OK, I admit it. I have a bad case of Sweden envy. You should have one, too—even if you are not a fellow working parent.

Raising a child and holding down a job is always hard. But in other developed countries, particularly those of Northern Europe and Western Europe, working parents have it much easier. The Swedes get up to 16 months of paid leave after the birth of a newborn, extra tax credits to defray the cost of child-rearing, plus access to regulated, subsidized day care facilities that stay open from 6:30 in the morning until 6:30 at night. The Danes and French benefit from similar arrangements. These programs are available to everybody, regardless of income, and the vast majority of working parents take advantage of them.

Here in the U.S., most of us can only dream of such programs. And it’s probably going to stay that way for a while. Local and state governments have introduced some initiatives of their own, but it’s taking a lot of time and confined to limited parts of the country. On Monday, the White House is co-hosting a meeting of academics, advocates, and business leaders to talk about work and family. (I happen to be moderating a panel there.) But while the president has proposed some ambitious initiatives, chief among them a universal pre-kindergarten program, nobody expects action on them anytime soon. Americans might like the idea of more family-friendly policies, but this Congress isn’t about to give it to them, particularly with the Republicans controlling one house. As Hillary Clinton conceded in a televised town hall last week, "I don’t think, politically, we could get it now."

The issue here isn’t just partisanship. The Europeans pay much higher taxes than we do—in Scandinavia, for example, the tax burden approaches or even exceeds 50 percent of national income. Governments across the ocean also have more control over business, particularly when it comes to the treatment of employees. This doesn’t seem to faze the European public. “We don’t mind paying high taxes as we and our children benefit,” one Stockholm parent told researchers a few years ago, expressing the prevailing sentiment. “We would not want to live a country where taxes may be lower but the benefits are less and you don’t get to spend time with your children when they are young.” You don’t hear such argument in the U.S. The prevailing assumptions (even among some liberals, I’m sure) is that the taxes and regulation to support such generous work-family policies would spoil the business environment and cripple the economy—creating a gentler society, perhaps, but also a less prosperous one.

It sounds like a classic case of soft hearts versus hard-nosed thinking. The data, however, tell a more complicated story. Policies that allow parents to spend more time with young children and get better day care have clear, quantifiable costs. They also have clear, quantifiable benefits—not just in the form of better child and maternal health, but also in the form of better retention and possibly higher productivity. As a matter of fact, there’s reason to think that America’s retrograde treatment of working families doesn’t help the economy at all. It might actually be hurting it.

How can that be? It’s straightforward to make that case with childcare, even though, of all the policies that fall under the “work-family” heading, it’s the most expensive. While estimates vary wildly, a European-style day care system would cost tens of billions of dollars a year, at the least. Even so, there’s plenty of reason to think the money would be a smart investment.

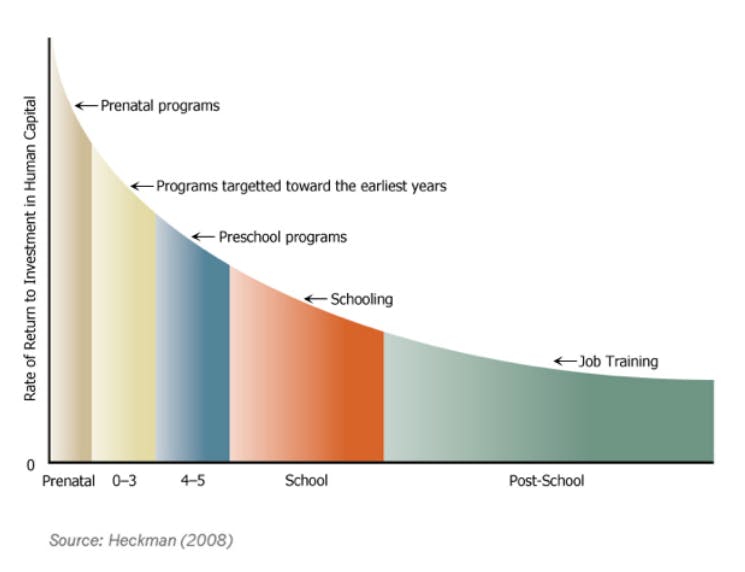

The most well-known advocate for this view is James Heckman, the Nobel winning economist at the University of Chicago. Heckman has developed a whole body of work around what he calls the “Heckman equation”—the idea that spending on education and training has its biggest impact early in life. The theory, rooted in well-established science of brain development, is that the first few years of life play a critical role in shaping future emotional, cognitive, and intellectual skills. Kids who get consistent, nurturing care are more likely to succeed in school, avoid trouble with the law, and have productive lives in the workforce.

Evaluations of high-quality early childhood programs in Chicago, suburban Detroit, and a bunch of other places have suggested the future gains (from a more productive workforce, less expenditures on jails, and so on) can outnumber the initial investment by as much as seven-to-one. Although it's hard to replicate those programs on a large scale, the magnitude of the gains suggest that, on net, a reasonably well-run early childhood program could actually make sense purely in dollars and cents.

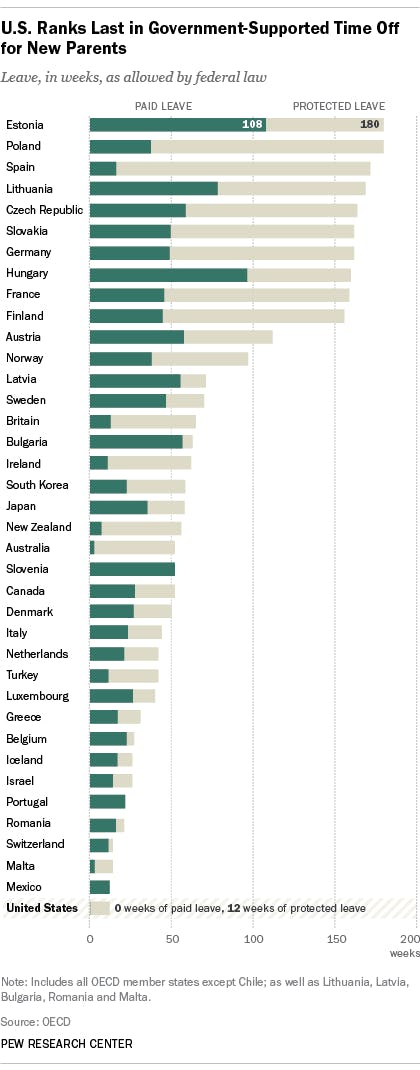

The case for more generous parental leave laws begins with the cost—and the fact it's one that most of the rest of world happily bears. Among developed nations, the U.S. is now the only one that doesn’t guarantee some kind of paid employee leave available for new parents. In these countries, firms don’t typically bear the costs directly. Instead, governments set up funds that work the way unemployment and disability insurance do—workers and employers pay into the funds, through some kind of payroll contribution, and then take money out of it when they become parents.

The money buys a lot—starting with better public health. “The evidence is pretty robust that extensions of paid leave for new parents leads to reductions in infant mortality,” says Jane Waldfogel, a Columbia University professor and one of the world’s leading experts on the subject. Exactly why this happens isn’t clear. One theory is that parents who stay home with newborns are more likely to make sure their kids get initial immunizations—and to put them to bed properly, on their backs, to avoid suffocation. Another theory is that women who stay at home with newborns are more likely to breastfeed. Whatever the cause, the effect is that babies end up healthier. There’s even some evidence that longer leave helps maternal mental health, although that research is a lot more fuzzy.

It's not the health effects of leave that stop the conversation from going forward. It's the economic effects—or perceptions thereof. Conservatives in particular complain that requiring paid leave would hurt businesses, because employers must scramble to fill vacant posts—and do so temporarily. But if you talk to actual business leaders, you hear a different, much more nuanced story. The trend among Fortune 500 companies has been towards offering longer leaves, with more compensation. Google, for instance, recently announced that it was extending paid leave for its employees by several weeks. One study found that the market even rewards such behavior; when companies announce they are extending parental leave, share prices rise.

The reason is that offering workers more leave tends to improve retention. Although the evidence is far from definitive, many studies have shown that, overall, new parents (and, in particular, new mothers) are more likely to return to work if they have the opportunity to take an extended leave for newborns. If companies don’t offer such long breaks—if they insist employees come back too soon—the new parents are more likely to abandon the job altogether and never come back.

When workers would rather work leave their jobs anyway, to take care of children, the companies aren’t the only ones who suffer. The economy does, too. And the impact may be more obvious now than it was before. The reason is that women, who still bear more responsibility for child-rearing in this country, also have more skills these days. Betsey Stevenson, a member of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, has been making this case loudly for the last few weeks. By making it more difficult for women with children to stay in the workforce, the U.S. is increasingly idling some of its most talented and productive workers—sometimes for a few years, sometimes forever.

Speaking at the Urban Institute a few weeks ago, Stevenson laid out the case:

Evidence from other countries and states that have adopted paid leave policies suggests that parental leave boosts female employment and helps increase subsequent earnings. At the same time, women who are offered maternity leave are more likely to return to the same firm, and many women who would not have otherwise returned to work re-enter the labor force within a year. Likewise, studies that have examined the effects of paid sick leave estimate these policies would increase businesses profitability, by improving productivity, and reducing turnover and absenteeism.

If the case for more family-friendly policies is really this strong, why does the government have to get in the middle of it? For one thing, corporations don’t always react quickly. The c-suite is still dominated by men, although that’s changing, and even when leaders seek to change policies the lieutenants don’t always follow.

Another problem is that low-income workers tend not to have access to these sorts of policies. While 72 percent of workers with a college degree have access to paid leave, for example, just 34 percent of workers with no education past high school do. It’s not hard to see why. If you’re a lawyer or engineer or physician, you can hold out for a company that helps with day care and offers generous leave, because companies desperately need your skills and will compete with one another to get them. But if you’re a hotel housekeeper or work as a security guard, you’re lucky if you can get a decent wage and health insurance. Without government to create rules and, in many cases, put up the money, benefits for working parents won’t be available to a large portion of the population — and it will be the portion that needs help the most.

That doesn’t mean creating these programs is easy—or without real drawbacks of their own. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio has his administration scrambling to set up a universal pre-K program, fulfilling a core campaign promise. He’s run into trouble, because there aren’t enough qualified teachers and caregivers in the city—and he won’t get them without more money.

A number of states have started paid leave programs. Typically they have created insurance funds that operate more or less the way unemployment insurance does—with employers and workers making small contributions into a fund that pays out to people who take maternity and paternity leave. But there’s the question of whether it should be universal (so everybody is eligible and gets the same payment levels) or means-tested (so that assistance phases out with income). The former is more popular—and more expensive. There’s also the question of how long to subsidize leave. When Germany pushed its paid leave past two years, female participation in the workforce actually started to drop.

That may or may not be a good thing. Once you start thinking about these policies seriously, you quickly confront some pretty complicated issues. To what extent should public policy encourage parents to stay home with children, at least when they are very young? Should gender equity be a goal and, if so, what constitutes equity? None of these questions are easy to answer. But right now we’re not even asking them questions, because we’re stuck on the idea that what they do in Denmark and Sweden and France would make no sense here. That’s totally backward. Working parents there have it much better than working parents here. We should be insanely jealous—enough to do something about it.