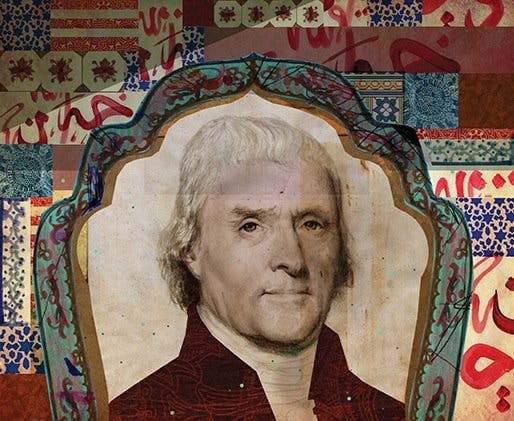

Thomas Jefferson's Qur'an: Islam and the Founders by Denise A. Spellberg (Knopf)

In the smear campaign before the election for the presidency of the United States, one candidate was accused by his opponents of being a closet Muslim. Some Christians “viewed all Muslims as agents of religious error and a foreign threat.” The United States faced a hostage crisis, as many Americans were taken hostage by Muslim powers and freed only after a ransom was paid. In one country alone, “more than one hundred Americans had been captured and imprisoned.” Accounts of these captivities, even forced conversions, were often bestselling books. Piracy off the coasts of North Africa was a major problem for American cargo ships. A “social Christian,” hoping to preserve “a purely Protestant Christian America,” was worried that aliens might take over the reins of power in the country and opined that “the few ... Jews, Mahomedans, Atheists or Deists among us” must, in the name of prudence and justice, be excluded “fromour publick offices.”

The time was not the 2000s but the 1790s, and the presidential candidate was Thomas Jefferson, who was, in Denise Spellberg’s words, “the first in the history of American politics to suffer the false charge of being a Muslim, an accusation considered the ultimate Protestant slur in the eighteenth century.” And it was not Captain Phillips who was taken hostage by Somali pirates. Much of Spellberg’s book is an account of those troubled times, and the remarkable efforts by a colorful cast of characters—many of the Founding Fathers, activists, clergymen, and politicians—to create a constitution that would, at least in theory, allow anyone who swore allegiance to it to become not just a citizen of the United States but even its president.

Their efforts were particularly remarkable “given the dominance and popularity” of many contemporary ideas, books, and plays that were critical of Islam. The Ottoman Turks, still a serious challenge to Europe, were invariably thought to be the only Muslims in the world, and the Ottoman sultan was often depicted next to the Catholic pope as the essence of heresy. And yet, in words borrowed from John Locke, one of the philosophical architects of liberal democracy, Jefferson insisted on a constitution wherein “neither pagan nor Mahamedan nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the Commonwealth because of his religion.” (It would take about a hundred and fifty years before the rights of full citizenship would be afforded to women and Jefferson’s words could be rephrased as “his or her” religion.)

For Jefferson, the idea of a Muslim president, or even a Muslim citizen, was an abstraction. He apparently did not know that there were many Muslims already in America: they were brought here as slaves from Africa. Many of them had been “seized and transported from West Africa,” Spellberg writes, and thus “the first American Muslims may have numbered in the tens of thousands.” (Glaringly absent from her narrative is a discussion of whether and to what extent the roots of the Nation of Islam, and Elijah Muhammad’s ideas, can be traced to these early Muslim arrivals. Peter Lamborn Wilson, in his book Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam, offers an interesting window into the early evolution of Islamic ideas among African Americans.) It would take African Americans even longer than women to have their full rights of citizenship recognized, but the greatness of the Founding Fathers lay precisely in crafting a constitution that would find its way to affording all Americans their full rights. Spellberg’s book is less about the Qur’an that Jefferson may or may not have fully read than it is a fascinating, sometimes meandering account of the Muslim odyssey in America—particularly in the first decades of the new republic. A brief afterword addresses some of the controversies about Islam in the post–September 11 era.

The book begins with a quote from Leviticus, inviting believers to treat “the stranger who resides with you ... as one of your citizens.” It goes on to offer a chilling account of the anti-Islamic polemics popular among Protestant reformers in Europe—and by extension, among the early settlers in America. Spellberg cites German Protestant woodcuts from the sixteenth century depicting “Luther’s vision of Antichrist as a beast with two heads—one a mitered pope and the other a turbaned Ottoman Sultan.” In Luther’s vision, “Muslim souls were already forfeit, condemned to hell for all eternity.” Ironically, long before Luther, Catholics themselves had often dismissed Islam “as the summit of all heresy.” Luther, along with many earlier Catholic theologians, dismissed Islam’s holy book as nothing more than a repetition of the Bible and a form of “blasphemy.”

In 1697, an Anglican clergyman named Humphrey Prideaux got into the game of bashing Islam by lumping Muslims together with deists. His book, The True Nature of Imposture Fully Display’d in the Life of the Mahomet: With A Discourse Annex’d for the Vindicating of Christianity from this Charge, Offered to the Consideration of the Deists of the Present Age, attacked Muslims and deists for rejecting the divinity of Jesus and “believ[ing] in a unitary God.” Despite his vitriol, Prideaux was right on one point: Islam certainly does not accept the idea of a Trinity, or of a divine Jesus; the Qur’an clearly declares that the idea that Christ was the son of God is a lie. Protestants, according to Spellberg, commonly believed that “Islam and Catholicism were both violent faiths, spread by the sword.”

Such theological anti-Islamic tracts, available in Europe and reprinted in America, were part and parcel of centuries of Christian polemics against Islam. In this disputation, incidentally, Islamic theologians were generally handicapped by the fact that Jesus (and Moses) are repeatedly and reverentially mentioned in the Qur’an, and Mary has a whole chapter of Islam’s holy book named after her. Thus Moses, Jesus, and Mary could not be subjected to nasty attacks similar to those hurled at Islam and the prophet Mohammed. But these Christian anti-Islamic polemics were not the only texts popular in America at the time. It is surprising to learn that “the first play about Islam performed in America was written by François-Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire.” Long before “cultivating his garden,” Voltaire had written a blistering attack on Islam and the Prophet called Le Fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophète. Initially staged in Paris in 1742, the play was revived in London in 1776 and became a hit, and in 1780 the play would be performed in America.

Into the whirlwind of these attacks came the likes of John Locke, who began to demand not just tolerance toward Muslims but also equal rights, and George Sale, whose earnest translation of the Qur’an differed from earlier versions that were invariably bent on attacking Islam. Jefferson placed Locke among his “trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced,” along with Isaac Newton and Francis Bacon. Sale, the translator of the Qur’an, was not one of the Jeffersonian trinity, but a copy of his third edition, printed in 1744, was in Jefferson’s library. Spellberg makes clear that “the phrase ‘Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an’ ” does not imply that references to the book were “numerous, detailed, or systematic” in his writings, or that he seriously engaged with the text. “Suffice it to say, Jefferson did subscribe to the anti-Islamic views of most of his contemporaries, and in politics he made effective use of the rhetoric they inspired.” Yet when it came to the question of rights of citizenship, Jefferson “agreed with Locke that toleration should be denied those ‘who will not own and teach the duty of tolerating all men in matters of religion.’ ” He stood firm in the belief that “the right to one’s chosen faith” was a “natural endowment, not contingent on even the most beneficent God.”

The genius of democracy is that, while some forces were busy spewing anti-Islamic rhetoric, enlightened Westerners such as Henry Stubbe wrote pro-Islamic arguments that denied the “charge that Islam was spread by the sword, and portrayed the Prophet in a uniquely positive light.” Though Stubbe’s book did not find a publisher, Spellberg notes, “it had circulated widely in manuscript form.” Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an is filled with fascinating accounts of polemicists who defended Islam and, more, of liberal democrats in the mold of Jefferson who, despite their individual views of Islam and the Prophet, believed that Muslims should enjoy the full rights of citizenship. Indeed, some of the critical elements of Locke’s views of toleration were developed precisely in his attempt to defend the rights of Muslims—not because he believed in the righteousness of their cause or their religion, but because he believed in the right of liberty and the toleration of others.

In fact, the notions of toleration advocated by Locke and Jefferson are in some ways incompatible with some of the attitudes that Spellberg recommends in her discussion of the question of Muslim civil rights in a liberal democracy today. Spellberg is a professor of history at the University of Texas who received some unwanted attention when, in 2008, she played a role in Random House’s decision not to publish Sherry Jones’s The Jewel of Medina—a racy romance novel about the life of the prophet Mohammad’s young wife A’isha. The reasons that Spellberg offers for her decision to oppose the book’s publication are directly, and ironically, relevant to the subject of her own book, namely the nature of liberal toleration in matters of faith, particularly Islam.

It seems that Random House sent Professor Spellberg galleys of The Jewel of Medina asking for a blurb, since she had published a book on A’isha called Politics, Gender and the Islamic Past: The Legacy of ’A’isha Bint Abi Bakr. Instead, Spellberg wrote a scathing review of the manuscript. It was well within the norms of her academic rights and responsibilities to do so—but she also took the unusual step of warning members of the Muslim community about the possible publication of the book. Before long, Random House, who according to Spellberg had consulted other academics as well, and worried about the possibility of threats, abandoned The Jewel of Medina, which was eventually published by another press.

In explaining why she was opposed to the publication of the book, Spellberg told a Wall Street Journal writer that, while she does not “have a problem with historical fiction,” she does have a “problem with the deliberate misinterpretation of history. You can’t play with sacred history and turn it into soft-core pornography.” Regardless of what one thinks about the strengths and the weaknesses of The Jewel of Medina—I find the book a raunchy and superficial rendition of history: in literary terms it is certainly nothing like The Satanic Verses—it must be said that Jones’s treatment of her theme is, compared with some of the books published in America and Europe in Jefferson’s time, quite tame. Her novel accepts Muhammad as the prophet of God, while most of the books that Jefferson read denied the very existence of a prophetic mission.

Spellberg claimed that in her professional capacity it was her “duty to warn the press of the novel’s potential to provoke anger among some Muslims.” She insisted that people “should read a novel that gets history right.” In other words, there is a “sacred” history—a historian’s sanctity if not a believer’s one—and only novels that respect this “right” and “sacred” history deserve to be read. But surely the notion of a such a sacred, or dogmatically correct, history as a red line that novels—and according to nearly all radical Islamists, scholars—may not cross is the antithesis of Jefferson’s notion of tolerance. Moreover, it opens a Pandora’s box on literary and intellectual life that gives the power of a veto to any of the many sects who claim to have a monopoly on the “real” history.

Spellberg says that in her classes she teaches The Satanic Verses, and we all know what happened to the author of that novel when one claimant to the sacred history found the book blasphemous. And Salman Rushdie was hardly the only victim of such intolerance in recent years: a German scholar—a convert to Islam—was pressured to desist from his research into the historicity of the Prophet’s life; there were controversies surrounding the publication of a Princeton professor’s book about Shiism as a historical construct; an Egyptian scholar was forced into exile for positing that even if we accept the divine source of the Qur’an, we must nevertheless accept that humans can make sense of the holy book only through their own historically determined and contingent consciousness; there was an attempt on the life of Nagib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate, for his temerity in treating the early history of Islam through the metaphors of fiction; there was opposition to the publication of iconoclastic interpretations of the earliest surviving manuscripts of the Qur’an found in the early 1970s on the walls of a mosque in Sana’a, Yemen; and so on.

When Elaine Pagels published her book on the Gnostic Gospels—adding a whole new book to the Scriptural canon—or when Harold Bloom suggested a literary reading of the Book of J and the possibility of its feminine authorship, Christian believers in the sanctity of their Bible were dismayed, but they did not attempt to block their publication. Why must writers, cartoonists, film-makers, and scholars working on Islam be anxious about provoking the fury of some sect in the Muslim community, and even about being physically attacked for their alleged transgression? Spellberg quotes Locke rightly observing that “men in all religions have equally strong persuasions, and every one must judge for himself; nor can anyone judge for another, and you last of all for the magistrate.” No individual or group, in other words, can preemptively decide what is suitable for publication; only the law can settle the question. The more a group or an individual resorts to violence or extra-legal means of intimidation, the more they betray the precepts of a genuine Jeffersonian democracy.

What makes matters even murkier, and potentially perilous, is that there are, as Spellberg herself points out, many “sacred” histories of Islam. Virtually all the schisms in the history of Islam are the results of these conflicting “sacred” histories. The version believed by Wahhabis in Saudi Arabia is considered sacrilege by Shia clerics in Iran; and in Iran, a writer was sent to prison and his paper shut down, and the works of his father—a dead cleric—came under attack for his daring to offer a version of “sacred history” different from official Shia dogma. (The question concerned who should have succeeded the Prophet after his death, and whether such succession was divinely planned. On this issue, the dogmatically approved history in Iran is different from what about three-fifths of the Muslims in the world, that is, the Sunnis, believe.) The fact that more than thirty years ago in Iran an octogenarian senator from the Shah’s period—Ali Dashti, himself a onetime cleric—was sent to the firing squad on the charge of being the author of a pseudonymously published bestselling book about the life of the Prophet—one that partially depended on the findings of German scholars of Islam at the turn of the century—points to the real dangers of Spellberg’s unfortunate surmises about the limits to challenges of “sacred” histories. (When a translation of Dashti’s book was published in English—Twenty Three Years: A Study of the Prophetic Career of Mohammad,translated by F. R. C. Bagley—a professor of Islamic history at Berkeley dismissed the book as having “the stale air of antiquated rationalism” and denounced as “grotesque” the idea of reducing “the prophet [Muhammad] to the status of one of many ‘great men’ of history.”)

If Muslims in the United States are entitled to declare certain parts of the past their sacred history, and thus beyond the reach of fiction or criticism, can Hispanics and Native Americans, Jews and Buddhists, and every other denomination also claim exemptions from critical public scrutiny because their past and their faith is holy to them? Should Mapplethorpe’s art or Buñuel’s films be banned, as they obviously depict images that Christians consider blasphemy? How abut Freud’s Moses and Monotheism? Surely in a liberal democracy, only laws, secular in source and in legitimacy, must govern what is permitted in the public domain, and not the private sensitivities or sanctimonies of any minority (or as Jefferson would argue, even any majority).

The same troubling disposition can be seen in Spellberg’s attitude toward the question of the implementation of sharia law in the United States (and Europe). In trying to expose the dangers of what she rightly deems to be dangerous strains of Islamophobia, she picks easy targets (such as the moronic Michele Bachmann, who “supported the notion that Islamic law is the new great threat to the nation.”) But in so doing, she eschews more serious debates about the nature of law in a liberal democracy. She rightly criticizes the efforts of those who try to “undermine the civil rights and citizenship of all American Muslims.” She rightly chastises those who “contrary to the founding discourse” of the likes of Jefferson define “American identity” as “exclusively Judeo-Christian.” Yet she uses these defensible propositions as a basis to argue that Muslims in America must be allowed to follow sharia law. She writes that “those American Muslims who might follow aspects of Sharia law—and these applications vary widely among believers—do so in their daily prayers, precepts for marriage, divorce, wills, and international commercial transactions.” She tries to put the reader’s mind at ease by suggesting that “these commitments do not remotely amount to a collective effort to seize political power” and “impose Sharia laws on all its citizens.” That is true: we must not be paranoid or prejudiced in this matter. But can a serious student of Locke’s and Jefferson’s ideas on liberal democracy—that it is a country ruled by a common law for everyone arising out of a social contract between the people and the government, where religion belongs to the private domain, and secular, publicly changeable laws are the sole arbiter of the public sphere—seriously believe that by saying that most Muslims do not wish to impose sharia on the rest of the society she has resolved all the philosophical and political anxieties about the question of sharia (or any other religious law) in a liberal democracy? The fact that Islamophobes and jingoists have said coarse and contemptible things about sharia does not mean that the problem is otherwise simple.

It is not clear how Spellberg knows the intentions of those Muslims who want to follow sharia law in the United States. Good laws are never founded on the assumed good intentions of the people. Indeed, they protect the majority and the minority from their darker impulses and programs. More crucially, who is to determine what “aspects” of sharia are to be implemented? As Spellberg herself points out, there are widely different interpretations of sharia. In Iraq, Ayatollah Sistani just decreed that female circumcision is not against sharia. Must American Muslims be allowed to force their daughters to have it? Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran once decreed that nine-year-old girls can be married: should a Shiite father in America be allowed to marry off his nine-year-old? Iranian sharia courts just attempted to pass a law allowing stepfathers to marry their stepdaughters: does this stop at the water’s (or the desert’s) edge? And what if a Muslim decides not to pay income tax, and opts instead to pay his or her religiously required Khoms or Zakat (sharia-mandated taxes)? Sharia law about divorce, custody, abuse, and inheritance invariably disadvantages women. Must a Muslim in America be allowed to divorce his wife in a sharia court? Certainly they should have the liberty to file for divorce in a sharia court, if their religious beliefs dictate it; but the laws on alimony, custody, and community property that determine the legal aspects of the separation must follow the law of the land—and not sharia. The fate of a child in a divorce is a matter of public interest: it cannot be relegated to the private concerns of the members of any religious denomination. Are all these aspects of sharia acceptable in the American context? A Balkanized or multicultural legal system is hardly a remedy for racism or anti-Muslim stereotypes.

The life and works of the prophet Mohammad, no less and no more than the lives of all other prophets and religious leaders, must be regarded historically, in the critical way in which historians regard the past, using all the tools of scholarship. Radical Islamists, with their terror and their threats, and regimes such as the Islamic Republic of Iran, with their fatwas, are trying to impose a reign of silence, if not of terror, to preserve their self-declared “sacred” histories from fair examination. Surely Muslims living in liberal democracies must learn to live and abide by the laws of the land, and must recognize that living in a liberal democracy, as Jefferson said, means that your ultimate arbiter of law is the Constitution, not any sacred text. An assault on one’s faith, or on one’s equality before the law, must be addressed only through legal means—not with threats of violence, or by declarations, by fiat, about the intellectually inviolable sanctity of inherited histories.

Jefferson would have commended Spellberg for unearthing a fascinating moment of American history and for showing how the Founding Fathers defended the rights of a minority that they knew little about. Yet it is no less important to remember that the Founding Fathers, and Jefferson in particular, made no effort to stop the publication of sometimes scurrilous books against not just Muslims, Jews, and Catholics, but also deists, of whom he was arguably one. The Jeffersonian message for our time is not that we should bend to the will of a minority—or a majority—so as to impose or to implement for the entire polity Muslim law or Jewish law or any other religious laws. On the contrary, his message is that any society that wants democracy—whether it has Muslim, Coptic, Jewish, Buddhist, Christian, or (God forbid!) atheist majorities—must limit the realm of religion in public life and relegate all sacred laws to the private realm, and thereby opt instead for a new social contract wherein Jews and Bahá′ís, men and women, gays and lesbians, are equal before the law. Tunisia is the first Muslim country that seems to be moving in that direction. Anything else is un-Jeffersonian.

Abbas Milani is the director of Iranian Studies at Stanford University and the author, most recently, of The Shah (Palgrave Macmillan). He is a contributing editor at The New Republic.