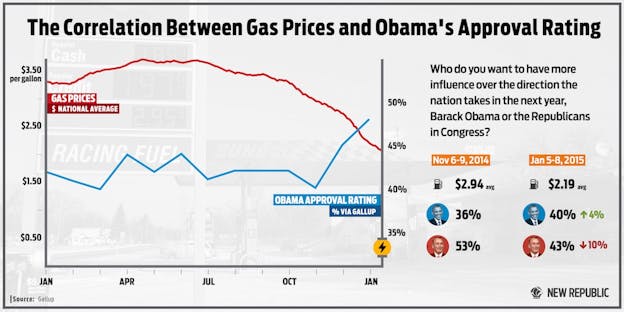

On November 4 of last year, the day of the midterm election, President Obama’s approval rating was near its nadir: 41 percent, with 53 percent of Gallup respondents saying they disapproved of the way he handled his job.

Two years earlier, by contrast, Obama was above water, 49-44. That election went a little better for him than the midterms.

Today, just two months after Democrats lost the Senate, Obama’s recovered more than half the ground he lost. His supporters like to attribute that to the resilience and defiance he has shown since the midterms—he announced executive actions to defer the deportation of millions of immigrants and normalize relations with Cuba, he has adopted a campaign-like mindset, and it stands to reason that if the blizzard of a late-stage presidential campaign could pull his approval into net positive territory, his recent actions might be responsible for getting him close to even. Perhaps if he’d been more of a presence on the campaign trail, Democrats wouldn’t have lost so badly.

But there’s another, better explanation, and it’s a crucial, real-time reminder that for all the effort that goes into running and understanding campaigns, political fortunes are exceptionally vulnerable to the vicissitudes of external forces.

The GOP’s huge November advantage on economic issues has collapsed. Broader economic improvement probably explains some of this (as might some of Obama’s burst of public-facing events since November). But the growing economy has yet to boost wages. Absent falling gas prices, the recovery would still feel pretty anemic to workers. Conceptually these are different issues, but at the end of the day they feel very similar. Cheaper gas puts more money in people’s pockets, just like a raise does—$2 billion a week, according to the Washington Post, or comparable to the fiscal cost of a 2 percent payroll tax cut.

Obama and Democrats don’t really deserve political credit for this, but that’s how politics works. Had prices fallen a few weeks earlier, or the election been held a few weeks later, Democrats would’ve probably had a much less unpleasant night. That’s a sobering reflection of the capricious nature of politics, especially if you, like me, spend a lot of time rooting your analysis in demographics, messaging quality, turnout strategy, and other heuristics.