Lots of numbers are being lobbed about Monday after the Obama administration rolled out its climate-change plan. But to assess the move’s environmental impact, consider a single figure: 1 percent. That’s the rough proportion of yearly global greenhouse-gas emissions that the new EPA plan is projected to cut by 2030—if the plan survives a raft of inevitable challenges and is implemented in its proposed form.

That doesn’t mean partisans on the right are correct when they call the administration’s plan environmentally meaningless, and it doesn’t mean partisans on the left are wrong when they call it Obama’s biggest move on climate change so far. What it means is that nothing the United States does on its own will do much about climate change. For all the domestic fights the administration’s proposal will touch off, the move will have essentially no impact on global warming unless it prods other countries—the developing nations that will emit virtually all of the projected increase in global greenhouse-gas output in coming years—to radically clean up their acts. Will it do that? Doubtful.

U.S. carbon emissions were dropping long before today’s announcement. The administration’s new policy calls for the U.S. to cut greenhouse-gas emissions from the power sector 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. According to federal figures, emissions from U.S. power plants already fell 15 percent between 2005 and 2013. And though those emissions were expected to bounce back somewhat over the next decade and a half, the government was projecting even without the action announced today that they’d be 8 percent below 2005 levels in 2030. Why? U.S. electricity demand has basically flat lined, and power companies have been switching from coal to natural gas, which fracking has made cheaper and which burns about twice as cleanly as coal.

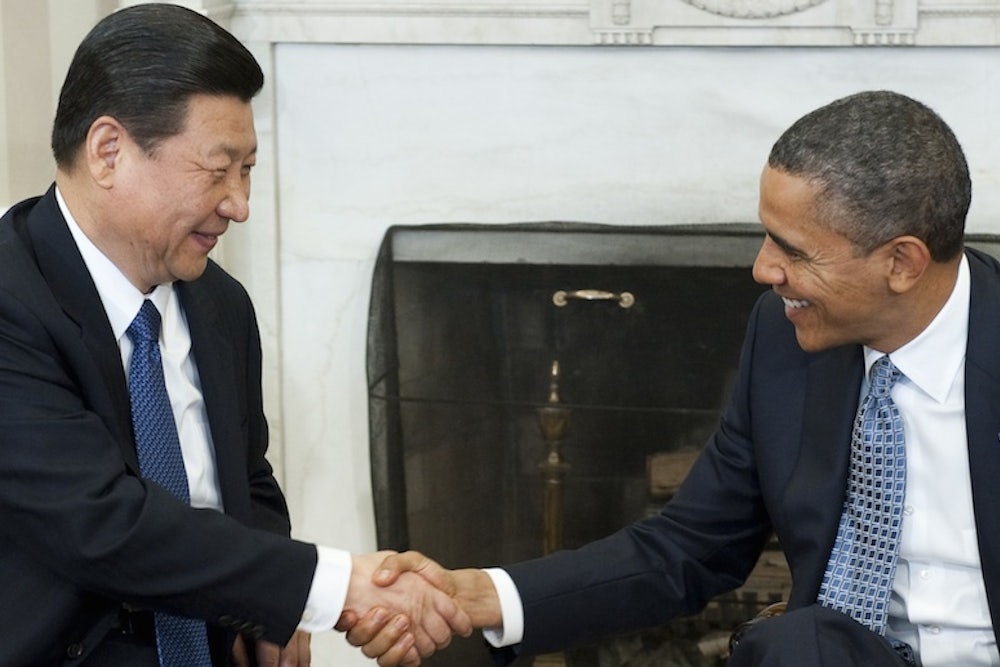

Yet carbon emissions have been soaring in the developing world—chiefly in China and India. That growth is expected to vastly outweigh the emission declines in the U.S. and other industrialized nations. History suggests the U.S. isn't likely to persuade other countries to do anything on climate change that those countries don’t already regard as in their national interests—and for reasons far more immediate than climate change.

To be sure, throughout years of international climate negotiations, diplomats from plenty of countries—China, India, Saudi Arabia, even the European Union—have cited America’s reluctance to curb its greenhouse-gas output as a big reason they aren’t doing more themselves. But that anti-American blame game is largely political rhetoric, intended to placate nationalistic constituencies back home. The notion often repeated by U.S. advocates of more-aggressive climate action—that a signal U.S. climate push would give the U.S. some decisive new moral authority that would persuade other countries to cry “mea culpa” and slash their own emissions in a paroxysm of concern for the glaciers—is wishful thinking, if past is prologue. Decisions about what to do on climate change are made chiefly on economic, not environmental, grounds. That’s because the environmental threat of global warming is tough to visualize and because capital investments in decarbonizing the energy system are likely to be so mind-bendingly large.

The real question about the impact of the administration’s new climate proposal is whether it will lead other countries to decide that curbing their carbon output is in their economic interest in a way that, before Monday’s announcement, they believed it wasn’t.

Markets are powerful motivators. Over the past decade, even as China surpassed the U.S. as the world’s largest greenhouse-gas emitter, it became the world’s largest producer of wind turbines and solar panels. But China hasn’t built up its renewable-energy industry chiefly because it wants to curb its carbon emissions. It has done so because it has targeted renewable energy as economically strategic: a sector it wants to dominate because it believes these technologies will grow into big global industries. Tellingly, China has ramped up these industries in the absence of any aggressive climate move by the U.S., though it has done so in large part to exploit a market spurred by climate policies in Europe. To the extent a new U.S. climate plan telegraphed to China and other developing countries that the U.S. is likely to buy or make more of these clean-energy wares, it could prompt them to ramp up those industries more.

Yet wind and solar power remain a tiny slice of global energy production. They’ve made no huge dent in global greenhouse-gas emissions so far. What would be more significant for the climate is if the Obama administration’s new policy led developing countries to change the way they use fossil fuels—coal, oil and natural gas—which will, according to most estimates, continue to provide the bulk of global energy for many decades to come.

China’s fleet of coal-fired power plants already is one of the world’s most efficient—meaning that, on average, it produces a lot of electricity for every bit of coal it burns, according to the International Energy Agency. That’s because China has been busy for years shutting down its oldest, dirtiest coal plants and replacing them with newer, cleaner versions. As with its wind and solar push, though, China hasn’t done this chiefly to curb climate change, and it has done it in the absence of any big U.S. climate policy. China’s main motive: To scrub its infamously brown skies, a serious public-health and thus domestic political threat. Those coal-fired power plants aren’t coughing out just carbon dioxide, an invisible, odorless gas. They’re also spewing the pollutants that cause smog and acid rain, which are all too easy to see and smell.

But Obama's climate plan could spur action in developing countries in at least two ways.

It could accelerate efforts to drive down the cost of the holy-grail technology known colloquially as “clean coal” and formally as “carbon capture and sequestration.” The idea is to make coal a climate-friendly fuel by capturing the carbon dioxide from coal-burning power plants and shooting it underground for storage instead of sending it into the air. So far, the technology remains a science project. But it’s conceivable the new U.S. climate push could spur more work on it—not just in the U.S, but also in the developing world.

Perhaps likelier, the climate plan could accelerate nearer-term shifts to lower-carbon energy in China and other coal-reliant exporting nations by raising fears there of a U.S. trade crackdown. There’s long been political talk in Washington that, if the U.S. slapped carbon constraints on its industry before China did, the U.S. might seek to compensate by hitting Chinese manufacturers with a carbon tariff on products they ship to the U.S. It’s not at all clear such a move has political legs; as an ongoing tariff war between the U.S. and China over solar panels shows, U.S. industry often divides over tariffs, because many U.S. firms depend on foreign companies as suppliers. But the protectionist chest-thumping in Washington has registered in Beijing. It’s partly why China has begun experimenting in a handful of provinces with trading so-called carbon credits, or permits to pollute. In their broad structure, those systems resemble the cap-and-trade carbon constraints that the administration’s new climate policy may spur in some U.S. states. If they expanded in China, they might prod more-efficient coal-fired power plants, the development of China’s prolific shale-gas resource, and redoubled efforts at energy efficiency.

One percent matters in milk and in American politics. It matters in global warming only if it catalyzes much bigger action on the other side of the globe. Advocates of a federal push to cut U.S. emissions have claimed it would prod developing countries to do even more. Now comes the test.