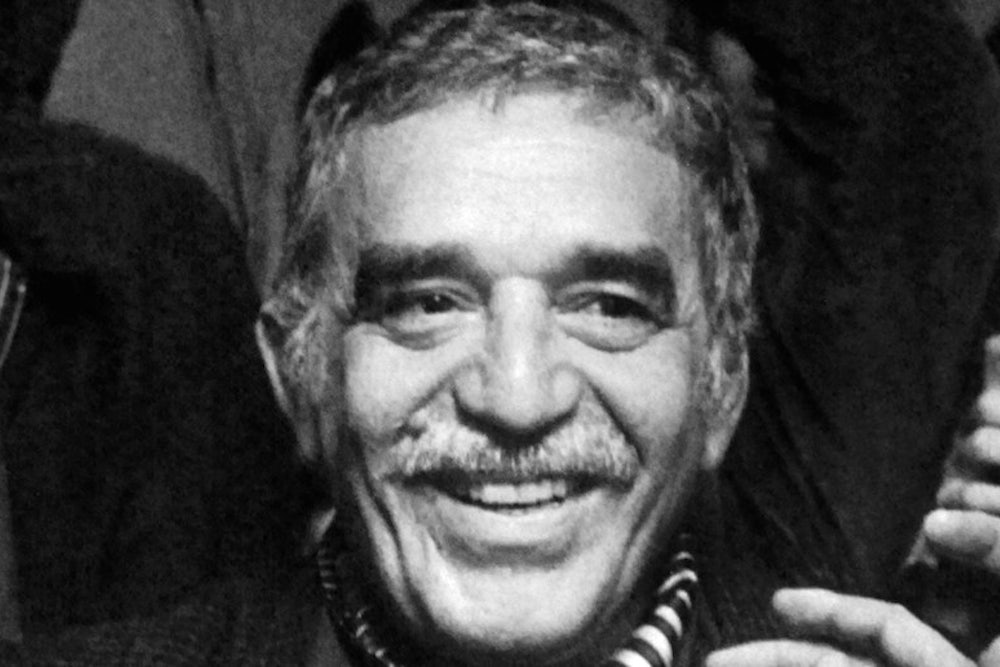

There is a lordly grandeur in Gabriel García Márquez's writing, and the grandeur animates every one of his books because, from beginning to end, he was gripped by an impossibly grand conundrum, which is the contradiction between lofty literature and lowly life. His characters uphold a glorious or even mythological concept of themselves, as if they were heroes of epic poems; and yet life insists on realities that are neither heroic nor mythological, until the characters end up battered and wounded. And, even so, they go on subscribing to their own version of events. They are noble losers, and the gap between nobility and loss is infinitely pitiable. In the greatest of his novels, The Autumn of the Patriarch (greatest in his own eyes, and in mine), you could almost weep even for the monstrous dictator, whose estimation of himself bears no relation to reality. In the greatest of his non-fiction books, News of a Kidnapping, about the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar and his kidnapping ring and its victims, you experience fear more than pity; and yet the gangsters and thugs likewise turn out to be immured in their own superstitions and crazy notion of themselves.

In the writings of García Márquez, even the sentences are suspended in a tension between literature and life. The insane sentences in Autumn of a Patriarch, which go on at preposterous length—the entire book consists of four paragraphs, as if indentation were something he abhorred—do report events, and, in that respect, are faithful to life and reality and to the ordinary conventions of communication. But the sentences are also lost in some mad theory of what a sentence is supposed to do, and you turn the pages looking for a period or a paragraph break and wondering “how much longer can this go on?” while the story, even so, continues to advance.

His famous landscape, in which strange and supernatural events keep taking place—a dictator is able to go on living for centuries—is sometimes regarded as a kind of primitivism or cult of folklore, which people enjoy. But the landscape is precisely where you see in its simplest form the same irremediable clash. The curious and supernatural phenomena are García Márquez's version of the marvels that, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the classic Spanish writers drew from the Latin poets and the Roman myths. Only, where the classic Spanish poets felt no great pressure to counter the world of marvels with the world of hard fact, García Márquez believes in both worlds at once, the supernatural and the natural, which means that literature is at war with life even in the landscape.

Five years ago, an English scholar named Gerald Martin published a grandscale biography from which I learned that, as a student, García Márquez studied the work of Rubén Darío, the Nicaraguan poet, and this seemed to me, when I first thought about it, the key to his literary enterprise; and now that I have thought a little more, I am convinced. It was Darío, the author of Cantos of Life and Hope and other poems, who posed the question that García Márquez went on to puzzle over in one book after another. Darío came from the middle of nowhere in late nineteenth-century Nicaragua and somehow received, at the hands of the Jesuits, a first-class literary education; and García Márquez came from the middle of nowhere in the Colombian "banana zone" and likewise received a first-class education. In both cases, education meant the Spanish classics, Luis de Góngora and the rest. And then, having received their educations, Darío in the 1880s and García Márquez in the 1950s were obliged to cope with the shocking discovery that modern life does not resemble the story of Galatea and Polyphemus as recounted by Góngora. Even so, Góngora was much too great to reject. And one cannot reject one's childhood. There had to be a way to square these two realities—the Spanish Baroque, which is literature, and the reality of modern life, which is not literature.

Darío tried to solve this problem by turning to Paul Verlaine and the Symbolist poets of France and borrowing a few verse techniques and exaggerating the cult of the irrational and the mad, all of which allowed him to continue writing poetry in the grand Spanish tradition, except with a difference. He went on believing in the ancient gods and myths, as per the Spanish Golden Age; and he excused himself for believing any such thing by acknowledging that he was out of his mind. One other innovation: Darío presented himself as nostalgic for the Golden Age of his own childhood, when he could believe with an untroubled conscience in the Golden Age of the Spanish poets. And he presented himself as infinitely sad because not even the Golden Age of childhood was Golden: "My youth—was mine a youth?" he asked in Cantos of Life and Hope. He gazed at ancient fountains and wept mystical tears. He also presented himself as partly Indian in origin, as if to insist that not everything that inspired him was Spanish and French and Latin, and something here was strictly Latin American and possibly still more ancient, unto the Aztecs. García Márquez figured out how to write novels on these same inspired themes. He acknowledged what he was doing, too. Somewhere in paragraph four of The Autumn of the Patriarch, with a fictional Darío having sailed into town on a banana boat, a sentence begins to say, "damn, how is it possible that this Indian can write something so beautiful with the same hand that he uses to clean his ass, that is to say, as exalted by the revelation of written beauty that was dragging the big feet of the captive elephant … " Oh, hell, how do you translate this kind of sentence?

We gringos tend not to notice the literary traditions that enter into García Márquez's novels, and that is because, in English and especially in American English, the weight of the literary past falls less heavily on the page. I do not know why that should be the case. Perhaps in English the connection to Latin and the ancient world, being more tenuous than in Spanish, is easier to ignore, which leads us to forget that any such connection could possibly matter. Or maybe the rhythms of English prosody are naturally freer than in Spanish, and the rules of verse and of prose have always been a little looser, which allows the modern English-language writers to press ahead without having to linger so mournfully over the poetic patterns of the past. Anyway, García Márquez was not an English-language writer. He was fixated from the start on the Latin American and Spanish literary past. And so, like his characters, and like his sentences, and like his landscapes, his appreciation of the literary tradition focused ever and again on the grand theme of literature and non-literature that he drew from Darío. He was a mono-thinker, which made him powerful.

His feeling for the Spanish and Latin American literary tradition, his love for it and his desire to rebel, lent one more strength to his novels, which we are bound to feel even if we have not the slightest inkling of what he is doing. He was trying to liberate the Spanish language and the whole of Hispanic culture from a tyranny of the past, even while continuing to appreciate it. His liberator's urge was not a matter of leftism, and absolutely it was not a matter of indignation over United States imperialism, although he was certainly indignant (and, in his part of Colombia, which had been dreadfully misused by the United Fruit company, he had reason for indignation). The urge was literary. Still, his effort to overcome the past, which is not political, feels like something political, as you read his books. You feel, in turning the pages, that he is proposing a liberation on so grand a scale that maybe the fate of a continent is at stake, and this is thrilling.

Some people have suggested that, like certain of the great nineteenth-century writers, García Márquez will end up being thought of as a children's author. Perhaps that will be the case. He is a Victor Hugo or a Mark Twain, and not a Stendhal or a Henry James—which I do not think of as a condemnation. In Latin America, younger writers long ago grew exasperated at "magical realism." Well, of course. Even so, he is an immortal. Yes, there is a lordly grandeur in his books.

Paul Berman is a senior editor at The New Republic.