Dan Savage is the closest thing the gay community—if that term still registers in our diffuse era—has to an ambassador. Part of the columnist’s prominence can be credited to a certain vacuum: Many out-of-the-closet public figures have avoided becoming poster children for gay rights. (Think of Anderson Cooper’s matter-of-fact coming-out last summer, or Jodie Foster’s tortured Golden Globe speech.) In the meantime, Savage happily and openly crusades against bullying and for marriage equality; he lashes out at conservative pundits and politicians in a stream of blog posts, columns, podcasts, tweets, and media interviews. (I have interviewed him briefly for The New York Observer and Salon.)

In doses, Savage’s writing is exhilarating—he may be viciously angry, jubilant, or poignant. From paragraph to paragraph, one does not know which Savage one will encounter. But between two covers, reading Savage is a jarring experience. Language that seems lively and spirited in column form becomes an argot of righteous rage, self-congratulation, and derision. And as his new collection, American Savage, illustrates, Savage’s apparent strengths can seem like blunt instruments, used so indiscriminately that their impact practically vanishes.

Given that Savage is rightly seen as an original and unafraid advocate for a more progressive, tolerant view of sexuality and relationships, it is surprising to see just how often he’s on the defensive. Even when writing about sex, the subject that brought him to prominence, Savage finds himself responding to his critics as much as he does doling out advice. “I’m frequently told that I overemphasize the importance of sex,” he writes in one essay. “Emily Yoffe, who writes the Dear Prudence column for Slate, doesn’t think very much of my sexual ethics in general or the GGG concept in particular either,” he writes in another (referring to his argument that lovers ought to be “good, giving, and game”).

When Savage does make his case affirmatively—that monogamy ought to, in some cases, be flexible, or that anal sex is not appropriate for a first date, or that a good partner ought to be willing to try new things within reason—he often nears propaganda. He repeats himself endlessly; he cites a Lutheran minister’s praise as proof that he’s right; he refers to himself as “the go-to guy for straight people in need of sex advice” and praises his own “nice dick.” Later in the book, he suggests he may be responsible for the Obama administration’s embrace of the term “Obamacare.” Certainly any book Savage writes would take into account the fact of his fame, but with each mention of a term he’s coined or a controversy he’s caused, American Savage begins to feel like a very public act of self-love.

The book’s most explicitly political writing is its weakest. While Savage has a gift for marshalling facts and trends in service of an argument about human sexuality, he seems at sea writing about electoral politics, like a pundit whose decibel level stands in for finesse. Referring to the John Birch Society, he asks: “[W]ho knew those tinfoil asshats were still meeting?” He’s not wrong that the John Birch Society deserves derision, but this flippancy is characteristic of Savage’s style: take a peripheral group and go after it with venom. Though there are certainly antigay conservative politicians with real power, the Birchers are not among them. Savage also takes onetime presidential contender Herman Cain with a similar mix of revulsion and ironic mockery. “Okay, who remembers Herman Cain? Anyone?” he asks. If Cain is so truly irrelevant, why does Savage devote himself to the man? Is it really worth laying out a “Modest Proposal”-style premise whereby Cain could choose to be gay and service Savage? “Show us how it’s done,” Savage writes. “Suck my dick.” In place of argument, Savage offers insult. Is this any better than the low blows his opponents offer?

The sad irony of such rhetorical technique is that Savage has made Cain (and perhaps others) into a more substantive public figure in the act of lambasting him. No one was hungering for a Cain takedown. Many readers likely needed to be reminded who he was. But this doesn’t matter to Savage—he lends Cain, along with former presidential candidate Mike Huckabee, and other leaders of the sort of antigay groups (like the Family Research Council) that lost resoundingly in 2012, a power they do not deserve. But perhaps more importantly, this means that Savage’s argument for marriage equality is entirely reactive, established according to the terms that disempowered Republicans have deployed. (At least he adds a few curse words for that classic Savage frisson.)

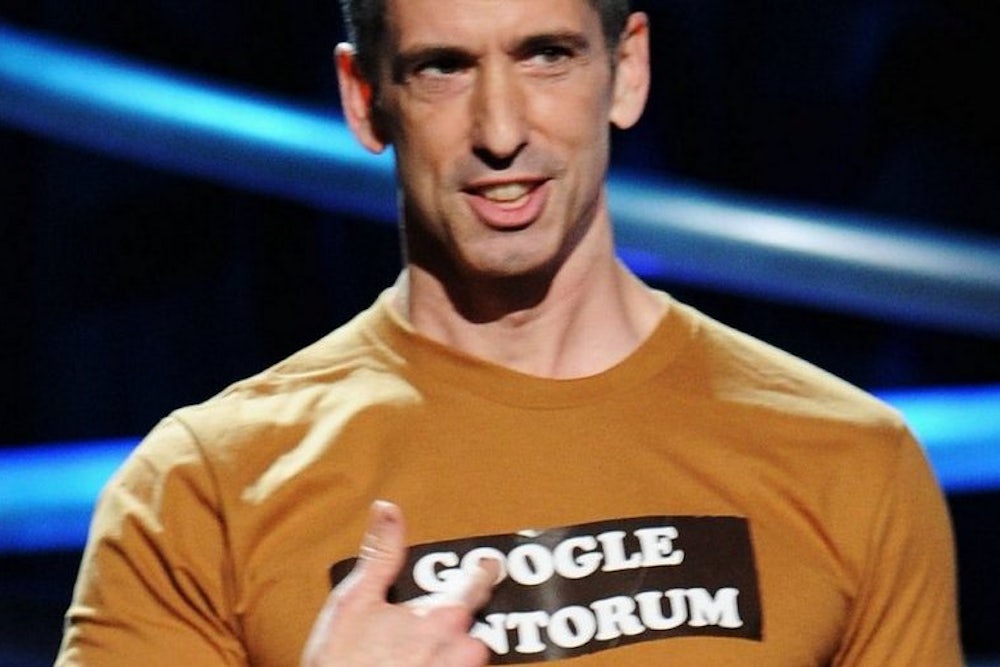

There is some satisfaction here for a reader sympathetic to Savage’s position. But it has less to do with Savage’s arguments than the march of history. In 2003, Santorum’s comparison of homosexual intercourse to “man on child, man on dog” was, if not mainstream, a revulsion many shared. Savage’s campaign to tie Google results for “Santorum” to a graphic bodily emission was effective as a way of demonstrating that gay people simply weren’t going to accept exclusion. It was a bright spot in a dark time. But history has moved faster than anyone might have predicted, and Savage’s condemnations now seem, finally, thankfully, pointless. He’s not taking on sitting U.S. senators; he’s taking on former politicians and political activists whose power is subsiding or practically gone. He may well have had much to do with the degree to which the Rick Santorums of the world fell from power (though, as Savage notes, Santorum did well in the 2012 Republican primaries), but changing times necessitate changing rhetoric.

The nadir of American Savage comes when Savage prints a one-act play called Jesus and the Huge Asshole, about religious objectors to Obamacare. It was occasioned by a Philadelphia sandwich-shop owner who suggested he would need to raise prices due to the health-care law, an event even the most ardent Obamacare partisan will probably think of as a footnote to history. In the play, Jesus lists various Christian teachings, then asks: “[D]oes any of this shit ring a bell? Any of it, you stupid asshole?” One has cause to wonder if one person who didn’t already support Savage’s own causes could possibly be convinced by his scorn.

He does try, though: His book’s conclusion considers a recent event at which Savage debated Brian Brown, an equally inflammatory opponent of gay marriage, and broadcast the event online. Engaging the opposition represents a step forward for a man who once referred to religious objectors to gay marriage as “pansy ass[es].” And yet Savage declares that the winner of the debate is his husband, who cursed at Brown and ejected him from the house post-debate after Brown (predictably) implied Savage should not be a parent. Brown’s beliefs do and should strike a growing majority of the American people as risible. But if Savage believes exclusion and profanity win out, he’s learned the wrong lessons from his opponents.