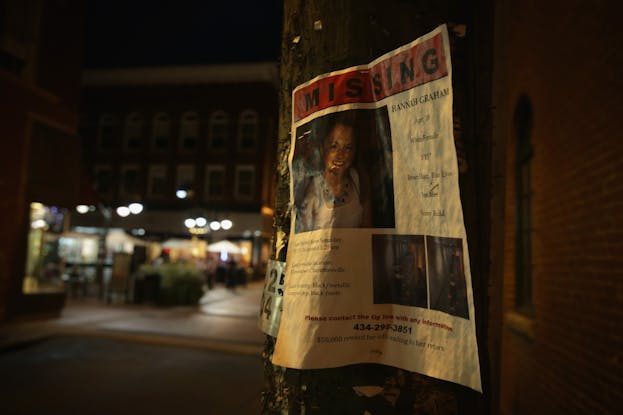

Hannah Graham disappeared in the early morning of Saturday, September 13, just weeks into the start of the fall semester at the University of Virginia, where she was a sophomore. She was last seen having a drink in a bar on the Downtown Mall, a wide brick pedestrian walkway flanked by sleek restaurants and expensive shopping in the heart of Charlottesville, over a mile from the UVA grounds.

Earlier that evening, Graham met some friends—many of whom were fellow members of UVA’s alpine ski team—for dinner at a small restaurant on campus. She attended several off-campus parties on a leafy street that stretches north toward one of Charlottesville’s busy arteries. She left alone. Video footage captured her in front of an Irish pub, then running across a dark bridge in the direction of the Downtown Mall. Cameras from Downtown Mall businesses then showed her walking alone just after 1 a.m. Around this time, she texted friends saying “I’m coming to a party…but I’m lost.” Footage also shows a white man following her, then a young black man approaching her and draping an arm over her shoulders. Later, Graham was spotted at a nearby bar with this second man, then leaving with him.

I teach creative writing and academic composition to undergraduates at the University of Virginia. I walk to get bagels underneath the bridge where Graham was seen breaking into a run. I go for drinks with friends at the bar where she was last spotted. So in the days following her disappearance, I developed new rituals. In the early minutes of consciousness, I began each morning by reaching for my phone and searching Graham’s name. The results were immediate and many. Since I’d last checked, just before going to sleep, there was always some development or some new voice to interpret the facts. My eyes scanned the articles I’d viewed hours before for any new meaning.

At first I was able to rationalize this intense interest in the information of Graham’s disappearance as motivated by the desire to inform myself so I might offer some wisdom to my students. But I noticed that I was now searching Graham’s name many times a day. A feeling of being unsettled took hold; something was misplaced or unorganized in my affairs, something poked, something bothered. I couldn’t quite settle into any task. I began to avoid the Downtown Mall altogether. I watched the police press conference on my iPhone while walking to a friend’s house for dinner, and though late already, sat outside their house to watch the end. Inside, when I talked about Graham, my voice rose and I got a sort of hot-faced feeling, as I do when I am embarrassed or shamed or am about to cry. From the cozy living room, people turned to look.

By Tuesday, The Albemarle Sheriff's Office, Virginia Emergency Operations, and the FBI were assisting the Charlottesville Police Department to search for Hannah Graham. Later, an aerial drone would be employed, the first time one has been used to search for a missing person in Virginia; the Graham disappearance would become the largest search effort ever to take place in the commonwealth. Talk around Charlottesville concerned little else. A bridge on campus was repainted purple, with the words “Bring Hannah Home.” More than a thousand students gathered in UVA’s stone amphitheater for a vigil. In class, my students were quiet, shifty. On the street outside, white news crew vans with large antennas parked illegally. The coverage was constant and, in the absence of finding Graham, thin: she had been a leader on her softball team, high school friends described her as “well-rounded.” Something began to smell in this coverage—it was hype.

Yet, when the University of Virginia and the Virginia State Police organized a volunteer search day for Hannah Graham on the Saturday following her disappearance, I went. At a required briefing the night before, I sat in John Paul Jones Arena, where Bruce Springsteen and Taylor Swift have performed, along with an estimated 1,100 others. Officials went over, in detail, what Graham was wearing the night she disappeared, black pants and a shiny crop top, prompting perhaps 20 minutes of follow up questions from the audience. “Did the crop top have sequins separately sown on or was it just a shiny material?” “How tight were the pants?” Over and over, Hannah Graham was described as “beautiful.” Over and over we were asked to help bring Hannah “home.” Over and over we were told to “stay hydrated” and “be safe,” as if I we were in a helicopter about to touch down in a combat zone. Over and over we were thanked for our “generosity” and told of our “impressive” turnout.

The next day, we were put into teams of volunteers and given orange vests. A city bus, repurposed for the circumstances, dropped us off at our search location, a residential area near the bridge where Hannah had been caught on videotape running. In my shiny orange vest, I felt purposeful. I pushed my hands into neat bushes surrounding doctor’s offices and peered into culverts. I felt tough and holy and good. A male UVA student was fastidious about opening every dumpster we saw, his face twisted into a look of sincere concentration. Once, overhearing a conversation speculating about Graham’s movements the night she disappeared, I was able to correct a factual error. I felt capable and sharp, like one of those tough lady detectives, Olivia Benson or Rhonda Boney. I am the only one who can see.

We didn’t find anything that afternoon. We sat in the shade of a tree, waiting for the bus to come and take us back to John Paul Jones Arena. “I lost my brother last year,” a middle-aged man in a camo hat who had driven from Richmond said, apropos of nothing. “So I know how it feels.”

In late May of 2005, eighteen-year-old Natalee Holloway of Birmingham, Alabama disappeared from Aruba while visiting the island on a senior trip. Holloway was white, pretty, and blond; the media coverage was immediate and intense. In contrast, when a 24-year-old pregnant Latina woman named Latoyia Figueroa disappeared from West Philadelphia mid-July of the same year, it took CNN nine days to pick up the story and The Philadelphia Inquirer even longer, and they did so only after local blogger Richard Blair wrote a outspoken critique pointing out the disparity and sent it to CNN. Figueroa was later found dead in a wooded area south of Philadelphia.

That year, a new term was coined by The Washington Post’s Eugene Robinson: “Missing White Woman Syndrome.” Roused by the Figueroa case, Washington University Professor Rebecca Wanzo wrote in Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, “Lost Girl Events rely upon an ideological framework in the United States that ignores the consistent and systemic neglect of some lost citizens, citizens who, if made into events, would challenge national discourses about who can represent the nation.”

According to Dori Maynard of the Robert C. Maynard Center for journalism education, the disappearance of “damsels” are covered much more vociferously than other victims because the majority of journalists are white and upper-middle class, and the aesthetics of damsels more easily allow them to recognize the missing girls as stand-ins for their wives and daughters. The more familiar the story is, the easier a narrative connection can be forged between victim and viewer. Indeed, NBC news conducted interviews during the search for Hannah Graham: “‘This could very well be my daughter,’ said volunteer Pam Graves, whose daughter, like Graham, is a second-year college student.” The Richmonder in camo: so I know how it feels.

This is not a revolutionary insight, but it might point to an important cognitive process that links identification, narrative, and action. In Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story, Roger Schank and Robert Abelson, Professors at Yale and Northwestern respectively, claim that the mind fundamentally operates by turning lived experience into narratives and subsequently most easily takes meaning from new stories that remind us of these stored narratives: “We are always looking for the closest possible matches. We are looking to say, in effect, well, something like that happened to me, too or, I had an idea about something like that myself. In order to do this, we must adopt a point of view that allows for us to see a situation or experience as an instance of ‘something like that.’” More recently, in his award-winning work of Psychology, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman theorizes that much of our mental life is governed by instinctive, subconscious processes that seek out “coherent” depictions of the world that reinforce our existing ideas of what stories mean and who we are in relation to others.

We have a sense-making organ in our heads, and we tend to see things that are emotionally coherent, and that are associatively coherent. … Coherence means that you’re going to adopt one interpretation in general. Ambiguity tends to be suppressed. This is part of the mechanism that you have here that ideas activate other ideas and the more coherent they are, the more likely they are to activate each other. Other things that don’t fit fall away by the wayside.

In other words, each of us, not only the media, construct narratives from strings of facts in ways that offer us meanings we already believe and desire.

If a reporter had asked me why I showed up for the Graham search day, I would have faltered. I had no ready answer. Perhaps I would have said: “I teach at UVA.” But there was something else. Unlike other pretty missing white girls like Natalee Holloway or Morgan Harrington, Graham seemed a little tomboyish and a little tough. In some pictures, she wears her hair slicked back or smushed under a baseball cap. Her eyebrows are a little over plucked, shaped like thin, kinked parentheses, as if she had never quite mastered cool feminine self-presentation or didn’t care to. She had parted ways with friends and was finding her own way home. The Roanoke Times reported she was “known for her wry sense of humor and spontaneous personality.” In other words, my mind immediately told me, she was an adventurous, independent, perhaps slightly eccentric white girl. I have been an independent, perhaps slightly eccentric young white girl, finding my own way home. This is not an altogether comfortable development.

This was not the first time someone had disappeared from the area in which I live. In the fall of 2012—my first semester in Charlottesville—Sage Smith, a 19-year-old transgender woman, went missing from Charlottesville; she was last seen at the Amtrak station. A poster bearing two photos of Smith—in one, Smith has short hair and wears a black suit, in the other Smith has long braids and a grey miniskirt—still hangs at the convenience store near my house. I spoke widely about the disappearance, triggering that hot-face-loud-voice effect. But when Smith’s family organized a vigil to pray for a safe return that December, I did not attend.

I suspect that the link between who we are supposed to care about and who we actually care about also plays out in a thousand tiny ways. Searching for Graham, I felt part of an efficient club, one of 1,100 in matching orange vests. Graham was a student at a large public university with exceptional resources and powers of information-dissemination; at a recent gynecological appointment my doctor told me not to walk alone and invoked Graham’s name. She disappeared in a state that historically privileges white, upper-class people and in a town that has profoundly marginalized its black citizens through centuries of relocation and subtle exclusion. These factors then—structural and cognitive—form an interconnected web of reasons, none of them simple, why the Hannah Graham case has risen to its current level of cultural salience and meaning.

On October 18, human remains which have since been identified as Graham’s body, were found in a dried-up creek bed a few miles outside of Charlottesville. Her case is now being treated as a murder investigation, and the main suspect is local man Jesse Leroy Matthews, the young black man shown putting his arm around Graham shortly before she disappeared. Matthews has been charged with “abduction with intent to defile” in the Graham case, as well as sexual assault, attempted murder, and attempted abduction in a 2005 unsolved case in Fairfax County, Virginia.

Matthews fled the commonwealth shortly after Graham went missing, and was later found camping on a beach in Galveston, Texas, before being extradited back to Virginia. Reports have also emerged that Matthews was a well-known personage on the Downtown Mall, known to touch female strangers in uninvited ways, and that he was dismissed from two Virginia universities on allegations of sexual assault.

We may read about these incidents and create a coherent narrative out of them. Many have already done so, calling Matthews a “monster,” a “creep,” and a “pedophile.” But these facts alone are not enough to tell the story. The language we use and how loudly we speak determines the value of the lives that are lost. I am proud I searched for Hannah Graham. Not because she was beautiful, not because she was smart, but because she was missing.

This post has been updated to reflect new information about Sage Smith's sexual identity.