The Internet acts as a powerful echo chamber: Drop a pin and you would think a bomb had gone off. Earlier this month, the bombshell was the news that Mein Kampf had suddenly become a best-selling book. According to reports at Time, ABC News, Fox News, and many other news sites, a 99-cent e-book edition of Hitler’s tract was rocketing up the charts on Amazon and iTunes. Historians and Jewish spokesmen were called on for worried comments; comparisons were made to 50 Shades of Grey. It was enough to make you wonder if, next time you take a peek at someone’s Kindle on the subway, you’ll find them immersed in Hitler’s rants about the Treaty of Versailles.

Look closely at the news reports, however, and it becomes clear that they weren’t actually reporting anything. They were all simply paraphrasing the same essay by Chris Faraone, which originally appeared on the website Vocativ. And Faraone’s evidence for the alleged surge in Mein Kampf sales is, at best, slender. “Kindle Fuhrer: Mein Kampf Tops Amazon Charts,” the headline shouts; but the chart in question turns out to be “Propaganda and Political Psychology,” where Mein Kampf is, as of this writing, number 2. This is a subsection of Amazon’s Politics and Government chart, which in turn is a subsection of the Politics and Social Sciences Chart.

How many actual sales does it take to move up a few notches on a sub-sub-section of Amazon? No one knows, since the ranking algorithm the bookseller uses is secret. But it’s clear that Mein Kampf is fairly deep into the “long tail” section of Amazon’s titles, where a handful of sales could significantly improve its ranking. (The 99-cent Kindle edition of the book is currently ranked 11,855 among all paid e-books.) Are we talking about a hundred downloads? Ten, which just happen to have come in a short period of time? Maybe less?

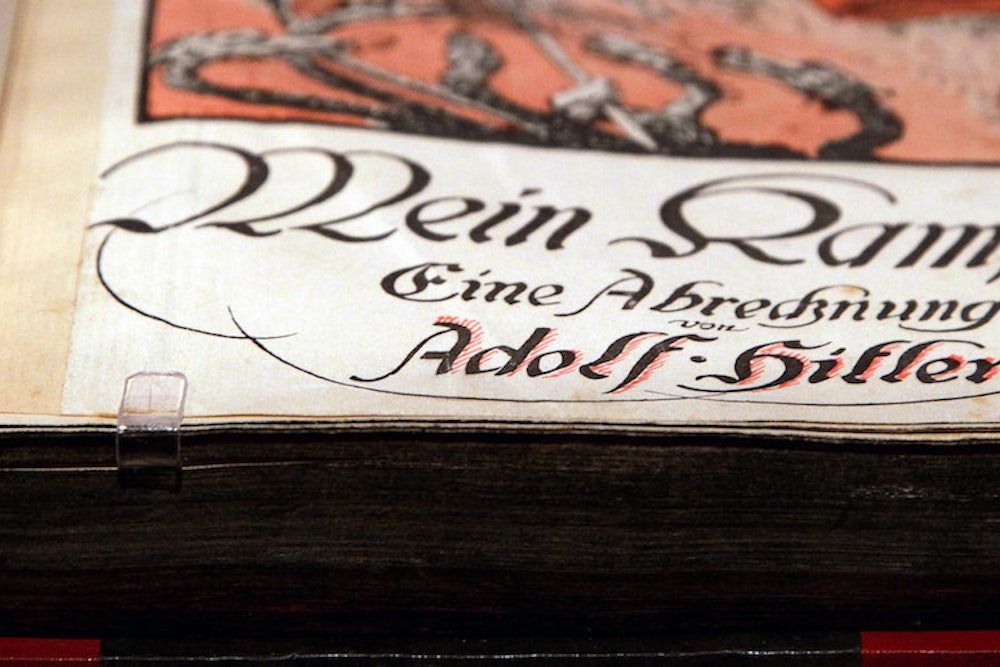

The picture is further complicated by the fact that Mein Kampf is easily available for free online. Neo-nazis can find it on Stormfront, while everyone else can find selections at Jewish Virtual Library; a complete facsimile of the 1941 English edition is hosted at archive.org. Interestingly, that edition, appearing not long before America entered the war against Hitler, lists on its cover not just the author and translator but ten “editorial sponsors.” These literary and academic worthies seemingly had nothing to do with the actual preparation of the book; their names are there strictly to reassure the reader. Even in 1941, the mephitic reputation of Mein Kampf made respectable people feel the need for official permission to pick up a copy.

How many people, then, are reading Mein Kampf in 2014? The answer is that it’s impossible to say, and there’s no real reason to think there are more now than there were six months or six years ago. Yes, the Internet makes it easy to find the book—just as it makes it easy to find hardcore pornography, snuff films, and videos of people eating excrement (remember 2 Girls 1 Cup?). It’s not news that the human imagination is drawn to the forbidden, or that the privacy of the computer screen allows us to violate all kinds of boundaries that remain sacrosanct in real life. Nor should we be surprised that there are people in the world who admire Hitler and hate Jews—after all, they tell us so themselves, all the time. (Just look at the comments section of any of the news reports about Mein Kampf.)

By turning Mein Kampf into a totem of evil, whose very title makes us start jumping at shadows, we only reinforce its dark glamour. At this point in history, no one is going to be converted to Nazism or anti-Semitism by reading Hitler. Indeed, given how execrably written the book is, it’s hard to imagine that many of the people who download Mein Kampf will actually finish it. Owning the book, physically or virtually, is a way of stating one’s politics, not of learning about politics. And since those politics are both hateful and, in the larger scheme of things, utterly marginal, the best thing for us to do with Mein Kampf is to go on ignoring it. Unless, of course, it ever becomes an actual best-seller—in which case we will have a lot worse problems to deal with than literary ones.