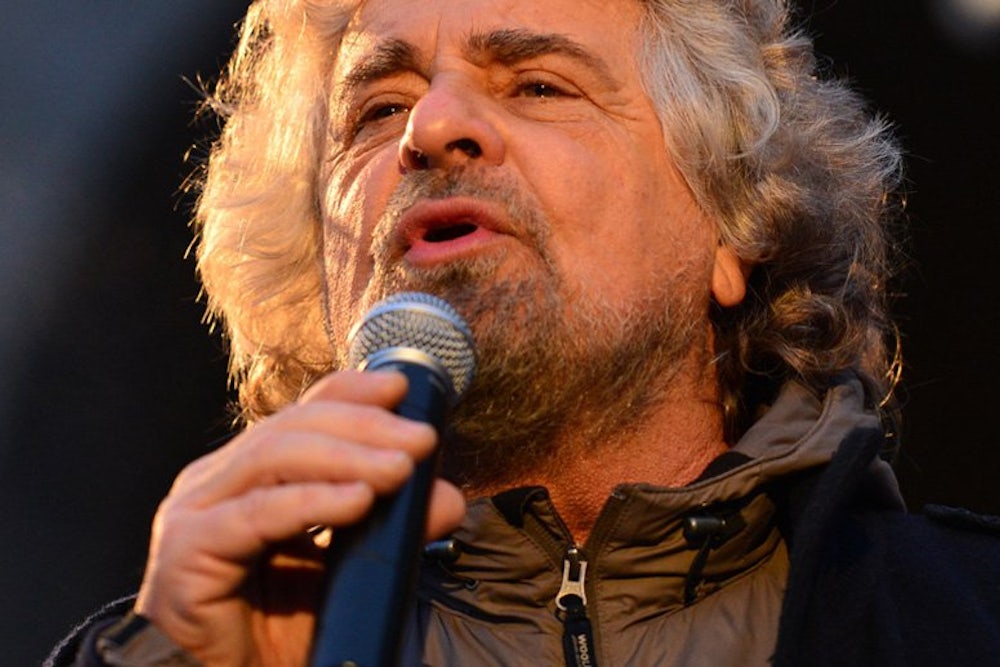

“Something is happening and you don’t know what it is. Do you, Mr. Jones?” Bob Dylan sang. Mr. Jones was the typical suburban “square,” and the “something” that was happening was the sudden explosion of the new left and the counter-culture during the Sixties. Something extraordinary is happening now in European and American politics. It is epitomized by the recent Italian elections, where a new party, the Five Star Movement, led by a comedian, Beppe Grillo, got over a quarter of the vote, denying a governing majority to either the center-right or enter-left parties.

Similar new parties have been shaking up conventional politics in Europe over the last decade. They include Denmark’s Peoples’ Party, Netherland’s Freedom Party, France’s Front National, Italy’s Northern League, and Greece’s Syriza Party. In the United States, where the political system discourages new parties, the same ferment can be found in the Tea Parties and in the Occupation movements.

One thing that currently unites almost all the groups—and you would have to throw in Germany’s Pirates here—is the use of social media as the principal means of mobilizing support. As the British research group Demos recounts in a new report, the rise of Grillo’s party was based on his web site and blog. With social media as its foundation, the party used techniques like the meet-ups pioneered by Moveon.org to mobilize in towns and cities. Social media allowed the Five Star Movement and other groups to bypass the big-money requirements of television-based party politics or the union-based politics of the traditional left.

But the rise of these groups is rooted in widespread dissatisfaction with the parties in power. Initially, many of the European groups like Denmark’s People’s Party, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party, or Italy’s Northern League arose in opposition to tolerant policies toward immigration into the European Union. After September 11, they were particularly opposed to immigration from Muslim countries. But most of these groups had a working class base and were leftwing in their economic outlook. They opposed social spending cuts and were concerned about globalization’s effect on wages and jobs. Since the onset of the Great Recession, and EU’s final crisis, some of the new groups have focused on economics and political corruption.

Greece’s Syriza was a coalition of leftwing groups led by a former Communist Alexis Syrpis. In the 2012 election, it came in a close second to the Center-Right party and marginalized Pasok, the older socialist party. Syriza advocated the abrogation of the austerity measures that EU imposed upon Greece. These measures have led to 25 percent unemployment, a 30 percent drop in private sector wages, and the reduction by a quarter from 2009 of Greece’s gross domestic product (GDP). Syriza didn’t advocate leaving the Eurozone, but threatened to do so if the EU and the Germans, the EU’s strongest economy, were not willing to renegotiate the terms of Greece’s bailout. Syriza remains the principal opposition party in the Greek parliament.

Grillo founded the Five Star Movement—the five stars stand for different policy areas (ie: the environment, access to the internet)—in October 2009 and the party remains under his control. Its members are drawn primarily, but not exclusively, from left of center voters. Its platform includes strong planks on environmental protection and climate change, universal health insurance, public access to the internet, and political reform. In his statements, Grillo, who does not run for office, has attacked the government’s austerity measures, which were taken to win support from the EU and its central bank. He has said he thinks that “Italy cannot afford the luxury of being in the Euro,” and he advocates a public referendum to decide whether to remain to the Eurozone. Like Greece, Italy has suffered under the EU-imposed austerity. Its unemployment rate is now 11.6 percent and unemployment among youth is 36 percent.

In the United States, the counterparts of these groups are the Tea Parties and the Occupation movement. If the United States had a multi-party system like Italy, the Tea Party might have won 30 percent of the vote in 2010 and would have done pretty well in 2012 as well. These groups, like Syriza and the Five Star Movement, arose in the wake of the Great Recession. While the Tea Parties, like Europe’s anti-immigrant parties, looked primarily down the class ladder for villains, the Occupation movement very much came out of a left disillusioned with Barack Obama’s embrace in the summer of 2011 of a politics of austerity. Both movements have dimmed, but could easily regain their luster if the downturn in the American economy persists.

Third parties, and in this case fourth or fifth parties, and opposition movements are usually just nuisances to the major parties. Ross Perot didn’t really cost George H. W. Bush the election, and it’s also a stretch—given the corruption of the Florida vote and the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore—to blame Ralph Nader’s candidacy for the 2000 result. In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen and the Front National came in second, eliminating the Socialists from the run-off, but the Front National did not play a major role in the last two French presidential elections. The recent assortment of parties and groups has had, however, a far more disruptive effect on European politics; and in the U.S., the rise of the Tea Party helped push the Republican party farther to the right. By doing this, the Tea Party contributed to the American version of Europe’s political disorder—the current gridlock in Congress.

The rise of social media has contributed to the power of these groups to disrupt normal politics, but the other factor—which ties together Syriza and the Five Star Movement with the Tea Parties and Occupation movements—is that they reflect the inability to date of the major parties to deal with the global economic downturn. In Europe, the fault lies partly with benighted public officials who have embraced a pre-Keynesian economics of austerity, but also with the common currency.

Before the euro was installed in 2002 as the continent’s currency, Italy responded to trade deficits with Germany or other countries by devaluing its currency, which made their imports more expensive and its exports cheaper. But it could not do so under the common currency. And Germany, which has benefitted from no longer having the relatively strong deutschmark, has been unwilling to back measures that would seriously alleviate austerity in Italy, Spain, and Greece. The traditional leftwing parties in these countries have buckled to Germany and Europe’s central bankers, but their populations, which have to endure Great Depression-like hardship, have bristled, and have backed militant opposition groups like Syriza and the Five Star Movement. That opposition will continue as long as these countries fail to find relief and might eventually lead to the breakup of the Euro bloc.

In the United States, the situation is different. The Tea Party’s role has been, in effect, to reinforce the conditions that led to its emergence. By pressing for an American politics of public austerity—most recently by cheering on the sequester—these rightwing opposition groups prolong the downturn. After the rise of the Occupation movement in the fall of 2011, a chastened Obama adopted much of its rhetoric on inequality and austerity, but if he should fail to break the budgetary deadlock in Congress, and if the economy still staggers along under the burden of unnecessary budget cuts, the Occupation movement, or some aptly-named successor, is likely to take the stage and like Grillo’s Five Star Movement, use the power of the social media to agitate for an end to self-induced austerity.

The important thing to recognize about these movements is that while they are unruly, and are led by an assortment of former communists, comedians and aging hippies, they display a better grasp of economics than the bankers and politicians—the Mr. Joneses of this era—who dominate leading institutions and major parties. As Paul Krugman has repeatedly pointed out, Europe’s austerity measures and America’s budget cuts have not hastened but delayed a recovery and in countries like Greece, Italy and Spain are creating depression-like conditions. Dissident parties like Italy’s Five Star Movement portend political disorder, but could also force Europe and the United States to embrace an economics that actually works.