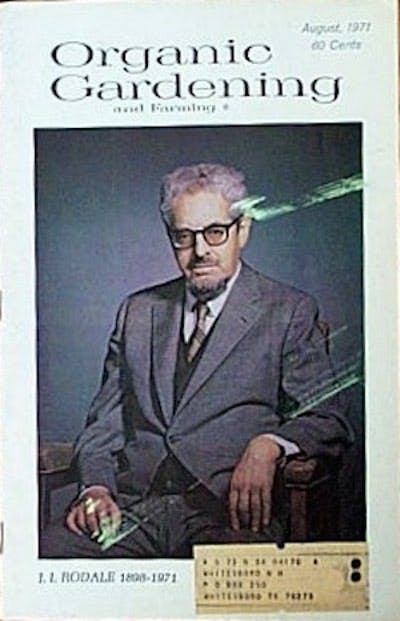

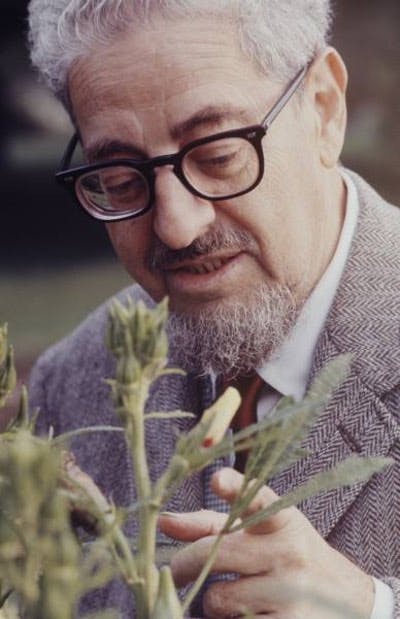

On June 7, 1971, Jerome Irving Rodale appeared on “The Dick Cavett Show.” The elder statesman of a growing organic food trend, he gushed about the health benefits of his diet, boasting that he “never felt better” and that he “decided to live to a hundred.” But after a commercial break, as Cavett interviewed his second guest, what sounded like a loud snore rose from Rodale’s end of the couch. The audience twittered, thinking that he was pulling a prank. But Cavett knew. When he looked over at Rodale’s bloodless pallor and gaping mouth his suspicion was confirmed—America’s most famous natural-health figure was dead of a heart attack at 72.

It was almost as if, having sought fame for decades, finally achieving it was too much for Rodale’s heart to bear. A first-generation American and son of a Lower East Side Jewish grocer, Rodale had always dreamed of making it big as an entertainer. In the 1930s, he self-published entertainment guidebooks—The Clown and The American Humorist—but they flopped. In the early 1960s, he authored or produced 30 health-themed plays, many of which were performed in his off-Broadway vanity project, the Rodale Theater. These, too, bombed commercially and critically, and Rodale angrily rebutted his critics in page-long ads he took out in the New York Times. To reviews of his play “Toinette,” Rodale bristled:

The critics had not reviewed “Toinette.” They had reviewed J.I. Rodale, editor of Prevention, the largest circulating popular health magazine in the world, a magazine that because it is telling the truth, it’s a menace to certain powerful medical and industrial interests. These people are building me up as a menace, a quack, a food faddist.

For over two decades, Rodale also dispensed nutritional and lifestyle advice in his monthly magazines, Organic Farming and Gardening (est. 1945) and Prevention (est. 1950). In their pages, Rodale summarily rejected postwar medical advances. “Isn’t there a better way of conquering polio than jabbing all the children in the country with a needle?” he wondered in a September 1955 Prevention article. And he made wacky, unfounded claims about what causes and cures various diseases. “Rimless glasses” and saltwater cause cancer, Rodale contended, whereas the earth’s “electricity … aids the body to combat cancer.” Foreshadowing the counterculture’s pastoral idealism, he wrote in an October 1955 Prevention editorial, “We must go back to nature, if we wish to live long. … We do not have to stop the advances of technology [but] we must not industrialize and technologize our own bodies.”

In his autobiography, Rodale boasted, “Twenty years before [Rachel Carson] and her Silent Spring appeared, I began lashing out continuously against the dangers to plants, animals, and people of these poisonous insecticides.” Even then, in 1965—three years after Carson’s book came out—Rodale’s audience was limited but devoted. It wasn’t until the late 1960s that American culture (or, more accurately, counterculture) caught up with his ideas and his magazines stopped running at a deficit. By 1971, Rodale’s circulation had skyrocketed, with slightly renamed Organic Gardening and Farming selling 720,000 copies and Prevention 1,000,000 in one year. The New York Times Magazine took notice, featuring Rodale in a June 6, 1971, cover story anointing him “The Guru of the Organic Food Cult”—and landing him, exactly one day later, on Dick Cavett’s couch.

By the time of his death, J.I. Rodale had become the organics authority in America. His significance to today’s food revolution cannot be underestimated—and not simply because Rodale Inc. is still churning out the above titles, plus Men’s Health, Runner’s World, and others. He was at the forefront of a critique of industrial agriculture that contained a wariness (if not downright paranoia) about government, science, and business’s role in food production. Had Rodale had his way, his alternative proposals would have earned him a place of influence and respect in mainstream American society. But since the USDA and others roundly rejected Rodale’s organic designs, he cast them and the modern foods system as villains in a Manichean morality play, with self-serving bureaucrats and businessmen plotting against earnest organic advocates. That narrative lives on today. When celebrities like Jenny McCarthy spread misinformation about the dangers of vaccines, or locavores like Michael Pollan preach relentlessly about the evils of large-scale food production, they’re following in Rodale’s reactionary footsteps.

Although the 1960s counterculture brought Rodale his national notoriety, he was more a nineteenth century health-food evangelist, in the mold of John Harvey Kellogg, than a hippie back-to-the-lander. In his autobiography, he describes himself as a “weak and sickly young man” who sought relief with vegetarianism, nudist camps, and other fixes. His maladies persisted until he moved his family and business to rural Emmaus, Pennsylvania, in the 1930s. There, he researched the farming methods of British agronomist Sir Albert Howard, whose compost-fertilized natural farming inspired Rodale to buy a farm and “raise as much of our family’s food by the organic method as possible.” The results were miraculous. Rodale enthused, “After about a year on the farm, eating food raised organically, we could see a definite improvement in the general health of the family.”

Rodale’s 1945 treatise on the miracle of compost-fertilized farming, Pay Dirt, made him, in his own words, “Mr. Organic.” That self-appointed title might have been meaningless had postwar America not been worried already about the toxic future ushered in by the atomic bomb. One of the profound changes prompted by the industrial-atomic age was a cultural condition that political scientist Robert Crawford describes as “somatic vulnerability.” Rodale explained this nervous social state in his autobiography: “The atom bomb has its atomic fallout. An ordinary heating system sends death dealing smoke into the atmosphere, as does the automobile. Foods are sold preserved with poisonous additives and food processors and government biochemists nod their heads in approval.”

In the early-mid 1950s, as public sentiment turned against nuclear weapons testing, a raft of studies linked the chemicals in ready-made foods to cancer. Calling pesticides “elixirs of death,” Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring accelerated distrust of agricultural industrialism. By the late 1960s, this cultural brew catapulted Jerome Irving Rodale onto the national stage as America’s organic seer.

In the early days, being “Mr. Organic” was rough. The publication of Pay Dirt, he wrote, “caused a stepping up of the campaign of abuse against us by magazines, newspapers, government and scholastic authorities.” The mainstream media lauded pesticides as modern miracles that made the “green revolution” of the 1940s-1960s possible; detractors were dismissed. In 1963, the New Jersey Department of Agriculture director wrote, “In any large scale pest control program we are immediately confronted with the objection of a vociferous, misinformed group of nature-balancing, organic-gardening, bird-loving, unreasonable citizenry that has not been convinced to the important place of agricultural chemicals in our economy.”

Rodale was used to having enemies. In his twenties, he suspected that anti-Semitism was stunting his career advancement, so he changed his name from Cohen to the more gentile-sounding Rodale. (In this instance, his suspicions may have been well-founded, but his response to later challenges to his organic crusade indicates a lifelong sense of embattlement.) In his publications and his personal research notes, he upbraided his foes. On food manufacturers, he exclaimed, “If a man is in a business making something that goes into people’s stomachs and a little chemical has to be used should he get out of the business? Or does he justify … that a little cannot do much harm TO MAKE A DOLLAR!” He also attacked doctors and their advocacy arm, the American Medical Association, saying they perpetuated the “greatest hoax in world history: the hoax that we must have disease … No wonder these jerks loused up the health situation. They confound problems and make problems where none exist.”

Rodale’s suspicion of doctors and drugs led him to embrace scientifically dubious alternatives, such as a dietary cure for polio. He claimed that the anti-polio course recommended in Dr. Benjamin Sandler’s pamphlet, “The Road to Polio Prevention”—featuring unprocessed vegetables and “protective foods like meat, fish, and poultry”—would halt polio because “really healthy children do not get polio.” After Dr. Sandler’s diet was broadcast in his local North Carolina newspapers, “polio cases dropped almost magically,” Rodale claimed.

Because the establishment wasn’t trustworthy, Rodale recommended an individualistic approach to health. “We must question every generally accepted health tenet or dogma,” he believed. “You must observe the effects on your own bodily processes of your basic daily actions. Make your own interpretation.” To this end, he served readers a smorgasbord of dire warnings and dietary endorsements. In My Own Technique for Eating for Health (1969), Rodale enumerated foods and vitamins needed for optimum well-being. Sunflower seeds, he claimed, “contain a living element, a germ which represents life.” Wheat, salt, and milk, on the other hand, caused everything from the halitosis to hardened arteries. For evidence, Rodale cited his own experiences or he cherry-picked data from various sources (some legitimate scientific studies, some specious). Often, reader testimony sufficed.

Occasionally Rodale’s notions were outright laughable—such as the theory that “plain club soda or seltzer water may be bad for your eyes,” or that “millions of heart attacks have been caused by susceptible people drinking artificially softened water.” Yet some of his still medically debatable advice has re-surfaced in today’s health food trends. Dr. William Davis, a gluten-free popularizer and author of New York Times bestseller (and Rodale publication) Wheat Belly (2011), would feel validated by Rodale’s November 1959 editorial exclamation, “I say don’t eat bread.” Sounding like Rodale incarnate, Dr. Davis warns on his blog, “The food you eat is making you sick and the agencies that are providing you with guidelines on what to eat are giving dangerous advice with devastating health consequences. You can change that today.”

While Rodale, like today’s health pontificators, considered food integral to happiness and longevity, contemporary organic advocates don’t share his curious views on race. In his inelegantly titled book, Happy People Rarely Get Cancer (1970), Rodale conjectured, “Negroes get less cancer than whites, for the Negro is a happy race. True, there is their problem of segregation, but the Negro race being what it is, I think a Negro sings just the same, and is not going to let segregation dampen his spirits as much as a similar problem would do to the white person.” Racial segregation, Rodale implied, gave African Americans protection from the drains of modern life—that, and their supposedly jocular disposition, explained their vitality.

Clearly Rodale was wrong about cancer and African Americans; he was wrong about the dietary cure for polio. Yet, his anti-modern, anti-establishment reflex reverberates through today’s alternative health and food movements. It does so in Jenny McCarthy’s stubborn anti-vaccine irrationalism, displayed most clearly in a 2009 Time interview where she said, “If you ask a parent of an autistic child if they want the measles or the autism, we will stand in line for the f___ing measles.” Or in the way that the food revolution’s spokespeople (Michael Pollan, Barbara Kingsolver, Alice Waters, etc.) advise concerned citizens to avoid mainstream food and eat their way to better health and a better world with organic, local victuals. Or in an email chain letter that I received recently —“Great information!! Cinnamon and Honey...! Drug companies won’t like this one getting around”—which claimed that this mixture can cure the flu, pimples, bladder infections, high cholesterol, and upset stomachs, and can prevent cancer and boost the immune system. It’s no different than Rodale’s claims about sunflower seeds or Brewer’s Yeast some 60 years ago.

It would be great if we could dodge illness and decay with one food or another, if organic kale smoothies prevented cancer. It would be great if we never had to depend on doctors or drug companies or science. But we all will become ill at some point, and we all will need medicine and scientists and hospitals to heal us. No amount of organic purism will prevent that inevitability. The clock can’t be turned back, either: globalization, modernity, and mass produced edibles are here to stay. Not all of us can dive into whole-food hedonism, as Michael Pollan describes in his New York Times Magazine article “The 36 Hour Dinner Party,” an account of his attempt to “roast, bake, simmer and grill” every meal over a wood-burning stove using tony local ingredients such as “one whole goat from the McCormack Ranch in Rio Vista, Calif.; …. and a couple of cases of wine from Kermit Lynch in Berkeley.”

Food reformers intimate that eating and cooking in this way is a test of personal will and political intelligence. When Alice Waters wonders, “How can most people so unthinkingly submit to the dehumanizing experience of lifeless fast food that’s everywhere in our lives?” she starkly sorts the masses out from discerning foodies. Educated shoppers swallow the organic costs for the foods’ obvious aesthetic and ecological superiority. The rest of us, controlled by what Pollan describes as “the corporate project of redefining what it meant to cook,” order take-out and buy “frozen peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches for [our] children’s lunch boxes.” If this food system is so pervasive and potent, how is it that Pollan and other food pundits can avoid its magnetism? Do they have special powers that the rest of us lack? For food revolution critic Julie Guthman, patronizing self-satisfaction “is the most pernicious aspect of the analysis by Pollan and others.” As she explains, “In describing his ability … to conceive, procure, prepare, and serve his version of the perfect meal, Pollan affirms himself as a supersubject while relegating others to objects of education, intervention, or just plain scorn.”

How organic/local believers’ careful consumerism presents a challenge to an agro-chemical giant like Monsanto, or a fast-food chain like McDonalds, is fuzzy at best. Despite its well-known flaws, the conventional food system extended the benefits of post-WWII nutritional prosperity to all Americans, even to the least well off who had suffered through decades of malnutrition and starvation. Rodale and his followers have correctly alerted us to this monolith’s environmental and health hazards. But does it have nothing of value to offer us?

Today’s alternative food movement must move beyond the food and health myths that confine it, and must bring as much critical rigor to organic utopianism as it does to agribusiness and factory-made foods. J.I. Rodale responded to modern existence’s unruliness with simplistic answers to complex questions and by retreating into self-health narcissism. It’s up to this generation to begin to envision reasonable solutions for everyone—not just those who can afford it, or who happen to live in Berkeley or Boulder—to eat and live healthfully in the twenty-first century.