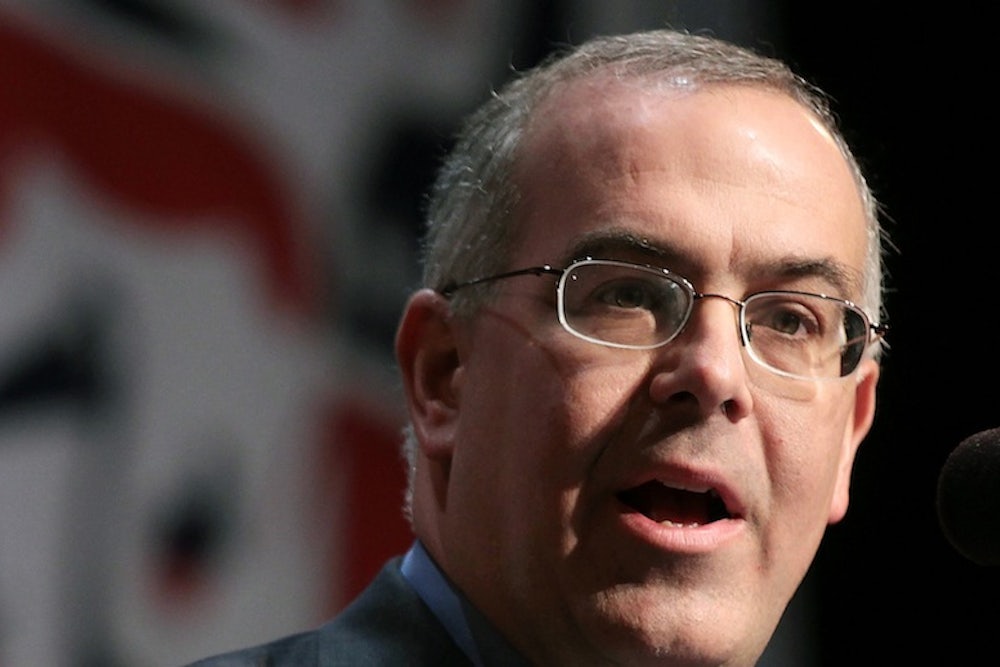

Portentously titled 'The Leaderless Doctrine,' David Brooks's piece today concerns America's shrinking role in the world. After saying that we are in the midst of a "remarkable shift" in how Americans see the country's foreign posture, Brooks gets specific. It isn't, he explains, that we are turning inward culturally or economically. Instead, "Americans have lost faith in the high politics of global affairs. They have lost faith in the idea that American political and military institutions can do much to shape the world. American opinion is marked by an amazing sense of limitation — that there are severe restrictions on what political and military efforts can do."

Already this is a little strained. The first two sentences are matters of opinion, while the third is a simple fact: there are restrictions on what political and military "efforts" can accomplish.

The problem is exacerbated when Brooks explains the reasons for this shift: it isn't just about Iraq or Obama's rhetoric, he argues; no, it is also because people now believe that, "The real power in the world is not military or political. It is the power of individuals to withdraw their consent. In an age of global markets and global media, the power of the state and the tank, it is thought, can pale before the power of the swarms of individuals."

Brooks clearly finds this way of thinking silly, and here is his case:

This is global affairs with the head chopped off...The ensuing doctrine is certainly not Reaganism — the belief that America should use its power to defeat tyranny and promote democracy. It’s not Kantian, or a belief that the world should be governed by international law. It’s not even realism — the belief that diplomats should play elaborate chess games to balance power and advance national interest. It’s a radical belief that the nature of power — where it comes from and how it can be used — has fundamentally shifted, and the people in the big offices just don’t get it.

Essentially, people today have discarded previous doctrines and theories of global affairs, and now believe in what Brooks calls "naïve" and "conflict free" resolution. You might expect, given the picture Brooks has drawn of foolish utopians running wild, that such lunacy and immaturity would have led to a much more dangerous world. Yet surely Brooks knows that by almost any calculation the world is much, much more peaceful than it was during the 20th century, and certainly during his beloved Cold War.

Similarly, for Brooks to write that "Reaganism" was about fighting tyranny and promoting democracy makes him sound like the naïve one. When Ronald Reagan hailed Nicaragua's contras as "the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers," supported dictatorships throughout Africa and Latin America, and even found kind words for the people presiding over apartheid, was he standing up for democracy?

This question becomes even more pertinent when Brooks exclaims that, "It’s frankly naïve to believe that the world’s problems can be conquered through conflict-free cooperation and that the menaces to civilization, whether in the form of Putin or Iran, can be simply not faced." Right. Perhaps we should "face" this vile Iranian regime like Reagan did, which would include making arms deals with it and even sending the current Ayatollah a birthday cake. Then, if we are feeling extra generous about democracy promotion, we could use the proceeds of those arms deals to fund thugs on another continent. No doubt the internet-obsessed youth of today don't have the stomach for such tough policies.