A study published in The Journal of Adolescent Health’s February issue poses a curious question: If the rate of pregnancy per 1,000 teen girls in the U.S. is 57, why is the rate of abortion only 15 per 1,000? Compared with other countries with complete official data, the number of abortions is strikingly low, and the number of pregnancies strikingly high: Out of 47 pregnancies in England and Wales, 20 will end in abortion; out of 25 pregnancies in France, 15 will. In fact, among countries with complete official data, the U.S. has the highest teen pregnancy rate and the second-to-lowest teen abortion rate. How to explain the discrepancy?

First, a few facts: The U.S. has one of the worst child poverty rates among developed nations, with one in three American children—including some teens—living in poverty, according to a recent UNICEF report. Worse, since the recession, child poverty in the United States has been on the rise. As alarming and shameful as American child poverty is, teen pregnancy has nonetheless been on the decline for decades, much thanks to the work of sex education programs and contraception campaigns. And yet, the gap between pregnancies and abortions among teens in the United States remains comparatively high. How come?

One possibility has to do with access; there is no doubt that other countries allow much readier access to abortion for teenagers than does the United States, and at much more affordable prices. But given that most women who have abortions in the states are young and poor, with some 40 percent living under the federal poverty line, a lack of access seems insufficient to explain the entire discrepancy. Therefore, the other explanation has to do with intent: What if American teens simply want to have children?

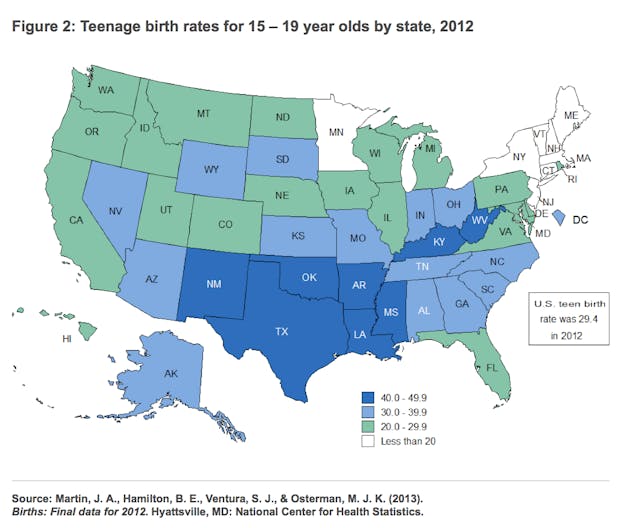

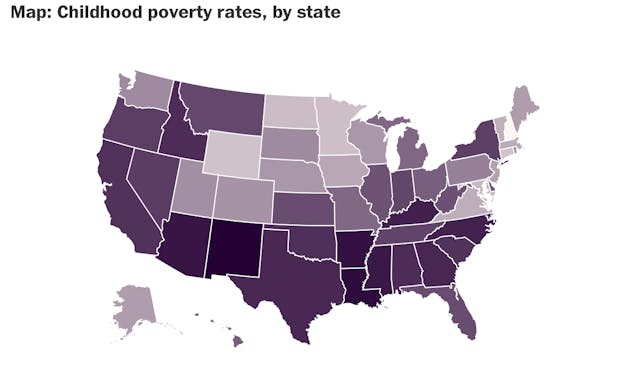

Among poor teenagers, there’s reason to believe this is the case. Consider these graphs, mapping teen births and child poverty respectively.

Teen births tend to be higher in states with higher levels of child poverty (shown in darker shades of purple) than in states with lower rates of child poverty. And for poor teens, this might make sense. A variety of studies have shown that having children can lower teenagers’ involvement in crime, drug use, and delinquency—meaning that, despite the dreadful outcomes associated with teen pregnancy in most policy literature dedicated to the subject, having kids can actually be positive and stabilizing for teen mothers. Further, researchers like Kathryn Edin, author of Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage, have argued that putting off pregnancy simply doesn’t make sense for women who find themselves without much hope of social mobility anyway. In those cases, Edin argues, motherhood provides a sense of stability, cohesion, and purpose. As Edin and Maria Kefalas argue in their article "Unmarried With Children," in the journal Contexts,

Until poor young women have more access to jobs that lead to financial independence—until there is reason to hope for the rewarding life pathways that their privileged peers pursue—the poor will continue to have children far sooner than most Americans think they should, while still deferring marriage.

In other words, to address teens who intentionally become pregnant and have children, the answer isn’t filling in knowledge gaps or providing contraception, since ignorance and equipment are not the determining factors in their decisions to become pregnant. For teens living in poverty, the solution must address the poverty itself, by way of providing feasible life alternatives that are genuinely within reach—a degree via free community college seems to be a fantastic start. Until then, it is likely that teen births and child poverty will continue to coincide, despite the best efforts of those wielding education and contraception against a problem ultimately economic in nature.