Ruth Bader Ginsburg was considered a judge’s judge when she was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1993, an incrementalist who thought Roe v. Wade might have gone too far. Some liberals were wary. But they don’t worry about “R.B.G.” anymore. At 81, Ginsburg has become an icon to the left, inspiring fanwear and Tumblr tributes. Her dissents in the most hotly contested of the Court’s recent cases unabashedly defend progressive principles while taking her colleagues to task. (“The Court falters at each step of its analysis,” she wrote in her dissent of the five-four Hobby Lobby ruling.) Having avoided the spotlight for most of her two decades on the bench, she has emerged as an outspoken critic of the conservative majority, which she has lambasted in media outlets from National Law Journal to Elle. Now, however, liberals have a new fear: that Ginsburg has stuck around too long, and should have stepped down while President Barack Obama had the best chance of replacing her with a successor who shares her ideals.

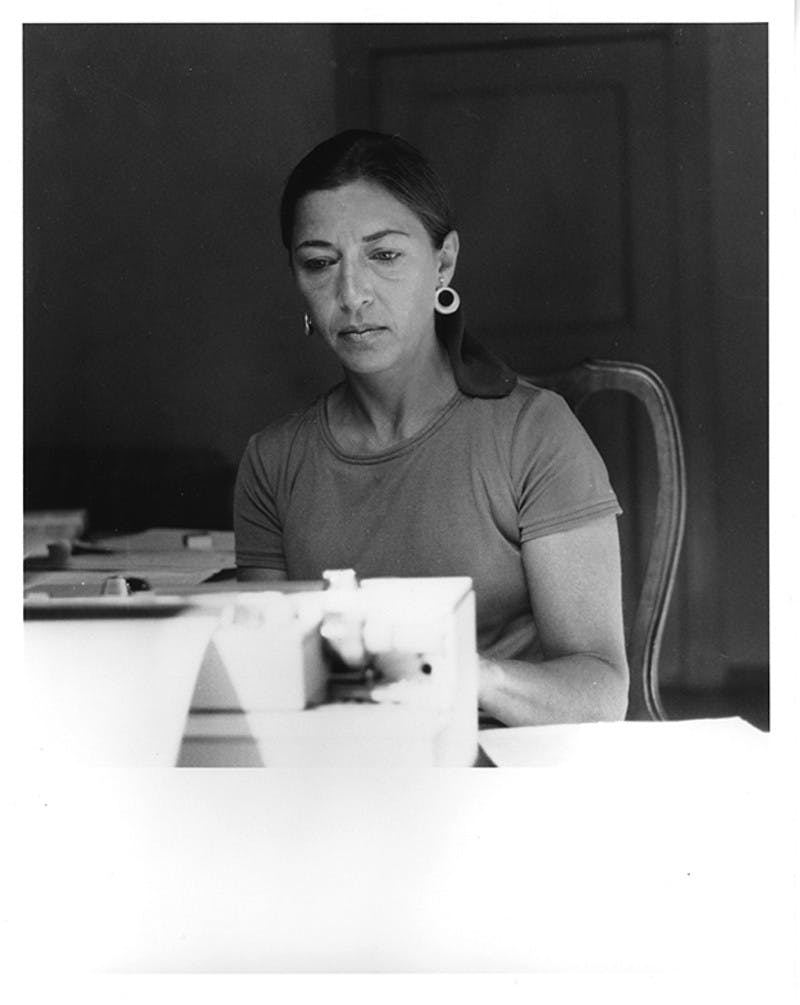

In mid-September, during a moment of quiet before the new term begins on October 6, I sat down for a conversation with Justice Ginsburg in the Supreme Court’s Lawyer’s Lounge. I have known Ginsburg since 1991, when we met while she was sitting on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and I was a law clerk for its chief judge, Abner Mikva. (One day, I ran into her in the courthouse elevator, as she was coming back from a workout in a leotard and leggings. She was a formidable presence, even in gym clothes.) We have kept in touch over the years. But this was our most extended discussion about the more outspoken approach she has adopted and where she sees the Court, and the country, headed.

JEFFREY ROSEN: You are famously a huge opera fan. But recently you’ve become an Internet sensation because of another kind of music. There are all these T-shirts going around the Internet saying, “NOTORIOUS R.B.G.” So my first question is: Do you even know who the Notorious B.I.G. is?

RUTH BADER GINSBURG: My law clerks told me. It’s not the first T-shirt. The first one appeared after Bush v. Gore. Those T-shirts showed my picture and, under it, the words “I DISSENT.” Now, there are many take-offs on the “NOTORIOUS R.B.G. shirt. Another T-shirt, done after the Shelby County decision, displays, “I LOVE R.B.G.”

JR: There’s also a “WHAT WOULD RUTH BADER GINSBURG DO?”

RBG: And another: “YOU CAN’T SPELL TRUTH WITHOUT RUTH.”

JR: How do you feel about having become an Internet sensation?

RBG: My grandchildren love it. At my advanced age—I’m now an octogenarian—I’m constantly amazed by the number of people who want to take my picture.

JR: When you were appointed, many people called you a minimalist. They said you were cautious. It’s only in recent years that you really found your voice and have become this liberal icon. What changed?

RBG: Jeff, I don’t think I changed. Perhaps I am a little less tentative than I was when I was a new justice. But what really changed was the composition of the Court. Think of 2006, when Justice O’Connor left us, and the cases since then in which the Court divided five to four and I was one of the four, but would have been among the five if Justice O’Connor had remained. So I don’t think that my jurisprudence has changed, but the issues coming before the Court are getting a different reception.

JR: What decisions would have come out differently if Justice O’Connor were still on the Court?

RBG: She would have been with us in Citizens United, in Shelby County, probably in Hobby Lobby, too.

JR: Do you think she regrets her decision to retire?

RBG: She made a decision long ago to retire at age seventy-five. She thought she and John1 would be able to do all the outdoorsy things they liked to do. When John’s Alzheimer’s disease made those plans impossible, she had already announced her retirement. I think she must be concerned about some of the Court’s rulings, those that veer away from opinions she wrote.

JR: Speaking of retirements, there are some who say that you should have stepped down before the midterm elections. How do those suggestions make you feel and what’s your response?

RBG: First, I should say, I am fantastically lucky that I am in a system without a compulsory retirement age. Most countries of the world have age sixty-five, seventy, seventy-five, and many of our states do as well. As long as I can do the job full steam, I will stay here. I think I will know when I’m no longer able to think as lucidly, to remember as well, to write as fast. I was number one last term in the speed with which opinions came down. My average from the day of argument to the day the decision was released was sixty days, ahead of the chief by some six days. So I don’t think I have reached the point where I can’t do the job as well.

I asked some people, particularly the academics who said I should have stepped down last year: “Who do you think the president could nominate and get through the current Senate that you would rather see on the Court than me?” No one has given me an answer to that question.

JR: Your health is good?

RBG: Yes, and I’m still working out twice a week with my trainer, the same trainer I now share with Justice [Elena] Kagan. I have done that since 1999.

JR: Do you work out together?

RBG: No, she’s a lot younger than I am, younger than my daughter. She does boxing, a great way to take out your frustrations.

JR: And what do you do?

RBG: I do a variety of weight-lifting, elliptical glider, stretching exercises, push-ups. And I do the Canadian Air Force exercises almost every day.

JR: What are the Canadian Air Force exercises?

RBG: They were published in a paperback book put out by the Canadian Air Force.2 When I was twenty-nine, that exercise guide was very popular. I was with Marty3 at a tax conference in Syracuse. We stopped to pick up a lawyer to attend the morning program with us. He said, “Just a moment, I have to finish my exercises.” I asked him what those exercises were. He replied they were the Canadian Air Force exercises and said he wouldn’t let a day go by without doing them.

The lawyer who told me about the Canadian Air Force exercises stopped doing them years ago. I still do the warm-up and stretching regime almost every day.

JR: Are those the exercises you did when I met you at the Court of Appeals in 1991?

RBG: No. I was part of Jazzercise class. It was an aerobics routine accompanied by loud music, sounding quite awful to me. Jazzercise was popular in the ’80s and ’90s.

JR: You were an admirer of Chief Justice Rehnquist. How have the workings of the Court changed under Chief Justice Roberts?

RBG: I was very fond of the old chief. I am also an admirer of the current chief, who had extraordinary skills as an advocate. He was a repeat player at oral argument, always super prepared, engaging in his presentation, and nimble in responding to the Court’s questions. As to the change, I regard the Roberts / Rehnquist change as a “like / kind exchange,” an expression tax lawyers use. Our current chief is a bit more flexible at oral argument: He won’t stop a lawyer or a justice in mid-sentence when the red light goes on. And at our conference, he’s a little more relaxed about allowing time for cross-table discussion. As to his decisions, there’s not a major shift. I’m hoping that as our current chief gets older, he may end up the way Rehnquist did when he wrote for the Court upholding the Family and Medical Leave Act. That’s a decision you wouldn’t have believed he would ever write when he joined the Court in the early ’70s. Chief Justice Rehnquist also decided that, as much as he disliked the Miranda decision, it had become police culture and he wasn’t going to overrule it. But the big change was not Roberts for Rehnquist, it was Justice O’Connor’s retirement.4

JR: This term there were more unanimous decisions than in any time since the 1930s. Why was that the case? Is Chief Justice Roberts achieving his vision of narrow, unanimous opinions?

RBG: We were unanimous, at least in the bottom-line judgment, in sixty percent of the term’s cases.5 That figure is deceptive because of the disagreement among people who joined the ultimate judgment. In some of the leading cases, those disagreements were marked. For example, the recess-appointment case. The Court was unanimous that Obama’s appointments to the NLRB [National Labor Relations Board] were invalid, but divided on the first two questions posed in that case: Does the president have the authority to exercise the recess power when Congress takes an intra-session recess or only when the recess occurs between sessions of Congress? The second question was, when must the vacancy occur? Must it occur during the recess? Or can the president fill up vacancies that existed before the recess? Those are questions of major importance and the Court divided sharply on the answers.

JR: And then of course there have still been some big five-four decisions. Most notably, Hobby Lobby, where you criticized your male colleagues for having a “blind spot” on women’s issues. Given Chief Roberts’s preference for unanimity, how have your dissents in those cases been received within the Court?

RBG: My answer to that would be, at least as well as Scalia’s attention-grabbing dissents.

JR: You’ve made it a priority as senior associate justice to have all of the dissenters speak in one voice. Why?

RBG: When I became the most senior member of four dissenters, I had a very good model to follow, Justice [John Paul] Stevens. He was always fair in assigning dissents: He kept most of them himself.

JR: [laughs]

RBG: I try to be fair, so no one ends up with all the dull cases while another has all the exciting cases. I do take, I suppose, more than a fair share of the dissenting opinions in the most-watched cases.

JR: And you’ve discouraged separate concurrences.

RBG: Yes.

JR: Why is that?

RBG: The experience I don’t want to see repeated occurred in Bush v. Gore. The Court divided five to four. There were four separate dissents, and that confused the press. In fact, some of the reporters announced that the decision was seven-two. There was no time to get together. That case was accepted by the Court on Saturday, briefed on Sunday, oral argument on Monday, decisions on Tuesday. If we had time, the four of us would have gotten together, and there might have been one dissent instead of filling far too many pages in the U.S. Reports6 with our separate dissents.

JR: Generally, you’ve been more reluctant to compromise than some of your colleagues. Is that a conscious decision?

RBG: That was so in Bush v. Gore. It was also true more recently in the Hobby Lobby case, where Justices Breyer and Kagan said we’d rather not take a position on a for-profit corporation’s free-exercise rights.

JR: So they wrote a separate dissent.

RBG: Just a few lines of explanation. We all agreed on what was most important. It didn’t matter whether the business was a sole proprietorship, a partnership, a corporation. The simple point is, we have the right to speak freely, to exercise religion freely, with this key limit. As Professor Chafee explained: “We have the right to swing our arm until it hits the other fellow’s nose.”7 I should emphasize that none of us questioned the genuineness of the Hobby Lobby owners’ belief. That was a given. But no one who is in business for profit can foist his or her beliefs on a workforce that includes many people who do not share those beliefs.

JR: What’s the worst ruling the current Court has produced?

RBG: If there was one decision I would overrule, it would be Citizens United. I think the notion that we have all the democracy that money can buy strays so far from what our democracy is supposed to be. So that’s number one on my list. Number two would be the part of the health care decision that concerns the commerce clause. Since 1937, the Court has allowed Congress a very free hand in enacting social and economic legislation.8 I thought that the attempt of the Court to intrude on Congress’s domain in that area had stopped by the end of the 1930s. Of course health care involves commerce. Perhaps number three would be Shelby County, involving essentially the destruction of the Voting Rights Act. That act had a voluminous legislative history. The bill extending the Voting Rights Act was passed overwhelmingly by both houses, Republicans and Democrats, everyone was on board. The Court’s interference with that decision of the political branches seemed to me out of order. The Court should have respected the legislative judgment. Legislators know much more about elections than the Court does. And the same was true of Citizens United. I think members of the legislature, people who have to run for office, know the connection between money and influence on what laws get passed.

JR: If a Republican wins the White House, could Roe v. Wade be overturned?

RBG: This Court had an opportunity to do that in the Casey case.9 There was a strong opinion speaking for Justice O’Connor, Justice Kennedy, and Justice Souter, saying Roe v. Wade has been the law of the land since 1973, we respect precedent, and Roe v. Wade should not be overruled. If the Court sticks to that position, there will be no overruling and it won’t matter whether it’s a Democratic president or a Republican president.

JR: And if Roe were overturned, how bad would the consequences be?

RBG: It would be bad for non-affluent women. If we imagine the worst-case scenario, with Roe v. Wade overruled, there would remain many states that would not go back to the way it once was. What that means is any woman who has the wherewithal to travel, to take a plane, to take a train to a state that provides access to abortion, that woman will never have a problem. It doesn’t matter what Congress or the state legislatures do, there will be other states that provide this facility, and women will have access to it if they can pay for it. Women who can’t pay are the only women who would be affected.

JR: So how can advocates make sure that poor women’s access to reproductive choice is protected? Can legislatures be trusted or is it necessary for courts to remain vigilant?

RBG: How could you trust legislatures in view of the restrictions states are imposing? Think of the Texas legislation that would put most clinics out of business. The courts can’t be trusted either. Think of the Carhart decision10 or going way back to the two decisions that denied Medicaid coverage for abortion. I don’t see this as a question of courts versus legislatures. In my view, both have been moving in the wrong direction. It will take people who care about poor women. The irony and tragedy is any woman of means can have a safe abortion somewhere in the United States. But women lacking the wherewithal to travel can’t. There is no big constituency out there concerned about access restrictions on poor women.

JR: How can that constituency be created?

RBG: For one thing, the advocacy of human-rights groups can make a big difference. Going back to the 1980s, I was speaking at Duke, not about abortion in particular, but about equal opportunities for women to be whatever their God-given talent allowed them to be, without artificial barriers placed in their way. During the question period, an African American man commented: “We know what you lily-white women are all about. You want to kill black babies.” That’s how some in the African American community regarded the choice movement. So I think it would be helpful if civil rights groups homed in on the impact of the absence of choice on African American women. That would be useful.

Ultimately, the people have to organize themselves. Think of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. The Court had said discrimination on the basis of pregnancy was not discrimination on the basis of sex, and a coalition was organized to get that law passed. The ACLU was the central player, but everyone was on board. The same thing happened after the Lilly Ledbetter case. It would take a similar kind of coalition. It must start with the people. Legislatures are not going to move without that kind of propulsion.

JR: When you think about your constitutional legacy, who’s your model?

RBG: I couldn’t identify one model. There are several. Certainly, the great Chief Justice John Marshall, who made the Court what it is today. You remember that John Jay, when he was elected governor of New York, thought that was a better job than chief justice. When George Washington wanted Jay to come back again, Jay said, no, the Court will never amount to much. Marshall made the Court an independent third branch of the government, so he is certainly a hero. Another justice, one who didn’t serve very long, six years, I think, was Justice Curtis, who wrote a fine dissent in the Dred Scott case.11 Some time later, the first Justice John Marshall Harlan, who dissented in Plessy v. Ferguson. Further along, of course, Brandeis and Holmes and their great dissents, mainly in the free-speech area but also in dissenting opinions explaining that social and economic legislation should be left largely to legislators and should not be second-guessed by the Court. And then, of course, Thurgood Marshall.

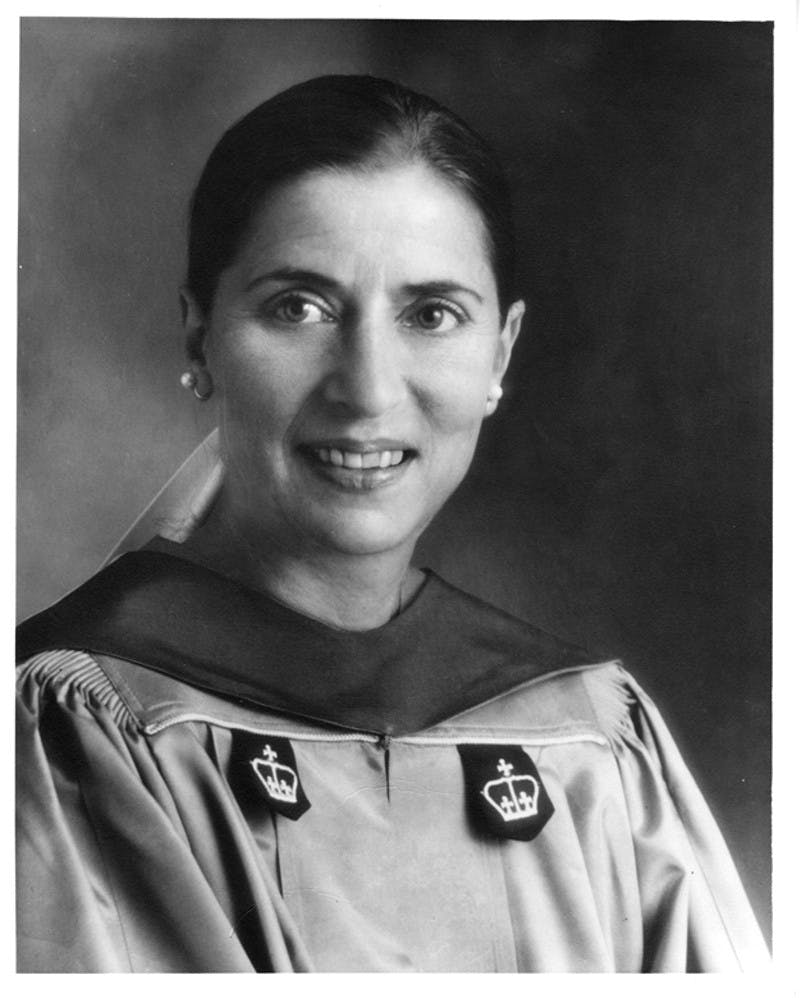

JR: When you were an ACLU litigator in the ’70s, you were called the Thurgood Marshall of the women’s movement.

RBG: He was my model as a lawyer. You mentioned that I took a step-by-step, incremental approach, well, that’s what he did. He didn’t come to the Court on day one and say, “End apartheid in America.” He started with law schools and universities,12 and until he had those building blocks, he didn’t ask the Court to end separate-but-equal. Of course, there was a huge difference between the litigation for gender equality in the ’70s and the civil rights struggles in the ’50s and ’60s. The difference between Thurgood Marshall and me, most notably, is that my life was never in danger. His was. He would go to a Southern town to defend people, some of them falsely accused, and he literally didn’t know whether he would be alive at the end of the day. I never faced that kind of problem.

JR: Let’s talk about the laws you were able to chip away at during your time at the ACLU. Can you walk me through some of the most important victories?

RBG: Every one of these cases involved a law based on the premise that men earned the family’s bread and women tend to the home and children. Wiesenfeld is probably the best illustration. The plaintiff, Stephen Wiesenfeld, was a man whose wife died in childbirth. He wanted to care personally for his infant, so he sought the child-in-care Social Security benefits that would enable him to do so. But those benefits were available only for widows, not widowers. Wiesenfeld’s wage-earning wife paid the same Social Security taxes that a man paid. But they netted less protection for her family. It made no sense from the point of view of the baby. The male spouse was disadvantaged as a parent. We were trying to get rid of all laws modeled on that stereotypical view of the world, that men earn the bread and women take care of the home and children.

JR: Have you kept in touch with the plaintiffs from those ACLU cases?

RBG: I’m regularly in touch with Stephen Wiesenfeld. I officiated at his son Jason’s wedding many years ago. Jason is now the father of three children. Stephen at last found the second love of his life, and I officiated at his marriage ceremony in May at the Court.

JR: How much did your experience with the ACLU influence the kind of justice you became?

RBG: When I was writing briefs13 for the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, I tried to write them so that a justice who agreed with me could write his opinion from the brief. I conceived of myself in large part as a teacher. There wasn’t a great understanding of gender discrimination. People knew that race discrimination was an odious thing, but there were many who thought that all the gender-based differentials in the law operated benignly in women’s favor. So my objective was to take the Court step by step to the realization, in Justice Brennan’s words, that the pedestal on which some thought women were standing all too often turned out to be a cage.

JR: And you’re taking a similar approach in your dissenting opinions today?

RBG: My dissenting opinions, like my briefs, are intended to persuade. And sometimes one must be forceful about saying how wrong the Court’s decision is.

JR: How has the dynamic on the Court changed as it has added more women?

RBG: Justice O’Connor and I were together for more than twelve years and in every one of those twelve years, sooner or later, at oral argument one lawyer or another would call me Justice O’Connor. They were accustomed to the idea that there was a woman on the Supreme Court and her name was Justice O’Connor. Sandra would often correct the attorney, she would say, “I’m Justice O’Connor, she’s Justice Ginsburg.” The worst times were the years I was alone. The image to the public entering the courtroom was eight men, of a certain size, and then this little woman sitting to the side. That was not a good image for the public to see.14 But now, with the three of us on the bench, I am no longer lonely and my newest colleagues are not shrinking violets. Not this term but the term before, Justice Sotomayor beat out Justice Scalia as the justice who asks the most questions during argument.15

JR: What’s your message to the new generation of feminists who really look to you as a role model?

RBG: Work for the things that you care about. I think of the ’70s, when many young women supported an Equal Rights Amendment. I was a proponent of the ERA. The women of my generation and my daughter’s generation, they were very active in moving along the social change that would result in equal citizenship stature for men and women. One thing that concerns me is that today’s young women don’t seem to care that we have a fundamental instrument of government that makes no express statement about the equal citizenship stature of men and women. They know there are no closed doors anymore, and they may take for granted the rights that they have.

JR: What is the opinion that you’ve written that you think has done the most to advance civil liberties?

RBG: Oh, Jeff, that’s like asking which of my four grandchildren I prefer. There have been so many. Well, in the women’s rights arena, the Virginia Military Institute case. So many people said to me, “Why would women want to go to that school?” I wouldn’t, and perhaps you, a man, wouldn’t either, but there are women who are ready, willing, and able to undergo that form of education, so why should they be held back by artificial barriers?

There was a decision on the civil side that didn’t get much press, it’s called M.L.B. v. S.L.J.16 The Court’s precedent was, if you are too poor to afford counsel or to afford a transcript in a felony case, the state must provide legal assistance for you. M.L.B. was a woman facing a deprivation of parental-rights proceedings. She was charged with being an unfit mother. She lost in the first instance and wanted to appeal, but the state’s rule was, to appeal, you must purchase a transcript. M.L.B. didn’t have funds to pay for one. It was technically a civil case, but I was able to persuade a majority of the Court that depriving a parent of parental status is as devastating as a criminal conviction. The Court decided that, if she can’t get an appeal without a transcript, then the state must provide the transcript at no cost to her. That was a departure from the rigid separation of criminal cases, on the one hand, with the right to counsel paid by the state and a transcript paid by the state, and civil cases, in which you do not have those rights. You must be able to pay. I thought M.L.B. was a significant case in that regard, getting the Court to think about the impact on a woman like M.L.B. of being declared a non-parent. It is devastating, much worse than six months in jail.

JR: And for dissents, your Gonzalez v. Carhart dissent is quite memorable.

RBG: That was in a partial-birth abortion case. And there what concerned me about the Court’s attitude, they were looking at the woman as not really an adult individual. The opinion said that the woman would live to regret her choice. That was not anything this Court should have thought or said. Adult women are able to make decisions about their own lives’ course no less than men are. So, yes, I thought in Carhart the Court was way out of line. It was a new form of “Big Brother must protect the woman against her own weakness and immature misjudgment.”

JR: Is there one case where you wish you had a do-over? A decision you regret or a position you wish you had articulated even more forcefully?

RBG: I would repeat the advice that Judge Edward Tamm gave me when I was a new judge on the D.C. Circuit. It goes like this: Work hard on each opinion, but once the case is decided, don’t look back; go on to the next case and give it your all. It’s not productive to worry about what’s out and released, over and done. That’s advice I now give to people new to the judging business.

JR: I know you have to get to another appointment. But before we wrap up, I wanted to make sure we talk about Scalia/Ginsburg, the opera. How did the show come about?

RBG: Derrick Wang, the writer, librettist, composer is a delightful young man. He was a music major at Harvard, he has a master’s in music from Yale, and then he decided he should know a little bit about the law. He’s from Baltimore and he enrolled in the University of Maryland Law School. And in his second year, he took constitutional law, and read opinions by Justice Scalia, opinions by me, sometimes for the Court, sometimes in dissent, and he thought he could make a very funny opera about our divergent views. So that’s how it all started. Many of the lines are straight out of opinions and speeches we’ve given. The piece opens with Nino’s rage aria, which begins: “The Justices are blind/how can they possibly spout this/the Constitution says absolutely nothing about this.”

There’s another scene where Nino is locked up in a dark room for excessive dissenting. I come to rescue him, entering through a glass ceiling and singing a “Queen of the Night”–type aria.

JR: I love the fact that your character first appears to the music of Carmen.

RBG: I like the last duet, “We Are Different, We Are One.” The idea is that there are two people who interpret the Constitution differently yet retain their fondness for each other, and much more than that, their reverence for the institution that employs them.

- Justice O’Connor’s husband, John Jay O’Connor III, who died in 2009.

- Called XBX in its female iteration, the program is a twelve-minute daily workout that includes a series of exercises like push-ups, running in place, and knee-raising. According to the original guide, “The XBX is designed to firm your muscles—it will not convert you into a muscled woman.”

- Justice Ginsburg’s husband, the tax law expert Martin D. Ginsburg, who died in 2010.

- O’Connor was replaced by Samuel Alito.

- The precise percentage of unanimous decisions last term was 66 percent, the highest since 1940. During the 2008 term, Roberts’s third as chief justice, the rate was just 33 percent, but it has climbed steadily since.

- The United States Reports are the bound volumes containing the Court’s final opinions.

- From “Freedom of Speech in War Time,” a 1919 Harvard Law Review article by the legal philosopher Zechariah Chafee Jr., who may or may not have actually coined the adage.

- That year, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the National Labor Relations Act in NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corp. The decision expanded Congress’s power to regulate the economy under the commerce clause.

- Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey was a 1992 case concerning a state law that imposed a 24-hour waiting period on abortions and required minors and married women to get consent from their parents or husband before undergoing the procedure.

- The 2006 case Gonzales v. Carhart upheld Congress’s ban on partial-birth abortions.

- “It is not true, in point of fact, that the Constitution was made exclusively by the white race,” wrote Curtis. “And that it was made exclusively for the white race is, in my opinion . . . an assumption . . . contradicted by its opening declaration that it was ordained and established by the people of the United States, for themselves and their posterity.”

- In the 1950 case Sweatt v. Painter, Marshall successfully argued that a black student, Heman Marion Sweatt, should be admitted to University of Texas Law School. That same year, in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, Marshall forced the integration of the University of Oklahoma’s graduate programs.

- Among Ginsburg’s most influential ACLU briefs was one written for Reed v. Reed (1971), in which her team convinced the Court that a man should have no automatic preference over a woman in the administration of a deceased child’s estate.

- Sotomayor’s average questions per argument was 21.6 to Scalia’s 20.5.

- The plaintiff’s and defendant’s initials, used in the case name to preserve their privacy.

This article has been updated.